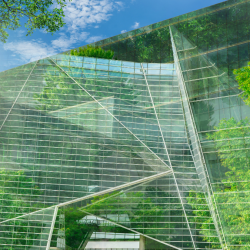

When I was in school through the 1990s, ‘reduce, reuse, recycle,’ was something of a mantra taught to us in class

It was one of a myriad of ways in which my classmates and I were being made aware of our responsibility to the environment, of our obligation to eventually become good citizens. ‘Reduce, reuse, recycle’ offered a concrete, simple, step-by-step approach to making a difference and making the world a better place — something adults tended to teach children about, without necessarily applying themselves to the same task. As it turns out, my sense of this being a mantra was prescient.

Like most mantras, ‘reduce, reuse, recycle’ felt like the right thing to say and the virtuous thing to occasionally act on. It also conveniently faded away into the background as undergraduate studies, pocket money and consumerism began to beckon. Figuring out style and self-expression as I shopped was fun. And in any case, the ozone layer was healing and we were all getting more informed about where to dispose of our trash and how to segregate it. ‘Reduce, reuse, recycle’ soon became a quaint line that I’d notice next to printers and photocopying machines in colleges and at the offices I’d visit for job interviews.

By the time my pay checks had begun to add a little heft to my identity and role as a consumer, something else was in the air — sustainability.

What this term lacked in sturdiness and simplicity, it made up for with a cosmopolitan breadth, even sophistication.

Sustainability was primarily concerned with the impact of goods and services on the environment

But it was so much more than that. The term encompassed notions of sourcing, manufacturing and supply chains and meshed them with values, ethics and social justice. It wasn’t enough to think about what was being made, how and most importantly, in what quantities. One also had to think in terms of equitability — who was doing the making, and under what circumstances? These ideas soon started shading into soft focus notions of quality and inevitably, prestige. Were your coffee beans not just fair-trade, but organically farmed and harvested? Was it enough for your beauty products to be sold to you in a recyclable jar? Shouldn’t they also be clean and espouse the same values as you?

Profoundly important and often distinct issues became bundled into a catch-all term. It was difficult to object — all of these considerations matter. But without specificity, words lose meaning. Sustainability as deployed by brands and businesses today is often inherently and even deliberately confusing.

Experts publish articles encouraging luxury brands to position themselves as sustainable on the basis of their commitment to local craftsmanship. Admirable as this might be, one wonders what it has to do with issues of climate change, and a balance between resources extracted from and invested into the land.

I shop in less rarefied realms

But I’ve found myself increasingly bewildered about what the sustainable choice might be. Bolstered by a belief in the superiority of cotton versus plastic, I liked the idea of tote bags. I enjoyed their shapes and textures, the creative canvas they provided for brands I patronize. So I began to collect them. It was only in June this year that I realized my fixation came with steep costs attached — apparently, a single cotton tote bag has to be used 20,000 times to offset its production impact.

Reader, I own over 20 totes. I haven’t bought a tote bag since, but it’s only been a couple of months. And it would be dishonest of me to say that there isn’t a little undercurrent of resentment running under this self-imposed ban — if cotton is resource-intensive, but plastic is worse, where do I take my desire for some harmless store-bought indulgence? Why didn’t anyone warn me before I got attached?

The beauty of ‘reduce, reuse, recycle’ was that it forced us to consider the question of less, and more. There was no getting around it — reduce means cutting back, or at least trying to. In an age where decluttering gurus now have merchandise lines, no wonder this phrase has fallen terribly out of fashion.

Sustainability is an alluring idea

Noble and admirable — and elusive. Thinking in terms of sustainability allows us to sidestep the question of just how much we already have. We’re allowed to accumulate more and more objects of desire, so long as they conform to a broad set of parameters. A product might not fit all your criteria, but so long as it meets several – and you pay a hefty premium for the privilege — surely you’ve done more good than harm?

The truth is that there’s no shopping our way to sustainability, to a perfect balance between our desires as consumers, an equitable distribution of wealth, and a literal, corporeal enrichment of the planet. The idea of sustainability might have once been incredibly powerful. But looked at closely, it allows manufacturers to make ‘quality’ less affordable, to diversify product lines, and to bring us back to stores and websites in our search for things that will bring us delight and relief in equal measure.

Sustainability isn’t exactly a scam, but it does feel like a maze we’ve been wandering around for far too long.

Featured image: Asli Merve / Pexels