One of the most eye-opening books of the last few years is Factfulness. This 2018 bestseller was by the Swedish data scientist Hans Rosling and compares how our perceptions of the world differ from the reality.

At the heart of his work is a survey he sent to 12,000 people in 14 countries. To give you an idea of the questions, I’ve included a couple below.

Grab a pen and paper and note down your best guess to each of them.

Here goes:

- In the last 20 years, the proportion of the world population living in extreme poverty has…

a. Almost doubled

b. Remained more or less the same

c. Almost halved - What is the life expectancy of the world today?

a. 50 years

b. 60 years

c. 70 years - How did the number of deaths per year from natural disasters change over the last hundred years?

a. More than doubled

b. Remained about the same

c. Decreased to less than half

Rosling asked his participants these questions, along with another nine.

When he tallied the results, he found the answers were way out: on average people got just two right. That’s not merely bad, it’s significantly less than chance. As Rosling says, a trained chimpanzee would have done better.

But people weren’t just wrong, their answers were systematically wrong. In his words: “The human errors tend to be in one direction. Every group of people I ask thinks the world is more frightening, more violent, and more hopeless – in short more dramatic – than it really is.”

Rosling argues that part of the reason is that negative news is more memorable than positive. His assertion is supported by a large body of evidence from psychologists. For example, in 1991 Felicia Pratto, an academic at Berkeley, asked people to read a list of 40 personality traits: half positive and half negative. Later, she asked them to recall as many of the traits as possible. She found they were twice as likely to recall the negative words as the positive ones.

There’s an evolutionary argument for this bias. Think about our ancestors. Survival depended more on remembering bad events rather than good ones. Recalling which berries made them feel ill or which watering hole was infested with predators was a life and death matter. Remembering what made them happy was a luxury.

Little justification for gloomy perceptions

This negativity bias doesn’t just affect the public, it affects professionals too. And it’s alive and kicking in marketing today.

Think about the headlines and opinion pieces in the trade press. Whether it’s the death of TV, declining attention spans or the trust crisis, there’s often an apocalyptic bent to them.

But if you investigate the problem, there’s normally little justification for the degree of gloom.

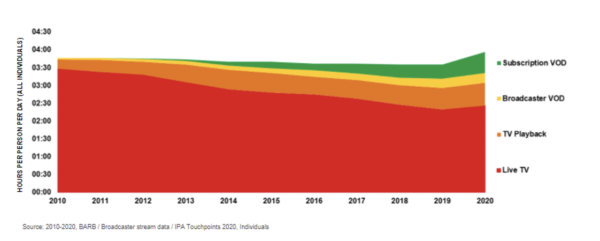

Consider the stories about the death of TV. They paint a dystopian picture that isn’t accurate: the reality is more nuanced. Have a look at the chart below, which shows average daily hours of TV watched in the UK. (The chart is from Thinkbox but the data is from BARB & IPA Touchpoints).

It’s certainly true that time spent watching live TV has declined over the last 10 years. But that’s been more than offset by the amount of video on demand we’re watching. There’s nothing in the data that justifies the hyperbole about the medium’s imminent death.

Or think about the supposed trust crisis. That’s another staple story in the trade press. Supposedly consumers’ trust in businesses and brands is lower now than ever.

That’s certainly the popular perception among marketers. I surveyed nearly 500 marketers about whether they thought that brands were more or less trusted than 20 years ago. The results were conclusive: 72% believed things had got worse over that time period, compared to only 17% thinking the situation had improved.

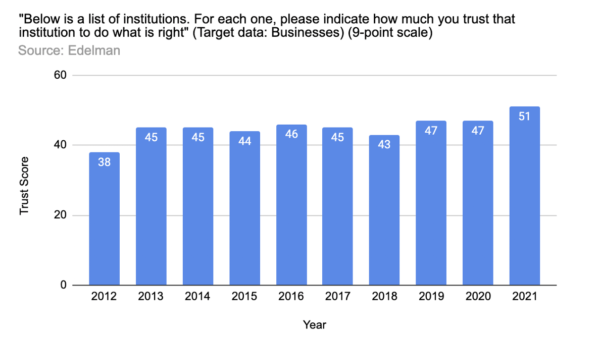

But again, there’s little evidence for this pessimism. Each year Edelman releases data on trust in business in the UK. I trawled through it all the way back to 2012, which was the oldest data I could find. You can see it charted up below.

The 2021 trust figure is the highest on record: 13 percentage points higher than it was in 2012.

Once again, the facts are more nuanced than the perception. Trust in business might be low, with roughly half the population not trusting business, but it has always been low. That’s evidence of a long-term problem, rather than a one-off crisis.

But does this negativity bias in marketing matter?

I think it does. If marketers believe TV is dead, they’ll misallocate their media budget.

If marketers think we’re in a trust crisis, it means they believe we’re in unprecedented times. That sense of uniqueness might cause them to disregard the historic tactics that brands have used to boost their trust through the ages. After all, why look back at past case histories if those brands faced a different problem?

In each case, if our perception differs from reality, we’ll make suboptimal decisions.

So, next time you hear dramatic claims of a marketing dystopia, remember the negativity bias and that things aren’t probably as bad as they seem.

Oh, and, in case you’re wondering. The answers to the questions I posed at the beginning are: 1) C, 2) C, and 3) C. In every case, the most positive answer is the correct one.

It’s not just in marketing that reality differs from overly gloomy perceptions.

Astroten’s next workshop on applying behavioural science to marketing is in March. Update: this event is now sold out, but keep an eye out for future workshops.

Featured image: The Matrix (1999)