William Bernbach, one of the twentieth century’s greatest advertisers, famously said: ‘Advertising is fundamentally persuasion’. The thinking around persuasion has changed in recent decades: Bernbach called it ‘an art’, whereas behavioural economists and psychologists now see persuasion as a science. But Bernbach’s insight holds. Strip away the focus groups, data analytics, and semiotic insights, and advertising and branding aim above all to persuade the audience — whether to buy a product or buy into an idea.

Political marketing is no different. All election campaigning — the rallies, the billboards, the leaflets, the party political broadcasts, the televised debates and the social media hysteria — is designed to persuade voters to believe and, ultimately, to back a party at the polls. Time magazine has proclaimed 2024 ‘The Ultimate Election Year’, with nearly half the world’s population due to vote in national polls, including the United States presidential election (4 November) and the UK General Election (4 July).

So, what can brands and advertisers learn from the persuasive force of political marketing?

The best place to begin is where politics and advertising overlap. Indeed, the most famous piece of political marketing in British history also happens to be one of the most celebrated works of advertising and copywriting. Saatchi & Saatchi’s famous ‘Labour isn’t working’ poster, featuring a snaking ‘dole queue’ (staged, of course, by Conservative Party members) has been credited with helping to ‘propel Margaret Thatcher to power’. Kevin Chesters has recently pointed out that the stunt was not quite the all-conquering force marketers have assumed. Nevertheless, in 1999 Campaign proclaimed it the ‘Best Poster of the Century’, and its influence among politicians and advertisers remains undimmed. Using a single memorable image with a punning, three-word slogan (meaning ‘the Labour party isn’t doing a good job’ and ‘unemployment is out of control under Labour’), the Saatchi poster set the standard for persuasive advertising, political or otherwise, combining visual and textual simplicity with a clear and powerful message.

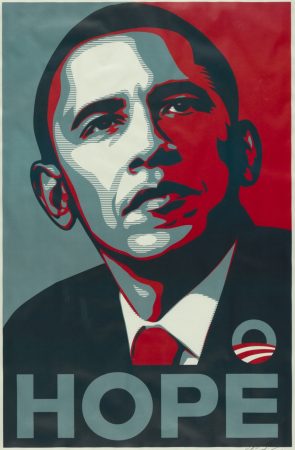

Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign also made shrewd use of slogans, iconography and the fundamental advertising principle of leading with emotional benefits over rational features.

Shepard Fairey’s famous ‘Hope’ poster (along with its ‘Change’ and ‘Progress’ variations) riffed on John F. Kennedy’s 1961 White House portrait, using a two-tone colour scheme that suggested a middle ground between Republican and Democratic political ideals. During the campaign, Obama also adopted ‘Yes We Can’ as his verbal leitmotif — that is, after his wife Michelle convinced him it wasn’t too ‘corny’.

The slogan resounded loudly in Obama’s stump speeches and primary addresses before eventually recurring seven times as the triumphant refrain of his victory speech. This kind of simple, optimistic messaging, delivered in the earthy monosyllables of the Anglo-Saxon register, can be recruited to create powerful, persuasive and emotionally effective marketing. For instance, Nike’s celebrated ‘Just Do It’ campaigns, the first of which was created in 1987 by Wieden + Kennedy, work in the same way as Obama’s ‘Yes We Can’. Both persuade audiences to take action using straightforward, memorable language and inspiring imagery.

Of course, political marketing doesn’t always need to be clear and precise to persuade. ‘Make America Great Again’, the strapline refashioned for Donald Trump’s successful 2016 presidential campaign using Ronald Regan’s winning 1980 slogan, is so vague as to be virtually meaningless (see also: ‘Let’s take back control’ and ‘Brexit means Brexit’). But as an emotional appeal, a rallying cry, and a slogan of solidarity, ‘Make America Great Again’ was astonishingly persuasive, helping political outsider Trump shock the world by defeating the favoured Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton. Evoking the idealised past or ‘golden age’ as a benchmark for a utopian future has been a mainstay of political persuasion for millennia, from Ancient Greek political thought to Boris Johnson’s ill-starred remark to the House of Commons – scarcely believable now – that his election as UK prime minister in July 2019 marked the ‘beginning of a new golden age’.

Brands can also harness the persuasive power of hazy utopian projection in their campaigns. For instance, Audi’s ‘Vorsprung durch Technik’ (‘Progress through Technology’) enjoyed instant and long-term success, embedding the carmaker’s prized German heritage into the British public consciousness. The tagline promised a better future through engineering expertise, and thus tapped into the excitement and uncertainty accompanying the wave of new technologies and rapid industrial change that characterised the sci-fi and futurist popular culture of the 1980s, expressed in films like Star Wars, Blade Runner, Tron and Back to the Future.

As well as utopian sloganeering, politicians frequently turn to originality and novelty as campaign themes. In 1994, and approaching two decades out of power, the Labour Party in Britain was remade and rebranded as ‘New Labour’ by incoming leader Tony Blair. The idea was simple but persuasive, helping to banish the image of ‘Old Labour’ and persuade the UK electorate that the party stood for innovation, progress and national renewal, embodied in the slogan ‘New Labour, New Britain’ — contrasted, of course, with the ‘Same old Tories’. In 1997, Blair led his party to a landslide victory, including persuading 10% of the electorate to switch their vote to Labour.

The very same year Apple launched its ‘Think Different’ campaign. The aim was to associate the company with the innovation and imagination of cultural pioneers like Pablo Picasso, Bob Dylan, and Rosa Parks, to set the brand apart as ‘innovating’ and ‘breaking new ground’. Once again, like the most persuasive political messaging, ‘Think Different’ was uncomplicated and unforgettable — a testament to the success of Steve Jobs’ ‘obsession’ with simplicity, as Apple’s creative director Ken Segall explains in his 2012 book Insanely Simple: The Obsession That Drives Apple’s Success. Like New Labour, Apple sought to position itself as a creative genius at the vanguard of technology and culture — and their rivals as backwards and outdated. ‘Think Different’ directly challenged the-then dominant computer manufacturer by riffing on IBM’s slogan ‘THINK’. Just as New Labour persuaded the British public that Blair offered a fresh, new alternative to the status quo, Apple convinced consumers that true, trailblazing innovation lay with them.

The ‘Year of Elections’ presents a unique opportunity to witness the full force — and the dark arts — of political campaigning across every media channel and platform. Brands, marketers and advertisers should pay close attention to the campaigns that win the battle to persuade the voting public in 2024.

Featured image: Polina Zimmerman / Pexels