The notion of leaving a legacy can be an intoxicating concept. Because one of the biggest existential stresses we grapple with is this idea that no-one will remember us when we are gone.

And if they don’t, what is my purpose?

Hang on, is my life pointless?

Oh god, what the hell am I doing here?

And on it spirals into the abyss, until the alarm sounds another day.

Leaving an imprint or impact visible to future generations can therefore be seen as a failsafe way of keeping a part of us alive.

Ironically, as we age, we get better with dealing with the prospect of dying. Time magazine reported a large meta-analysis study which found that fear of death grows in the first half of life, but by the time we hit our sixties, it recedes to a manageable level.

But still, often, thoughts of a legacy linger…

This notion is, however, mostly folly. Shelley’s great poem Ozymandias demonstrates this with the tale of a Roman historian discovering a ruined statue in the desert bearing the words; My name is Ozymandias, King of Kings; Look on my Works, ye Mighty, and despair!

I guess, ironically, Shelley’s poem about the futile nature of legacy is part of his legacy, but let’s not get too meta here. We’ll just say, it is very likely you will not be remembered much after your children/grandchildren are gone. And with 45% of women expected to be childless by 2030, that’s if you even have kids.

But that’s okay.

I’d argue that thinking too much about the legacy you want to leave behind in the future is distracting you from the now. And, even if you’re not the type prone to meditation or sound baths, being able to live in the moment is crucial to a sense of wellbeing.

This is no better demonstrated than by Japanese elders in Okinawa, who are famed for being amongst the longest living in the world. The reason is put down to their practice of Ikigai. Iki means life, and gai, is worth. In essence, Ikigai is what gets you out of bed in the morning.

Consultancies and training companies alike have seized on the concept of Ikigai often turning it into little more than a framework to help determine brand purpose. But the concept is both smaller — and bigger — than purpose itself. Hasegawa, a psychologist researching Ikigai says, ‘In Japan we have jinsei, which means lifetime and seikatsu, which means everyday life. The concept of ikigai aligns more to latter. Japanese people believe that the sum of small joys in everyday life results in a more fulfilling life as a whole.‘

In short, what gets you out of bed in the morning, what brings you every-day joy is what keeps you feeling — and perhaps indeed being — alive.

With the current living situation in the UK it feels like we certainly all need a bit of this in our lives. And it presents an opportunity for marketers and brands to connect with consumers in a more meaningful — and useful way. Our recent Wavemaker cost-of-living research revealed a drop in consumers wanting brands to actively help them manage the crisis, talk to them about finance or give them tips and tricks. This is not because the issues have gone, rather that fatigue has set in. Rather than role for brands being to solve the big problems, or teach the world to sing, perhaps it’s time to espouse the Ikigai concept of the sum of small joys.

In our industry, brands talk a lot about ‘joy’. Perhaps too much. Cadbury spent many years instructing us to Free the Joy, Boots insists on Joy for All, and Aperol asserts that, Together we Joy (who knew it was a verb!). But these mostly feel like higher purpose concepts, out of reach to consumers.

One well-known exception is IKEA’s The Wonderful Everyday. Recognised as one of the most effective and enduring UK campaigns it’s evolved from the Simple Joy of Storage to more expansive iterations such The Wonderful Life. IKEA’s Laurent Tiersen described this as ‘the Wonderful Everyday through the eyes of someone who’s lived a long, fulfilling life, made up of the small personal moments that add wonder to our everyday.’

Yes, Yes, Ikea is Swedish as meatballs and loganberries, but the concept itself sounds very much Ikigai, doesn’t it?

Perhaps our view of what legacy is needs to shift. As Leonardo Da Vinci said:

‘As a well-spent day brings happy sleep, so a life well spent brings happy death.’

Perhaps if we stopped fretting about what happens after we die, and as marketers, helped people enjoy the small joys instead, we could all be more than the sum of our parts.

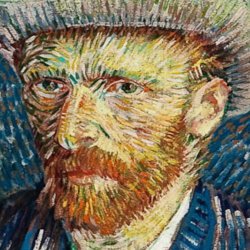

Featured image: Toru YAMANAKATORU YAMANAKA/AFP / Getty Images