Have you ever wondered why bad impressions linger longer than good, criticism cuts deeper than praise and why negative news gets more attention than good news?

That’s our negativity bias. Humans are hardwired to pay more attention to the bad stuff. In the current climate, it feels like the power of bad is supersized. But by understanding the negativity bias instead of ignoring it — or worse, trying to fight it — we can put it to good use. Politicians know it. Publishers know it. Hollywood knows it. Brands have long ignored its power, but the truth is it’s time to wield its power, for good.

1. Be radically honest

This might sound counter-intuitive, but a ‘flaws and all’ approach can help capture attention and build trust and make brands more alluring. Instead of reaching for perfection to build desire, what we actually need is a little less aspiration and a little more realism. Because in times of turmoil, too much positivity is simply untrustworthy. In the age of authenticity, brands no longer need to sell the dream: they need to sell the truth. When our audience is grappling with inevitable truths like the climate crisis and racial injustice: relentless positivity becomes disingenuous.

2. Use the bad to mobilise the good

Bad moments are rubbish, granted. But often it’s these low moments that propel us forward and become catalysts for progress. They inspire us to make the positive change we want to see in the world. Bad is a powerful motivator. And failures, though undeniably sh*t, are important lessons. If we choose to harness that negative energy and carry with us past learnings, we can create better alternatives, instead of just sweeping those difficult feelings under the rug.

3. Create chaotic experiences

If there’s anything as hardwired as the negativity bias, it’s the belief that consumers are hungry for positive experiences. Right? Wrong. The reality is that sticky brands defy all the normal rules by actually making people unhappy. Think about it: unpredictable games keep us predictably engrossed, dating apps keep users hooked on the hunt and the pain you experience in sport only makes success taste sweeter. We’re all addicted to the good-then-bad-then-good-again cycle. So embrace the chaos.

4. Wield the seductive power of bad

Brands are obsessed with looking good. Yawn. Goodness may be admirable, but it’s bland as hell. It’s bad we find sexy. That’s why popular culture is obsessed with baddies. Whether it’s vampires or villains, serial killers or zombies — evil is irresistible (or rather, goodness is boring). Baddies live freely, unconstrained by societal expectations — indulging the urges that us goodies repress.

Let’s face it, a rebel mindset has never been more vital: it releases us from archaic taboos and forgoes the rules that no longer serve us.

The negativity bias cannot be magically eliminated, but neither should it make us slaves to the doom scroll. By embracing its power, we can wield it for good.

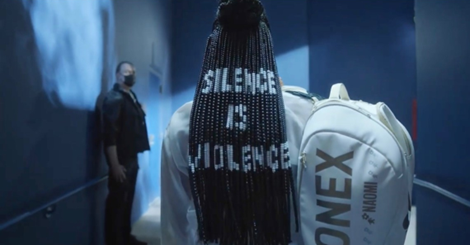

Featured image: Dr. Martens connects with the rebels and non-conformists