From the things we consume to our ways of life, is anything fit for purpose anymore? Are humans actually doing anything right? Do we need a radical rethink of everything? And is that even possible, or is effective change only ever incremental?

Well, let’s begin with this question: are humans doing anything right? I want to start here, because the idea that everything is going to shit seems pervasive. And this potentially leads to a destructive sense of fatalism.

Tune in to the news, and the notion that we’re all going to hell in a handcart is understandable. Pandemics, economic crises, war and the shadow of nuclear disaster, and the destruction of our natural environment — set against a backdrop of lies and short-termist thinking from our so-called leaders. It all sounds pretty grim.

But… BUT. Are we focusing on all the negatives and neglecting the positives?

Let’s not forget that news is big business. And to sell stories, the media successfully taps into some pretty powerful biases.

Let’s take a look at the evidence for these.

Bad news sells

We are naturally drawn to bad news stories — the media would be foolish not to supply them to us.

An example of the evidence for this negativity bias comes from a 2019 study by Stuart Soroka from the University of California. He investigated whether demand for negative information is as prevalent as assumed, and if it’s globally consistent.

The study included participants from 17 countries, across six continents. Respondents watched seven randomly ordered BBC World News stories. Sometimes the stories were positive (e.g. a young child recovering from liver disease), other times negative (e.g. UN investigations into war crimes in Sri Lanka).

While watching the stories, participants wore sensors on their fingers to capture skin conductance and blood volume pulse. Across respondents, Soroka found that negative news provoked stronger physiological reactions and garnered more attention than positive or neutral news on average.

In another study in 1998, Tiffany Ito and her colleagues from Ohio State University showed participants various images, which were either neutral (e.g. a plate, an electric outlet), positive (e.g. people enjoying themselves) or negative (e.g. a gun pointed at an individual).

The researchers then measured participants’ brain activity. They found that individuals’ brains responded much more intensively to negative stimuli, in comparison to positive stimuli, and even more so compared to neutral stimuli.

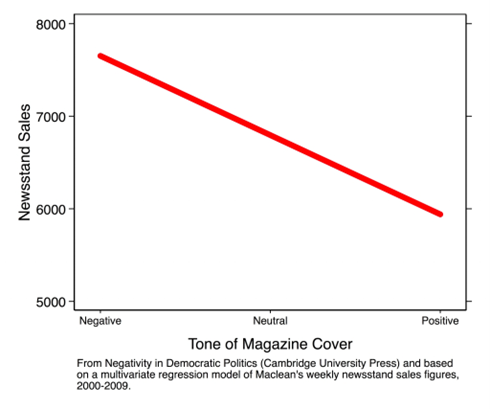

And the fact that we are stimulated more by bad news means that news outlets feed us ever more fear-inducing and dismal content. There’s definite evidence to show this is an effective sales technique.

As the figure from Soroka’s study below shows, news-stand magazine sales increase by roughly 30 per cent when the cover is negative rather than positive.

Our brains hang onto the bad

But, not only are we drawn to the negative stories — we remember them more too.

Some evidence for this comes from a 1998 study by Catrin Finkenauer and Bernard Rime at the University of Louvain, Belgium. Their exploration was simple: they asked participants to recall an emotional event from their recent past.

People were able to remember both positive and negative situations, but there was a significant imbalance in the type of event reported. In two separate studies, individuals reported four times as many negative events than positive ones.

So, sadly, the bad stuff sticks with us.

Driven by negativity

So we are drawn to and remember negativity. But it seems that our judgment is also influenced more by the bad than the good. A 1966 study by Shel Feldman at the University of Pennsylvania explored responses to negative information versus positive information.

Feldman gave participants a description of an individual. Within this description, the person was given either a positive trait, negative trait, or both. Participants were then asked to rate the attractiveness of this fictitious subject.

He found that participants who read the mixed review — with a balance of positive and negative characteristics — rated the subject repeatedly more negatively than you’d expect from the information given. The negative traits were given more weight.

All of this goes to show that, while the world is of course not a place of eternal sunbeams and smiles, if we base our world view entirely on the news, we will certainly see things in a more gloomy light than reality.

Given our in-built attraction to bad news, we have to make an active effort to gain a picture of reality. This is why mental health experts recommend a gratitude practice, which forces us to consider good things.

So I would like to suggest that we humans are resourceful and ingenious. Yes, we may have created some issues — but we don’t know yet how we may resolve them. And while we work it out, let’s not forget how far we have come.

Featured image: Kh-ali-li / Pexels