I am Generation X, often referred to as the sandwich or silent generation. Who cares? I certainly don’t. I really don’t know what this means other than I was born between 1965 and 1980.

To illustrate the irrelevance of generational labels to consumer behaviour, during my lectures for our Brand Management class I asked the students to play a game called ‘Jenni or Maddy’. Jenni being me, Generation X and Maddy being my niece, from Generation Z. There were three questions:

- Who prefers (a) ebooks and who prefers to (b) read physical books?

- Who watches (a) Gossip Girl and who watches (b) Pawn Star?

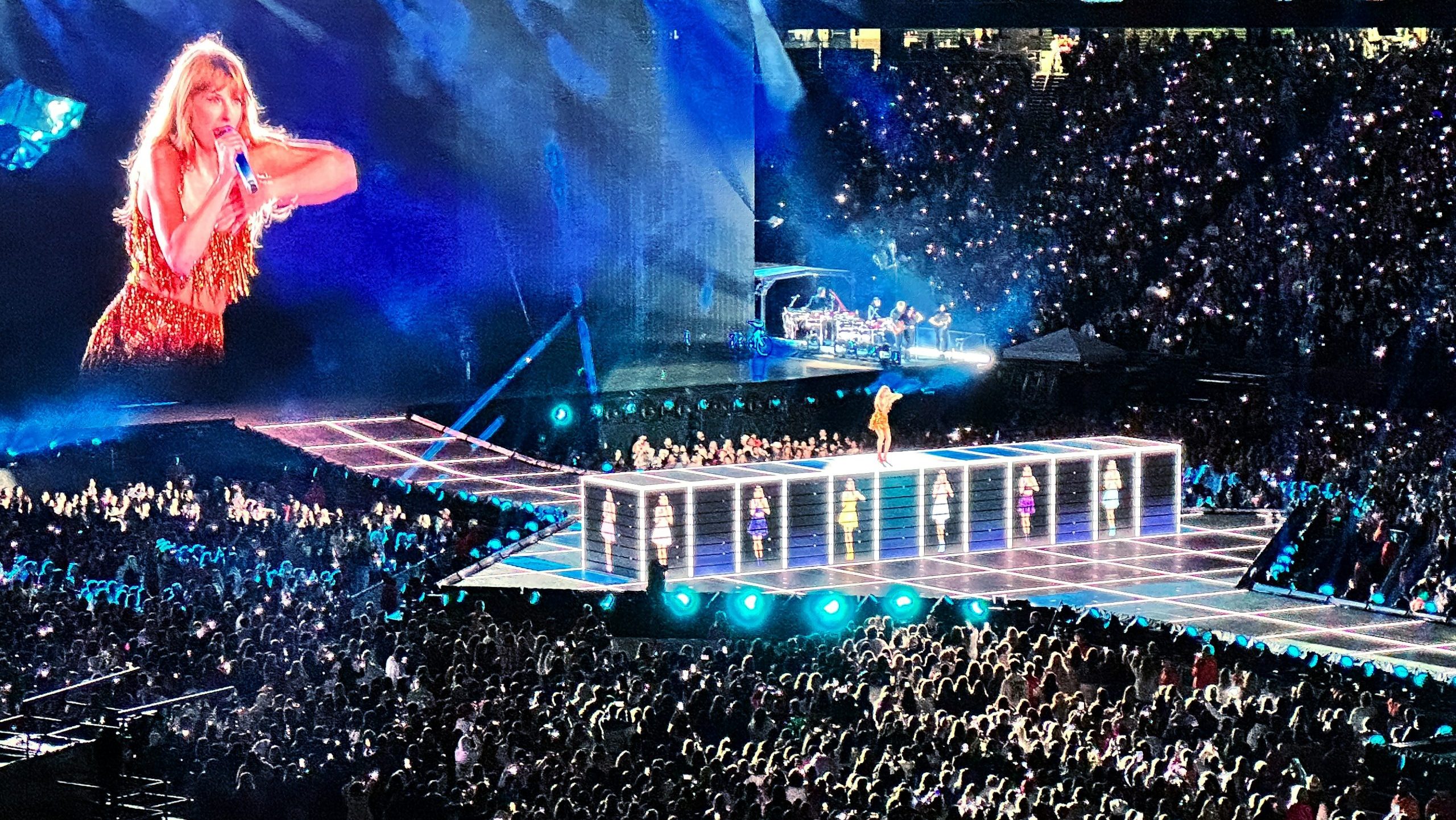

- Who enjoys listening to (a) Taylor Swift and who (b) wants to see Fleetwood Mac in concert?

For all three they would put their hands up for Jenni and (b), but this was incorrect. I prefer ebooks because I travel and read quickly, so don’t want the weight of multiple books. I found Gossip Girl first, and wanted to dress like Blair Waldorf and I just discovered Taylor Swift’s album and was playing that non-stop. In contrast, Maddy liked physical books, tried to get me to go to the pawnshop in Detroit the series is based on and had found herself listening to Fleetwood Mac enough because of her parents to really enjoy their music, and learn all the words to Rhiannon. Yes, it is a simple example, but it just shows how wrong you can be about individual preferences if you make assumptions about age rather than understanding what influences them.

Like astrology, generational classification is meaningless in relation to being able to predict what people will do. Further, as time goes on, these cohort classifications become less and less relevant. It used to be life paths were pretty predictable and so these cohort conclusions were accidentally somewhat accurate. The people you went to school with tended to be who you lived near, and you all generally went through life’s milestones around the same time. One marriage sets off a domino effect for other marriages, one child triggers the same reaction, until one by one retirement happens. Therefore, predicting what people would do based on their age was accidentally correct, because the same people were going through the same life experiences.

We see this in some historical age-related findings. For example, my colleague Professor Robert East found that younger people give and receive more word-of-mouth, while older people give and receive less word-of-mouth. However, this is not a function of age, but rather of (real) social network size. Historically younger people typically know and interact with more people, and have more time to socialise and therefore more people to share with and hear from. While older people, over 55 years, were highly likely to be retired, and your social circle usually shrinks when you don’t have a workplace to go to.

But now we have friends of different ages and a wider range of life paths, from staying single throughout all life, to marriage followed by divorce and moving back home with your parents. Kids can come early in your 20s or later in your 40s. They might be your own children or your new partner’s children from a previous relationship. You might retire at 50 or not retire at all; you might work from home and so not experience the accidental friendships that grow from common interaction in the break room. Age is no longer the indicator of specific experiences, and it is the experiences that matter.

Knowing someone’s birth year tells you just when they were born. Knowing someone’s Western astrological sign tells you approximately what month they were born in. Knowing someone’s Chinese astrological sign tells you what year they are born (as long as you can judge which 12-year band they were born in). And knowing someone’s generation label is just a more inaccurate way to gauge when they were born.

Age is just a symptom of being born on a certain date, not a cause of behaviour. So check your age-based assumptions for deeper explanations to better understand why buyers do what they do.

All the best from me, Jenni

Virgo, Rooster, Generation X

Featured image: MART PRODUCTION / Pexels

Key reference:

East, Robert, Mark Uncles, and Wendy Lomax (2013), “Hear nothing, do nothing: The role of word of mouth in the decision-making of older consumers,” Journal of Marketing Management, 30 (7/8), 786-801.