On the face of it, political and non-political advertising share many similarities, but they also differ in some quite fundamental ways. To illustrate that point, let’s take an example that’s still fresh in the mind: the rise of Nigel Farage and the effect he had on the Brexit vote.

After beginning his career as a euro-sceptic Conservative politician, Farage first became an MEP, then the leader of UKIP, driving a movement to get Britain to leave the European Union. In 2016 he got some version of his wish as Britain voted for Brexit then spent the next four years waiting for it to be formalised. In 2019, Campaign, Britain’s best-known advertising magazine, featured a cigar-smoking Farage on its cover alongside the words:

“‘Advertising? I might fancy it myself one day.’ Love him or loathe him (and it’s a measure of the Brexit Party leader’s success that few are indifferent to him), Nigel Farage knows how to get a simple message across with maximum effect.”

The profile ended with a list of lessons we could learn from Farage:

- Remember that emotions speak louder than reason

- Find a simple message — as succinct as possible — and repeat it consistently

- You can’t please everyone all the time. Find the people who are the most important to you and delight them

- Find a way of making your brand distinctive, with assets you can own, and sweat the details

- Don’t kid yourself that you are the target audience

- Be bold. Not offending anyone is not the cardinal virtue of advertising

- Be yourself. Consumers know if they’re being patronised — by politicians or brands

So far, so difficult to argue with. That list could be well be applied to any successful ad campaign, and it’s difficult to deny that Farage has now spent decades as a famous brand, or that his drive to take the UK out of the EU was an unlikely success, but are the lessons for the ad industry as relevant as they seem? Let’s look at the ways in which the Farage (and Trump) playbook differs, starting with the liberal use of lies to enhance the overall message and its persuasive power.

Farage claimed 70% of UK laws are created by the EU (the real number is 13.2%); he said EU membership costs £55m a day (it actually costs half that, and does not account for the benefits we receive in return); he also claimed that (the untrue) £350m a week would be used to fund the NHS (nope).

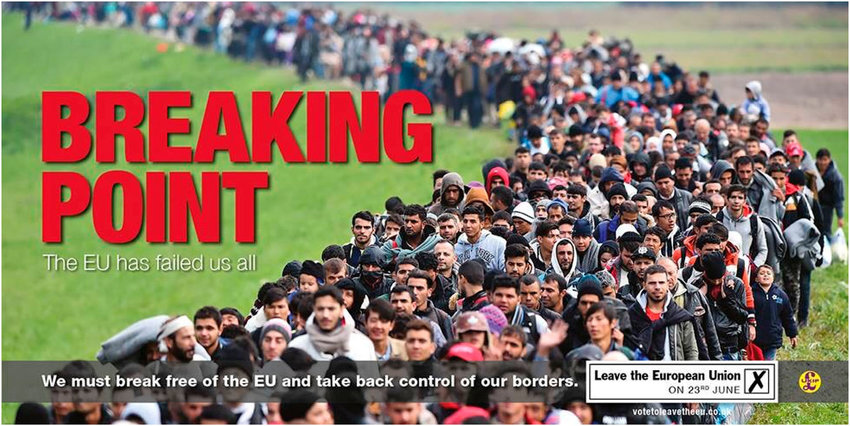

Try doing that with your ad campaign and you’ll be stopped before you start. Advertising isn’t allowed to simply pump out a succession of mendacities to improve one’s own messaging and disparage the competition. Farage also took inspiration from fascism to create a poster headlined ‘Breaking Point’, depicting a long line of Syrian refugees.

It was immediately denounced for stirring up hate crimes, and was condemned by people from all sides of the political spectrum; from Boris Johnson and George Osborne on the right to Caroline Lucas and Yvette Cooper on the left. Some think it ‘worked’ to push the Brexit vote even harder, but does that mean it should be a lesson for advertising to learn from? It fits several of Campaign’s lessons (be bold, emotional and simple, delight those most important to you, and don’t worry about offending people), but Sainsbury’s or Toyota, for example, would suffer an enormous backlash for using the unfortunate victims of a humanitarian crisis to make their communications more powerful.

So the principles are fine, but the lack of additional context — explaining that Farage was able to apply those principles to a subject that was already emotive, add plenty of incendiary lies, and take inspiration from fascism to manipulate people emotionally — is critical.

He was allowed to play by another set of rules, and those deviations were a critical reason for his success. There are probably some great boxing principles that tell you how to attack and defend effectively, but if one side is allowed to use a knuckle duster and a flamethrower, those principles remain true but become pointless.

I’m sure there are plenty of supporters of Farage who would call him a ‘winner’ who is happy to break the rules to achieve his goals. And that’s fine, but then there needs to be an explanation that rule-breaking can be another useful principle, but one that advertising would find much harder to apply.

It’s certainly true that political and non-political messaging are very similar, but the ways in which they differ make all the difference. Taking lessons from Nigel Farage might seem like a good idea on the surface, but dig a little deeper and you’ll find that his real path to success isn’t necessarily open to the rest of us.

Featured image: Matt Brown / Unsplash