If I were asked, if we live in an age of discontent and had less than 10 seconds to decide on the answer, I’d most likely yell: Yes! To explore one of the factors possibly creating discontent in current times, I will however base my exploration on something more substantial than my gut feeling. Despite being ancient, it still fascinates and teaches some of the most brilliant academics of our time: Buddhist thinking.

In Buddhist tradition the root of all suffering (or discontent) is split into two types. The first is the inherent suffering, which originates in physical pain, death or the loss of a loved one. The second type is caused by a thirst, a clinging or a craving for things that the Buddhists would consider not essential for life. Inherent suffering is part of the human experience and shared across generations. But also greed, attachment and craving are no inventions of the 21st century.

So what would make me jump to my feet and scream ‘yes!‘, at the question of whether we live in an age of discontent? If inherent suffering has remained at a similar level and we assume that we do live in age of discontent, we need to explore the second type of suffering in more detail.

To do so we will explore two questions: Why are we craving more? And: Why are we craving things we don’t need for a good life?

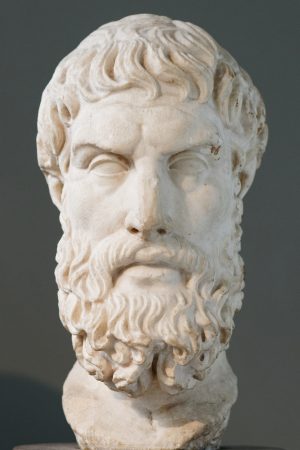

Epicure and the happy dog

While writing a copy for an online pet shop, I realised something interesting. I had to describe what different breeds needed in order to have healthy, long — and good — lives. It was an easy (and slightly repetitive) formula: they need mental and physical stimulation, good nutrition, time out in nature and company (whether a family or a caring dog owner). By describing it over and over again I thought to myself: isn’t this exactly what makes a good life for humans, too?

In fact, humans are social animals and meaningful relationships have proven to increase longevity and overall resilience. The same goes for the effects of nature and being outdoors, eating a balanced diet, as well as having stimulating and fulfilling work. The positive impact of these factors is backed by modern science but is also not new to human thinking. Even in ancient Greece, Epicure’s philosophy on how to life a good life was describing a similar formula.

Maybe we know about Epicure’s philosophy, maybe some of us own a dog and try to ensure they have a good life — but: how many of us city-locked, hip, urban singles with freelance jobs live according to this formula, while hunching over our laptops for most of the day?

In a way, discontent can feel like a privilege. How else can some people seem to have it all and be discontent, while others seem satisfied with very little? To have the time to be dissatisfied with life almost assumes that important needs, such as food and shelter, are covered. Yet, we established the common young urban professional lacks what Epicure — and pet shop owners — preach for a long and happy life.

Instead of fulfilling the basic needs for a good life, we are infiltrated with new needs every day. Needs created to sell products. If we were focusing on living a good life, we would be bad costumers.

Living a good life also seems like hard work compared to the glossy, carefully packaged, silk-wrapped promises made to us by angelic, pore-less creatures on our screens. Why deal with the pain of real connection that one encounters in relationships, when a lip gloss promises us that self-love is what’s its all about? Why walk through a forest when there is a spa around the corner, where they do everything for you, ‘just swipe your card here‘? Yet those aren’t the only needs we are being sold to stay thirsty.

Comparison and the pain of being ordinary

The weight of assumed possibilities today forces many of us to feel inadequate. In a world that showcases tech millionaires, influencers and entrepreneurs, as all self-made and results of a superior work ethic, the pressure to be extraordinary — a success — can be all to prominent. Similar to the emergence of the internet as a pool for equal opportunities, social media seduced us to think that everyone could become famous — but only a handful did. Despite there being a few lucky (and maybe also hard-working) individuals, who have climbed up the Mount Olympus of online fame, it is — like it always has been — a shorter distance for some. Mainly for those coming from money and influence.

It is easy to imagine a maid of the 19th century to be dissatisfied with cleaning her employer’s beautiful dresses, while being fully aware that she will never wear anything as beautiful or dance at one of the candlelit banquets. However, she would have had one advantage to the person of today. Unlike the young woman following Kim Kardashian on Instagram, the maid then knew that it wasn’t her personal fault for not being in her mistresses position. She wasn’t told that, if she tried just a little harder she could be anything and while this by no means is painting a pretty picture but rather a bleak one, the maid ultimately had no illusions about her possibilities.

In a society that pretends that everyone has equal chances, it is on us to start a company, publish a book, write — yet another — inspiring podcast. We maintain the illusion that if we only buy the right products and work hard enough, all what is reserved for the divine can be ours. If success eventually feels out of reach, marketing is again ready to help. You failed to be a famous model like Bella Hadid? You can spend money on surgical and non-surgical procedures to look like her. You failed be a talented footballer like Ronaldo? You can buy the sneakers he — allegedly — wears.

Further reading: Dr. Siegel’s ‘The extraordinary gift of being ordinary: finding happiness right where you are‘

Featured image: Johann / Pexels