Chaka Khan sang it best: ‘I’m every woman, it’s all in me.’ Nowadays, there’s a closet full of women to shrug on — or rather, girls. Girls are everywhere. The Cool Girl is forever immortalised in Amy Dunne’s infamous Gone Girl monologue, ‘hot and understanding’ and dissected in many a think piece. The Girl Boss first stomped onto the scene in 2014, taking down the patriarchy in her punchy-coloured pantsuit. Today, TikTok tells us that you can be a ‘Clean Girl’ or a ‘Dirty Girl’, a Vanilla Girl (or if you’re a woman of colour, another coffee-inspired flavour). If you wish really, really hard, you can even be a Lucky Girl. You can be any kind of girl you can conceive; that’s the legacy of Girl Power.

I’m a ‘Zillennial’, the microgeneration between Millennials and Gen Z (sounds like an arbitrary distinction but we make up 40% of consumers). For me, Girl Power is synonymous with the Spice Girls, but the slogan’s roots are more radical. Punk band Bikini Kill coined ‘Girl Power’ in the title of their 1991 zine. This zine contained ‘The Riot Grrrl Manifesto’ — a passionate, political and anti-capitalist statement and keystone in the punk subculture. The manifesto embodied the ideas of an entire movement of outspoken, unfiltered women, who rallied to ‘normalise women’s anger, celebrate sexuality’ and redefine the status quo.

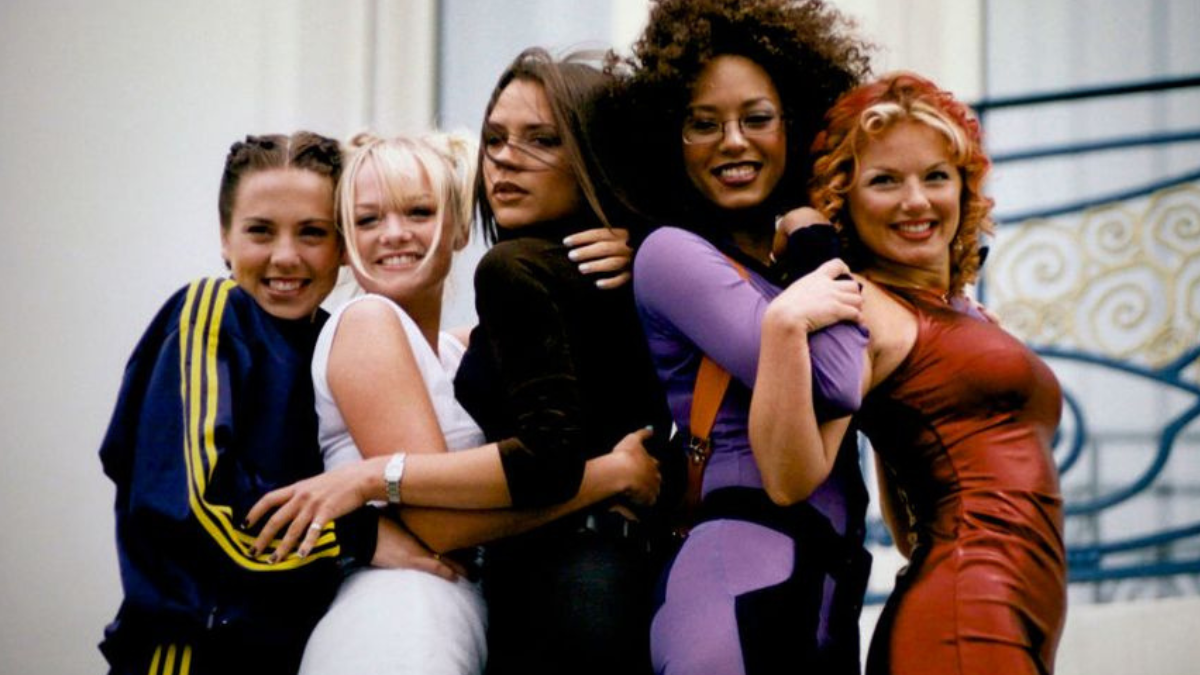

Yet it’s the Spice Girls that mainstreamed Girl Power…

From the ubiquitous ‘If you wanna be my lover, you’ve gotta get with my friends’ to ‘God help the mister that comes between me and my sisters,’ the band’s lyrics preach solidarity in sisterhood. For me and thousands of girls across the globe, this was our first taste of feminism. Sure, it was simplified, sanitised empowerment that’s shallow by 2023 standards — but wasn’t that kind of the point? The Spice Girls were speaking directly to little girls. They were the first to show an entire generation that they can be louche and lairy; to believe in themselves and stand up for their friends. The Spice Girls made feminism accessible and fun — and significantly, marketable.

‘The Spice Girls were a death knell for feminism,’ declares Tanya Gold in The Telegraph, and in some ways, that’s true. It’s the Spice Girls’ colossal success that commodified Girl Power. The market took an iconoclastic political movement and Barbie-fied it — pulled out its teeth and slapped it onto pencil cases, t-shirts, and posters to hang on children’s walls. Now Girl Power was the mantra of the capitalist masses, yelled out by Sporty or Ginger or Baby at their concerts for tween fans to echo back. It was a watershed moment, but not for the subculture. As Cristina Arreola writes for Bustle, ‘major marketers recognized the muscle of girl power and flocked to hook teen girls early.’ As fast as you can say zigazig-ha, brands began cashing in. Pepsi, Polaroid and Walkers Crisps are among the many that enlisted the Spice Girls to help flog merchandise. A slew of campaigns followed, from Nike’s If you let me play to Revlon’s What makes a woman unforgettable, all aimed to appeal to women and young girls. ‘Girl Power had morphed from rebellion into a miasma of consumer ideals,’ and with it, femvertising emerged.

And what became of us women fattened up on Girl Power?

We were empowered, but entitled; told that we could have it all and fed to a world where we couldn’t. ‘If this is a man’s world, who cares?’ decried Sophia Amoruso, the #GirlBoss SHE-O herself. ‘I’m still really glad to be a girl in it.’ Amoruso’s memoir captured the zeitgeist of 2014 and for many young women, offered a new way to rebel against the big Patriarchal Power Problem. Girl Boss was 90s Girl Power all grown up. Girl Boss was cool, collected and respected — she got her career and her fairytale ending. She raised women up, created space at the table; she created change. At least, that’s what all those inspirational Instagram posts wanted us to believe. The reality is that pinkwashing feminism and dousing it in glitter prevents progress. There’s a reason there aren’t any #BoyBosses — they’re just bosses. This distinction further othered women, and created a clique where only the pink, placid and palatable can thrive. Girl Boss certainly wasn’t fighting for everyone. Her ‘Future is Female’ t-shirt rings hollow when she doesn’t give a fuck about the underpaid woman who sewed each sequin on. Fortunately, it didn’t take long for us to see through her glossy, shallow veneer.

When Simone de Beauvoir said, ‘one is not born, but rather becomes, woman’, she wasn’t streaming Netflix. At some point, those ass-kicking heroines we’d tune into on Sunday mornings were replaced by other girls — New Girls, 2 Broke Girls, Girls. ‘I may be the voice of my generation,’ Hannah Horvath declares in Girls‘ series premiere, and myriad writers clamoured to agree. All of these shows have one thing in common; they centred on the lives of mostly white, financially-struggling twenty-to-thirty-something women, navigating the foibles of millennial adulthood. In my early twenties, I connected with these characters; they were imperfect and unapologetic, flighty and flawed. It felt a bit like picking your favourite Spice Girl again: were you a Marnie or a Shosh, a Jess or a Cece? These girls were messy and real, but they were perennially girls. And as Julie Klausner chides in Don’t Fear the Dowager, ‘it’s much harder to bring down a woman, or to call her a moron, when she’s not in pigtails and Ring Pops.’

Personally, I think women can wear their hair however they want, but I see her point. Being called a ‘girl’ can feel infantilizing. One study showed that women who were referred to as ‘girls’ felt less confident, believed that others would view them as less prepared for leadership roles and perceived they had fewer leadership qualities. ‘Prefacing engineer, architects, doctor with “female” or “lady” makes it clear that they are seen to be a woman first, and professional second,’ Professor Kate Sang told Glamour. Of course women want and should be treated equitably — but isn’t rejecting our girlhood playing into patriarchy? From Taylor Swift to Twilight, the things that were popular among teen girls in the 2000s were mocked so extensively that many of us grew up insisting that we’re ‘not like other girls’. Girlhood is only puerile and weak if we keep believing it is.

Lately, there’s been a reclamation of the word ‘girl’ in pop culture

The Girl Museum is a virtual platform that celebrates the achievements and experiences of girls, challenging the idea that young women are passive and powerless. Pop giants like Beyonce, Lady Gaga and Lizzo all use the word ‘girl’ in their lyrics and branding as a way to celebrate female empowerment and challenge traditional gender roles. The legacy of Girl Power lives on in places like TikTok, where #girlpower has over 15 billion views.

My favourite trend last month was ‘She Lives Inside of Me’, where women worldwide shared childhood videos, celebrating the free-spirited little girls they once were. And they deserve to be celebrated. It’s those girls that we were yesterday — the ones who believed that they could be anything — who grew up into the feminists of today.

Featured image: Spice Girls / Flickr