I occasionally jest with non-advertising friends who complain about ‘surveillance’ marketing and suchlike; that if they want to avoid being targeted online, forget about adblockers, anti-tracking or VPNs. The one weird trick for invisibility is to set the birth year on your profiles to somewhere between 1965 and 1975, and no advertiser will pay any attention to you. Despite a portion of so-called Gen X consumers contributing more than half of consumer spending in developed markets, only 5–10% of marketing budgets are directed at reaching them. They are pretty much ignored. Probably because they don’t feature in 90% of consultant decks.

A wee bit of history…

The first generational label that gained any traction was the ‘baby boomers.’ This term came into use in the late 1940s and 1950s following the unprecedented birth rate spike after World War II. The sociopolitical and economic implications of this massive cohort caught the interest of demographers and sociologists. This period marked the initial recognition that a collective group shaped by a similar set of experiences could have unique cultural and consumer behaviour traits. But it was more a cultural ‘event’ than a segmentation tool.

By the the time the swinging 1960s came around marketers started to recognise the potential of appealing to this large, influential group of teenagers, who were now coming of age and wielding a new spending power and independence that previous generations of kids had not.

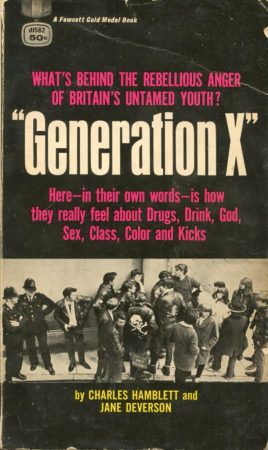

In their influential 1964 book Generation X Jane Deverson and Charles Hamblett went on a sociological exploration of these British teenagers. One of the earliest cultural anthropology things, Generation X, steps into the world of mod youth, capturing their attitudes and lifestyles through interviews and firsthand accounts, describing a generation searching for identity and autonomy — a powerful, early document of youth rebellion. Ironically, the teens Deverson and Hamblett described as Generation X are today what market researchers call boomers. Confused? You will be.

So, although this generational labelling seems to have been around forever, the formalisation only really became pronounced with the works of sociologists and authors like William Strauss and Neil Howe. In their influential 1991 book, Generations, they detailed their theory of recurring generational cycles and defined cohorts, such as the Silent Generation and then Generation X (as the post-boomer cohort).

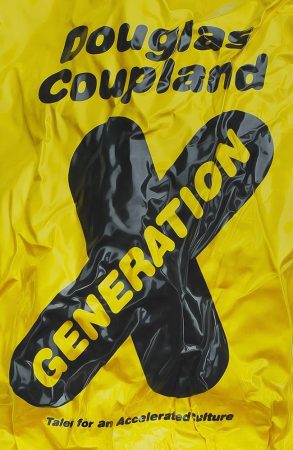

Gen X was further popularised in the 1990s, largely due to Douglas Coupland’s slacker novel Generation X: Tales for an Accelerated Culture. These couple of works effectively set the stage for the boom of generational analysis in media, business, and academia and the classic misinterpretation of the work by market researchers that we are stuck with today. The appeal was clear. Segmenting large groups by age promised a way to predict behaviours, attitudes, and preferences with a broad brush. The trend expanded with the rise of millennials in the late 1990s and early 2000s. This cohort was the first to grow up with the internet, which seemed to create a cultural and behavioural distinction that marketers and researchers were eager to dissect.

The media’s fascination, firstly with millennials and then Gen Z, propelled generational analysis into the mainstream zeitgeist, turning it from a niche academic interest into a global conversation.

While generational segmentation remains ridiculously popular, its utility is increasingly being questioned by psychologists, smarter marketers and human nature enthusiasts like this author, who argue that it oversimplifies consumer behaviour, and there are perfectly good empirically grounded cultural models already available to researchers. Life stage, social class, and shared universal human motives reveal far more about consumer patterns than generational labels do. Still, the generational framework has persisted.

Why might these generational labels have become currency?

Aside from the obviously tidy, headline-ready convenience of tags like Gen Z, human beings — and I include marketers in this category — are wired to simplify. Our minds crave categories; we sort, label, and package complexity into digestible pieces to make sense of a world too vast and varied to contemplate all at once. Generational labels, with their broad strokes and archetypal shorthand, are an irresistible solution to this ancient mental itch. They promise understanding with minimal effort, a way to group millions into a singular, relatable story.

But this attraction is not just about efficiency — it taps into a more profound human need for narrative. Labels like boomers and millennials offer the allure of a coherent narrative, a way for marketers to weave the chaos of consumer behaviour into a simple story that makes sense, even if the threads fray at closer inspection.

(It is typical of a bigger malaise that can be called functional stupidity — a specific kind of deliberately constrained thinking. It’s not about an absolute lack of intelligence or incompetence; rather, it’s about a deliberate or subconscious avoidance of deeper critical thinking, and reflection. It’s functional because it helps organisations maintain coherence, efficiency, and harmony, but it is also stupid because it suppresses challenging ideas and limits adaptive thinking. This lack of any real analysis creates an environment where decisions are made based on accepted norms or superficial reasoning rather than rigorous scrutiny or innovative thought. But that’s another article.)

The fact (if that matters) is that generational markers are a distraction from understanding what truly drives behaviour. Human beings aren’t products of neat, twenty-year slices of culture. We’re creatures shaped by an ancient and enduring biological rhythm.

Here are approximations of a couple of the generational myths: millennials are nostalgic optimists, wrapped in eco-conscious anxiety and laden with student debt. Gen Z, meanwhile, is anxiety-ridden, attention-deficit multitaskers with a penchant for authenticity, or at least the Instagram-filtered version of it. By this same logic, the Gen X billionaire tech mogul and the suburban parent with a part-time job supposedly belong to the same generational story. The millennial in their mid-thirties navigating parenthood has little in common with their twenty-something counterpart, freshly navigating the job market.

My Generation by The Who isn’t just a song; it’s the primal scream of pilled-up youth, an amphetamine manifesto drenched in feedback and the jagged shards of mid-60s disillusionment. It’s the sound of a generation straining at the seams of their constraints, a riotous declaration that is equal parts sneer and anthem. It’s an audio flashpoint where bravado meets fragility — Daltrey’s stuttered, defiant ‘f-fade away’ is not just an affectation, but a crack in the façade, a moment of pure, involuntary honesty in an era strung out on cheap speed and existential angst.

It’s not just My Generation — it’s our rejection of yours. The youth explosion of 1964, now it’s a boomer anthem!

Taking an evolutionary lens to generations points us toward a more meaningful framework. This is where we find the common ground that matters. The restless energy of youth seeking status and novelty, the weight of middle age focused on legacy and stability, the reflection of later years searching for fulfilment — all of these are archetypal experiences transcending generational silos. The 25-year-old Gen Z graduate eyeing their first big break shares more in common with the 25-year-old millennial of a decade ago and with their own boomer grandparents at the same age, despite cultural changes. The life stage defines their needs far more precisely than a generational label ever could.

And then there’s social class, the great unspoken reality that slices through generational lines more sharply than any label. Class shapes everything from consumer behaviour to market design, influencing what people buy, how they perceive value, and what aspirations they can realistically hold. The working-class Gen Z’er and the working-class boomer have more in common than marketers care to examine. Their relationship with money, their brand affinities, their view of necessity versus luxury — it’s all steeped in the shared experience of class, not in the fact that one grew up with Snapchat and the other with four TV channels.

What about marketers’ current obsession with Gen Z?

On the one hand, the generational label and assigning special quasi-mystical attributes is silly for all the reasons we’ve discussed. However, paying attention to the timeless drivers of behaviour among young adults will always pay. A failure to attract new-to-market buyers is a robust early warning sign of brand decline. It reflects a decrease in buyer numbers and a loss of relevance and presence. I once did a quick turnaround strategy salvage job for a firm that couldn’t work out why their penetration was tanking year on year, to critical levels. We quickly discovered that their customer base was dying of old age.

The search for security, the pursuit of status, the need for belonging—these are the rhythms that play out throughout a life, adjusted and refracted through the lens of age and class but never disappearing. A young media planner chases status not because they’re Gen Z, but because its what young people do. A retiree is looking for stability not because they’re a boomer, but because they’re approaching the last lap.

These needs are recurring generational cycles, universal, ancient and deeply human.

And yet, this GenX’er reckons lazy generational segmentation will likely hang around for a while. Identifying and classifying the next new generation isn’t just a demographic shift. It’s also the consultants’ lifeline, an evergreen justification for the next round of research, analysis, and fees. The real game isn’t about identifying truth; it’s about keeping the generational myth alive so the cycle can begin anew.

Or whatever.

Featured image: Remy Gieling / Unsplash