When asked that age-old question of “which superpower do you wish you could have?”, time travel is a notoriously common answer. It’s called a superpower for a reason, though – we can’t actually do it. However, if we want to get as close to it as humanly possible, our best recourse is nostalgia.

Nostalgia is a powerful way to unearth joyous artefacts of a bygone era. It brings us pleasure to recount unadulterated youth, or remember better times. What’s more, the emotion nostalgia can generate makes it a compelling tool in the world of marketing.

As a potent weapon for brands to build trust, to evoke emotion and to reinvigorate modern campaigns, nostalgia offers a chance for brands to associate themselves with something that their audience already adores.

However, nostalgia does not offer up a guaranteed ticket to success. There is room for failure; for brands to use nostalgia to their own detriment. Resultantly, as well as considering the propensity for nostalgia to catapult brand building, organisations must also contemplate how they can “reimagine” it, so to avoid getting stuck in the past.

How nostalgia can be a powerful tool for marketers

Research suggests that nostalgia can be an antidote to anxiety and loneliness, as well as being a powerful way of coping during difficult life transitions. Now more than ever, in the wake of the pandemic and facing the spiky jaws of a global cost-of-living crisis, the consumer desire for emotional satiation, familiarity and memories of a better time are at their zenith.

In culture, we tend to observe nostalgia in a cyclical nature – core identities of art, music, fashion & even political rhetoric tend to return to the surface after several decades have passed. Take the resurgence of vinyl records, 90s fashion and film cameras, for example; their recurring prevalence proves that the past still shapes our present.

In a marketing context, nostalgia has been a powerful vehicle for multiple campaigns, whether it be through drawing on brand heritage, resurfacing discontinued brand assets, releasing products with a retro aesthetic or using a nostalgic theme in the tonality of advertising.

A recent example came from Great Western Railway reviving Enid Blyton’s 1942 novel series ‘The Famous Five’, in a campaign that seeks to spark people’s love for rail travel. The books were a childhood staple for a large cohort of Brits throughout the 70s, 80s and 90s, and the campaign takes consumers back to those times, striking an emotional and quintessentially British chord.

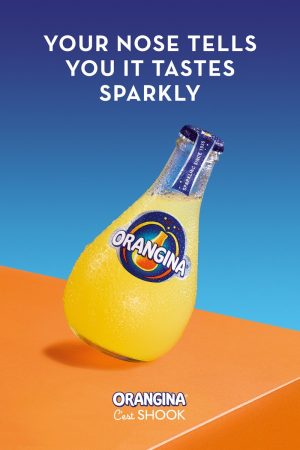

Orangina also delved into nostalgia marketing with their 2015 relaunch. The drinks brand brought back its heritage visual and experiential equities – the bulb-shaped bottle and its ‘shake to wake’ ritual. Mike Teasdale writes in WARC: “I started buying it again because it reminded me of being a kid and drinking it on holidays at the seaside. Job done.”

These campaigns succeeded because they had a heritage to lean on; be it a story etched in our national culture or an ergonomic familiarity. Brands that are in possession of an emotionally rich past would do well to draw upon it, especially during times of crisis to remind consumers of better, more stable times.

The pitfalls and peaks of nostalgia

So how can brands use the past to help future-proof their brand and campaigns? By virtue of being a popular marketing tool, nostalgia risks being a saturated tactic. There is a danger that brands get stuck in the past, failing to offer something new, which can pose damaging threats to their integrity. For example, brands that have innovation and futurism at the core of their values may well find that using typical nostalgia communications creates contradictory messages, fracturing the brand’s legacy.

Take Apple for example. Apple, a 45-year-old tech brand, has a prominent legacy in the tech space. Despite this, the brand’s identity is rooted in freshness and innovation, so if they are to look back in time, it should be done carefully. Consumers buy Apple products because they pioneer new technology; reminiscing about older, slower, clunkier times, without also displaying innovation, could threaten that image.

On the other hand, Pizza Hut’s 2021 Superbowl spot took a trip down memory lane, employing new ambassador Craig Robinson to successfully reignite customers’ memories of childhood trips to the restaurant. From vintage visual cues to Robinson’s ‘kid at heart’ character role, the campaign touches on some of the insights that made the chain a staple in many American children’s upbringings. To steer the work into the 21st century, Pizza Hut created an AR arcade game, giving customers the chance to win prizes, as well as re-releasing iconic pizzas with modern twists.

It’s clear that nostalgia isn’t going to work as a blanket tactic for brands. Some will benefit from an unwavering forward-facing stance, as that is what their loyal customers expect. In other cases, a smart, novel look back over the shoulder has the power to trigger a considerable surplus in brand love.

In a country like the UK, with such a multicultural population, it’s important to be sensitive about how nostalgia-led strategies will land with audiences whose backgrounds are not dominant in the local culture – at best, it could just mean some people sit through a baffling ad, but it could potentially trigger memories of times when discrimination was overt and widespread.

One way to mitigate this is through identifying elements of the brand that bypass cultural nuances, such as old product features. Coca-Cola employed this tactic with their campaign celebrating the 100th anniversary of their famous glass bottle. By opting for a product-driven approach to nostalgia marketing, Coca-Cola cast the net wide, offering an inclusive look back in time.

The antidote to the possible pitfalls of nostalgia marketing

With all of the above in mind, the clear antidote to the lurking pitfalls of nostalgia marketing is for brands to have a granular understanding of their history in relation to their consumers. If they do find themselves in a position to look back in time, offering up something new to customers is crucial. Yes, people are increasingly looking for emotive comms that resonate, but not at the expense of a unified brand offering with rational benefits too.

In a nutshell, brands should consider whether they can not only reimagine old ideas and traditions, but reimagine the way in which they reimagine them.

Featured image: Craig Robinson Dot / Pizza Hot