In an episode of his genre defining podcast, Adam Buxton interviews the Chilean novelist Isabel Allende and asks her about her legacy. Her answer was remarkable enough that it was the first thing I thought of when I saw this month’s topic:

I don’t believe in legacy — that’s a penis word. Men think in terms of legacy and transcendence, women are more realistic. No one is going to remember me except my grandchildren once in a while. Immortality doesn’t exist, you might have a statue somewhere, who cares? You’re dead.’

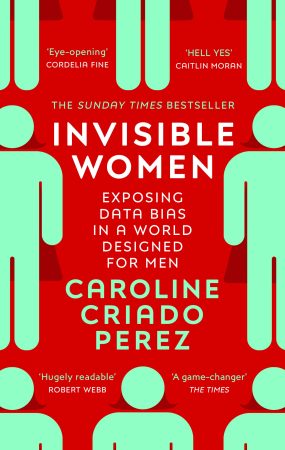

This sense that legacy is a ‘penis word’ is substantiated broadly by the names on buildings all over the world, which, by definition, is telling. Legacy, beyond its primary original meaning of one’s inheritance, means anything that is transmitted from the past that still retains purchase in the present and men dominate such. As Caroline Criado Perez once noted, an observation that germinated her book Invisible Women, all the statues in Parliament Square were of men, until she campaigned to get a suffragist leader recognized.

More broadly, according to Art UK, women only account for 15% of the statues dedicated to named people, which is only 4% of all the public sculptures in London. The evidence certainly suggests legacy is a male concern, but it’s hard to disentangle that from the overall effects of a patriarchy in the UK that didn’t allow women to open their own bank accounts until 1975, about one hundred and fifty years after slavery was abolished.

There are obvious evolutionary-psychological interpretations of why men should be more obsessed with their legacy. I’ve always believed that the Romantic poets focus on originality — a novel concept in literature at the time — was precipitated by creative insecurity caused by the displacement of the divine as prime mover, and the obviousness of women being the font of creativity, since they literally make life. To avoid allowing women to assume the apex position in creativity, men decided their brain children were more important than their female produced progeny. That legacy continues.

Not that long ago, apart from amongst the anachronism of our remaining royalty, and almost certainly in part due to the Nazi obsession with it, bloodline ceased to be the primary vehicle of legacy. The pan-European royal instinct to diminish their gene pool through generation of inbreeding led to many unfortunate inherited conditions, most famously haemophilia, which became known as the ‘royal disease’, which wasn’t the kind of legacy they were hoping for.

Today, the rulers of our world are rarely royal, coronations notwithstanding

It is the titans of industry who are most concerned with their legacy, seeing themselves as the rightful inheritors of such status because of the money they captured at points of inflection. If one was to make broad generalizations, it would seem that the most famous of the robber barons of a century ago — Vanderbilt, Carnegie, Rockefeller — were alive at a moment of inflection in the techno-economic infrastructure of their world and managed to capture the lion’s share of it. The same could be said of Moore, Jobs, Gates, Musk, and, until recently, Sam Bankman Fried. After a century or more, the only remnants of the robber barons’ reputations that remain are names on institutions, libraries and such all over the world. As Anand Giridharadas has written about at length, what we currently think of as philanthropy is better understood as reputation washing, where the wealthiest are unwilling to pay taxes to the same degree as the rest of us, but instead use tiny amounts of their gains to lobby and bestow largesse however they see fit, circumventing the democratic distribution system of taxation in favour of their own interests, and putting their names on everything. Most of these billionaires in the USA claim to be Christian, but their eponymic needs don’t chime well with Matthew 6:4 ‘That thine alms may be in secret: and thy Father which seeth in secret himself shall reward the openly.’ Hypocrisy never seems to concern the rulers of the world in any age.

What about the rest of us?

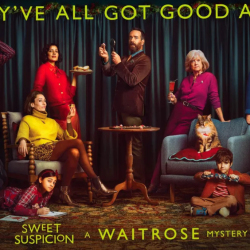

You and I are not titans, barons or moguls, what should we care about legacy? Advertising is ephemeral. Despite how clearly you can remember jingles from your childhood, no one remembers nearly all ads. Even adgeeks like myself can only pull a few exceptional examples from the much lauded creative revolution, for example, most obviously the DDB VW campaign (but try to name another… I’ll wait).

What legacy can an advertising person hope to have? In the Disney movie Coco, they refer to the concept of second death, explaining that ‘when there is no one left in the living world who remembers you, you disappear.‘ This line is a legacy in the sense that it has been written before. The line ‘it is only when no one remembers that you are truly lost. That is the true death‘ appears in a book called The Sorceress by Michael Scott in 2009, and if I cared to research further I’m sure I could find earlier antecedents. The point being that nothing comes from nothing, we are all using language and concepts coined by our forebears, adapting them to our current needs.

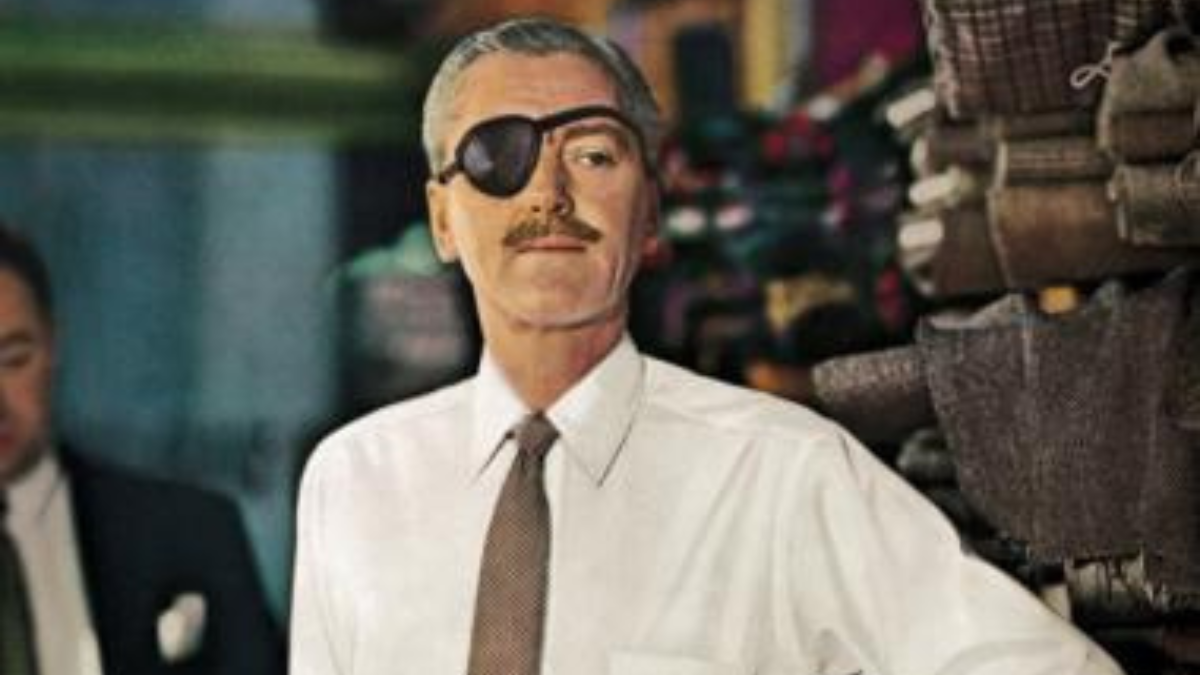

Outside of the industry, I assume very few people currently think about Lemon or The Man in the Hathaway Shirt (no jingles on print so…).

Arguably, even beyond the global agencies that currently bear their names, the main reason Bernbach and Ogilvy are remembered to this day in our industry is their writing. Their pithy encapsulation of the challenges and spurs of advertising are endlessly reinterpreted for current needs. However, one might also consider what the legacy is for advertising as an industry, uniquely positioned in between culture and commerce, the lubricant of consumerism and business model for the media. It’s far from simple, and binary arguments are naive, but for those of us considering our next phase of life, it’s worth mulling over the legacy advertising left us with, and what we left as legacy for the world. One obvious consideration takes us back to penis words, considering that the industry is still dominantly white men and lacks equitable representation throughout, including in our work. Despite two decades of Dove, two-thirds of women in the UK believe that advertising is at least partly to blame for the recent rise in eating disorders among young women (which 37% between 2016 and 2019); and 75% say ‘the way models look in advertising makes women feel bad about themselves and are harmful.’

Equally, part of the stain of historical patriarchy is the elision of women’s contribution to the evolution of advertising thus far. Various forms of gatekeeping ensured the canonical texts referred to above are written by men. That’s why, as I was reaching for a conclusion to this screed, I was delighted to see that Channel 4 has recently screened Mad Women — honouring some of the women behind classic ads.

It is debuting in honour of the 100th anniversary of the founding of WACL – Women in Advertising and Communications leadership — which has worked tirelessly to address our imbalance. The show is being funded by Diageo, Google, Tesco and Whalar (does that make it branded content or nah). The work continues because ‘the battle for women to be equal contributors to all parts of the ad industry — and particularly the creative department — has been long and arduous. We’re not there yet but, in our 100th year, it’s good to celebrate how far we’ve come, whilst looking forward to how we can continue to inspire, support and campaign for the women in the industry to accelerate this much needed change.‘

Is a television documentary enough to change a century of legacy? Probably not but The Social Dilemma seemed to elevate the discourse about the negative externalities of social media into the mainstream and, well, every little helps.

Featured image: The Man in the Hathaway Shirt