Our lives are inextricable from open source. It’s the foundation on which the internet was built, and what continues to power digital progress today. Recent reports suggest that 96% of contemporary software contains open source code. The movement evokes a sense of idealism, transparency and community-driven innovation.

But what happens when open source meets AI?

Last month, nonprofit LAION announced ‘Open Empathic’ — a project that plans to bring emotion-detecting AI to every developer, everywhere, at no cost. You’ve no doubt encountered their influence. Much of the recent proliferation of generative AI derives from LAION’s sprawling index of open datasets and machine learning models. Their database supports popular generator Stable Diffusion, an open source contender to proprietary models DALL-E and Midjourney.

Now, Open Empathic aims to ‘equip open-source AI systems with empathy and emotional intelligence.’ What does this mean in practical terms? Great things, insists Founder Christoph Schuhmann. In the near-future, this technology could transform our daily lives. It could provide virtual therapy to vulnerable people, bring customised learning into classrooms and adapt gameplay instantaneously. In time, it could revolutionise the marketing industry; picture customer service chatbots that care (or at least, do a great job pretending to), self-adjusting social media posts or ads that independently suggest products based on the viewer’s current mood.

It’s easy to be dazzled by the endless opportunities

It was only last November that ChatGPT launched and marked a seminal moment in our relationship with AI. It cleaved public opinion; many shared fears ranging from technological unemployment to outright human extinction — and yet, a year on, it seems plenty of us have succumbed to its allure.

But what do we sacrifice in pursuit of this enterprising convenience? What could universal, emotion-detecting AI actually mean for society at large?

Imagine a world under perpetual emotional surveillance. Here, our facial expressions are evaluated, movements monitored, the inflection of our voices decoded, at all times. Sensors that read and respond to our every gesture exist in our most private objects. This omnipresence of emotion-detecting AI, whilst promising smooth, personalised and unparalleled experiences, could lead to a society moulded by conformity; a world where fear of judgement shapes every smile, step and spoken word.

As AI continues to integrate more deeply into our daily lives, are we headed towards an unprecedented panopticon?

The panoptic paradox

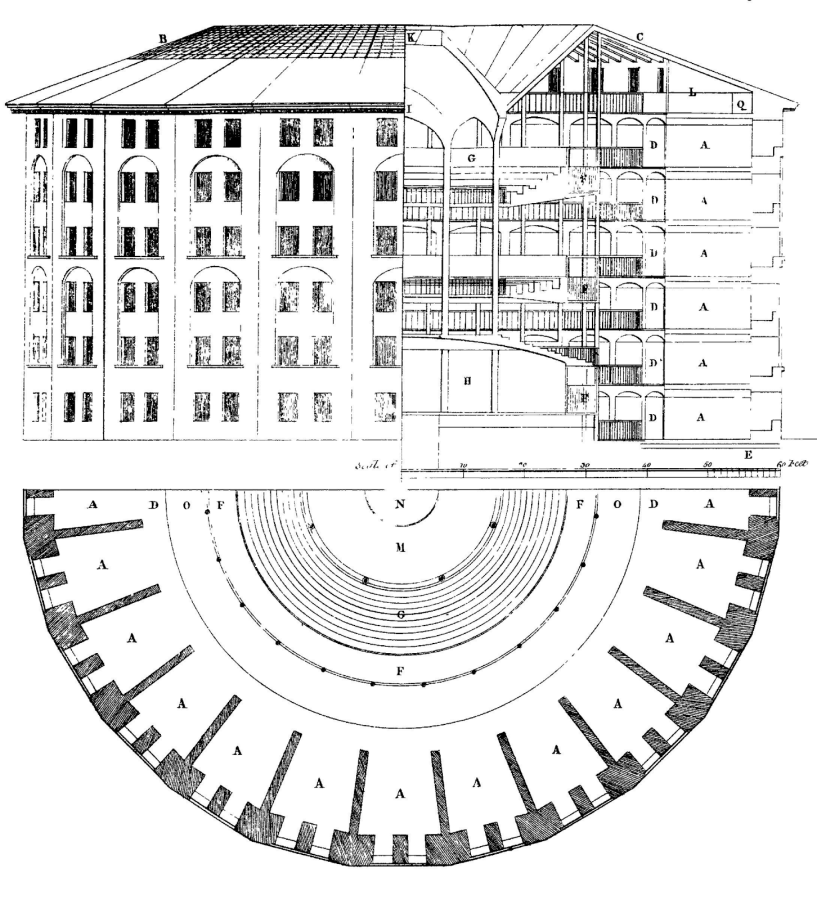

In the late 1700s, philosopher Jeremy Bentham envisioned the panopticon as the ultimate prison. Derived from the Greek word for ‘all-seeing’, Bentham’s design focuses on a central watchtower surrounded by a circle of cells. This formation enables constant observation of all inmates — without them knowing when or if they’re being watched. If the concept sounds familiar, it should. George Orwell drew inspiration from Bentham’s model for his iconic novel, 1984.

The totalitarian state of Oceania is overseen by the omnipresent Big Brother, whose panoptic gaze coerces citizens to comply under the threat of constant scrutiny. As this passage reads: ‘There was no way of knowing whether you were being watched at any given moment […] you had to live in the assumption that every sound you made was overheard, and, except in darkness, every movement scrutinised.’

In 1975, French philosopher Michel Foucault reignited interest in the panopticon through his influential work, Discipline and Punish. Departing from physical conventions, Foucault posed the panopticon as a metaphor for the modalities of power in the modern world. The crucial difference is that here, people are subjected to the panopticon consensually; they autonomously conform to the pervasive gaze of prevailing norms and social institutions. Foucault writes, ‘He who is subjected to a field of visibility, and who knows it, assumes responsibility for the constraints of power.’

Today you don’t need a round building to achieve centralised inspection. CCTV is ubiquitous; Chennai and London are amongst the most densely camera-populated cities in the world, whilst China’s surveillance state boasts over 200 million cameras, analysing over 100 faces per second. 98.8 million of our homes are hooked up to home security systems; a figure that’s set to double by 2027. We’ve not just accepted this proliferation of visibility, but find comfort in it. Herein lies the paradox of the panoptic; we willingly erode our personal privacy for protection, and embrace mass surveillance for state security. But in a landscape of increasingly pervasive, asymmetric scrutiny, we must ask — is the trade worth the cost?

IoT and the impact of emotion-AI integration

It’s been over a decade since the Snowden leaks unveiled the scope of the NSA and GCHQ operations. Our world is irrefutably more panoptic post-Snowden; and yet, despite public outcry, government surveillance practices remain largely unchanged.

We go about our lives aware that Big Brother is watching and, simultaneously, secure in the bubble of our personal browsing. Behind the hazy glow of our screens, the day-to-day illusion of privacy endures. And those lives are increasingly unfolding online; it’s where we work, shop, socialise. Our digital footprints map where we’ve been, what brands we buy, what porn we watch. The truth is that our virtual activities are not only constantly tracked, but commodified; collected by corporations who make mind-boggling amounts of money off the back of our data.

Today, our homes are studded with smart devices. Our machines brew coffee before we’re out of bed and thermostats self-tune; we can turn off the lights or lock the doors remotely. What were once common, household objects now connect to the internet and provide seamless communication between the physical and digital realms. As the Internet of Things (IoT) rapidly evolves, this hyperconnectivity generates an unprecedented amount of personal data — a motherlode that will, by the Law of Averages, likely trickle in government and corporate vaults.

Now imagine if these same objects could reveal how we feel. What if dressing room mirrors could detect our wobbly moments and trigger ads for beauty products? Or if our bedroom items began recommending sleep aid or medication for erectile dysfunction, based on the events of the night prior? The potential misuse by governing bodies is paramount; this data could be used to suppress whistleblowers or curtail protest (similar events have already unfolded in China). Soon every facet of life becomes subject to emotional surveillance. Our emotions — the rawest form of language we use to express ourselves — would be co-opted and normalised under the purview of constant surveillance. In the quest for ultimate convenience and connectivity, could we lose our privacy and personal freedoms for good?

Dystopia hasn’t landed on our doorsteps yet

Open source emotion-detecting AI is still in its infancy. Right now, LAION are looking for volunteers to help build the audio dataset that will train empathic speech synthesis models. They’ve developed a web tool that allows participants to enter a YouTube URL and describe the emotions in the video, using audio annotations and predefined labels.

Critics have been quick to point out numerous concerns. Concerns around regulation are tenfold as of course, once open-source models are released, they may be utilised without safeguards and for corrupt purposes. Serious challenges around accuracy and bias remain. There are no universal markers for how we feel; in an article for MIT, MIT Sloan professor Erik Brynjolfsson explains:

‘Recognizing emotions in an African American face sometimes can be difficult for a machine that’s trained on Caucasian faces. And some of the gestures or voice inflections in one culture may mean something very different in a different culture.’

Emotions are not only complex and nuanced, but an invaluable part of the human condition. In a world of intrepid technological advancement, where do we draw the line? Are we content for what we feel to be reduced to marketing data points in the machine of surveillance capitalism? The development of emotion-detecting AI requires a delicate balance and serious ethical consideration to ensure that, in the pursuit of innovation, we don’t compromise the essence of what makes us human.

Featured image: Matthew Henry / Unsplash