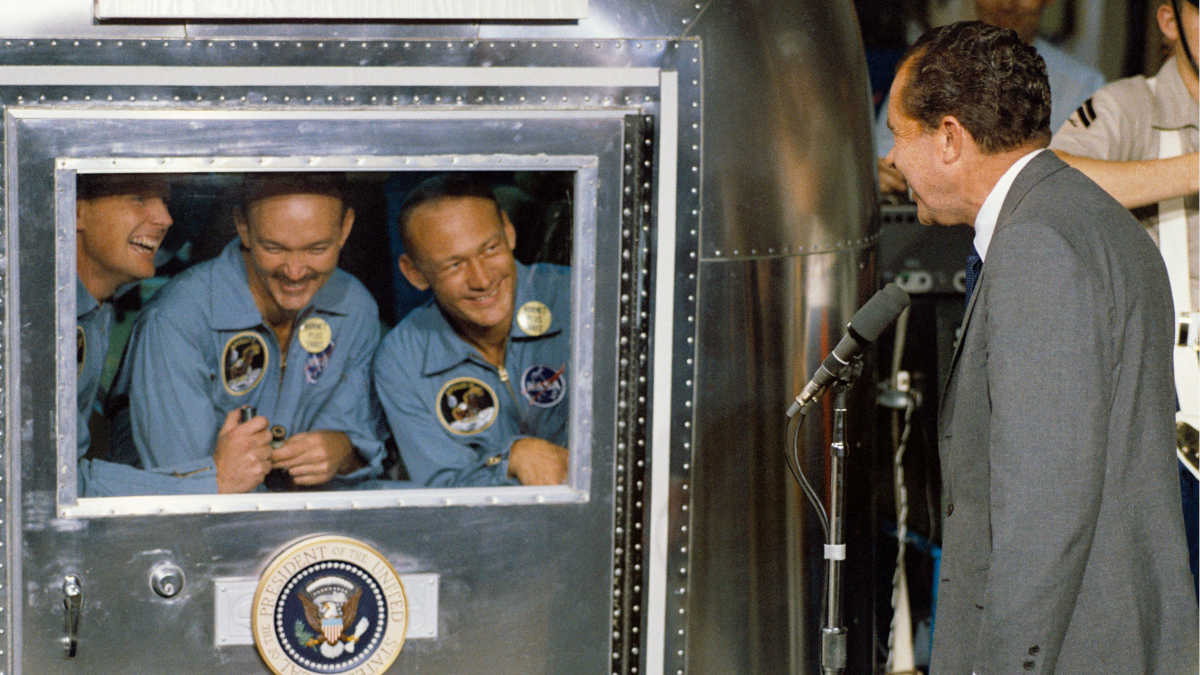

In the winter of 1972, President Nixon embarked on a historic visit to China, with plans for improved relations between the two superpowers.

Meanwhile, halfway round the world at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, psychology graduate Baruch Fischoff set to work. He asked people to assign odds to various possible outcomes of Nixon’s trip — for example that the President would have a surprise meeting with Chairman Mao.

Once Nixon had returned home, Fischoff revisited the participants, and asked them to recall the odds they’d assigned to the outcomes. He found that they greatly overestimated the odds they’d assigned to the actual outcome: their memories had become distorted by the knowledge of what really ended up happening.

This overconfidence that an outcome is as we had predicted is called the hindsight bias.

Hindsight is 20-20

Fischoff went on to explore the concept further, and published what became formative evidence demonstrating the hold that hindsight has over us.

In a 1975 study, he recruited 547 participants and randomly assigned them to one of five groups: one ‘before’ group and four ‘after’ groups.

All groups read a 150-word description of a historical event, such as a battle. The event had four possible outcomes. For example: side A victory, side B victory, military stalemate, and peace settlement.

The ‘before’ group was not told about the event outcome. Each of the ‘after’ groups were told that one of the four outcomes had happened. Apart from that, the event descriptions were identical.

Next, all groups were asked to say which of the outcomes they would have expected at the start of the battle. They assigned each of the four outcomes a probability (with the total adding up to 100%).

And, in keeping with his earlier findings, Fischoff saw that telling participants a certain result had happened meant they were more likely to report that this is what they would have expected. Those in the ‘after’ group were on average 11% more likely to say that the outcome they’d been told about had had a high probability, compared to those in the before group (who had not been told what happened).

Participants were allowing their knowledge to affect their probability estimates. In fact, a small number of the ‘after’ subjects even said that the reported outcome was the only possible outcome — i.e. 100% likely. None in the ‘before’ group said this.

In short, people overestimated what they would have known without the outcome knowledge.

People have a remarkable way of continually re-inventing expectations and framing an outcome as fully expected. This is dangerous as it means we overestimate the predictability of the world.

After all, weren’t your past predictions accurate? So, if they were spot on, won’t your next ones be too? However, hindsight bias suggests that perceived accuracy is based on you adapting your memory to fit the events.

All part of the plan?

Hindsight bias is an issue for anyone who makes plans. Believing the world is predictable breeds overconfidence.

For example, if you think you can predict the stock market, you might riskily concentrate your funds in a handful of shares. Or if you’re sure you know what’ll happen in the broader economy, you might overstretch your finances by taking out a mortgage only affordable on low interest rates.

But it’s not just our personal life that it’s an issue. The same overconfidence can affect our work plans. Imagine you’re about to launch a new product. If you overestimate the predictability of the future, almost by definition you’ll fail to spend enough time thinking about what surprising setbacks might affect you. For example, you might fail to secure a contingency budget to adapt to unforeseen events or a competitor reaction.

Look forward, not back

So, what can you do? Well, simply being aware of the bias is useful, as it gives us a chance to adapt.

However, Gary Klein, a psychologist at MIT, offers one final tactic. He calls it a pre-mortem.

Here, during planning, team members are asked to imagine that the project has gone wrong. They visualise this failure, and work backwards to generate ideas for why this happened. Each member gives a reason from their list until all imagined reasons have been discussed. Afterwards, the team works on ways to strengthen the plan.

It’s subtly different to identifying possible future risks, because it goes a step further, and asks the team to put themselves in the mindset of the failure state.

So, whether it’s politics, your personal life or planning at work, make sure you heed Fischoff’s advice and expect the unexpected.

Astroten’s next workshop on applying behavioural science to marketing will be on November 14 & 16. Details here.

Featured image: History in HD / Unsplash