It’s a Saturday evening and you’re heading out for drinks. You pick your red top to wear — but then hastily return it to the wardrobe: you’re not in the mood for attention tonight.

Well, chances are, you could have got away with the red. Because not as many people will notice you as you think (or hope, depending on your mindset).

You’re not being vain. In overestimating the impact of your appearance, you’re demonstrating a fundamental and systematic bias in human thinking.

All eyes on you?

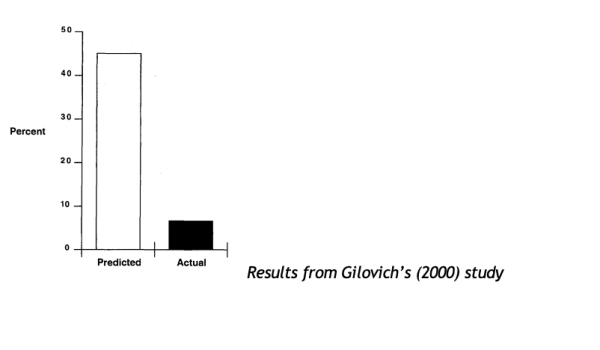

There’s plenty of evidence that we’re not in fact the centres of attention we think we are. One study into what psychologists call the ‘spotlight effect’ was conducted by Thomas Gilovich in 2000 at Cornell University. He recruited 79 participants, who were asked to pick one of three t-shirts to wear, each featuring a famous personality: Bob Marley, Jerry Seinfeld or Martin Luther King, Jr.

Next, participants were escorted into a room of other people, who were already busy filling out a questionnaire. But, after walking into the room, the researcher appeared to change their mind about letting the latecomer join, instead suggesting that perhaps it would be best to wait outside as the others were too far ahead.

The participant was then asked, “How many of the people in the room you were just in would be able to tell me who is on your T-shirt?“.

Participants significantly overestimated the likelihood that observers noticed their T-shirt. In fact, the average estimate made by the participants was a massive six times higher than the actual number.

This suggests that we hugely overestimate the extent to which we are noticed by other people.

And, I’d argue, we do the same with our brands. We assume they’ll be noticed because – like our choice of outfit on a night out — they are top of our minds as marketers.

That’s a problem. It means that too often we’re complacent, jumping straight to information transmission without having first thought about whether we have grabbed our audience’s attention.

Thankfully, behavioural science offers a number of ways to really stand out. Here‘s one.

“Huh?”: the pique effect

To get noticed, you need to jolt your audience out of habitual thought processes. One way to do this is to use what psychologists call the “pique technique”.

The classic study into this was conducted by Michael Santos, Craig Leve and Anthony Pratkanis from the University of California in 1994.

The researchers asked three actors to pose as beggars. Sometimes they stopped passers-by and made a general request, “Can you spare any change?” or “Can you spare a quarter?” In this set up, 22% of people complied.

However, on other occasions they made a far more precise request. They asked, “Can you spare 17 cents?” or “Can you spare 37 cents?” In this scenario, 37% of people contributed.

The authors speculate that the specific question prompts action because it disrupts the autopilot response, which is to ignore a plea for help. The element of surprise breaks that pattern and prompts people to consider more meaningfully how they should react.

Something similar happens with advertising. People are so bombarded with messages that the autopilot response is to assume ads will be irrelevant and therefore they barely process the content.

But you can use the pique effect to disrupt this knee jerk reaction. When planning your marketing, throw in something surprising enough to pique curiosity, and your audience should sit up and listen.

Can you remember the bird in the title of this piece? These studies would predict so.

Which would suggest that if you want to get properly noticed on a night out, it’s going to take more than a red top. Push it further. Maybe feathers?

Featured image: Jonathan J. Castellon / Unsplash