Have you started calling Twitter ‘X’ yet? Me neither

(And I’m not sure what names the team at Alphabet’s highly secretive moonshot company, whose name actually is X, have started calling it. Or what they’re calling Elon.) Will the name change turn out to be a mistake? Or is it more Elon’s genius in disguise? And what’s changed since the days when a rose would smell as sweet whatever it was called?

Do names now mean more than they used to? Or are business owners just taking an easy way out and thinking that a name change will do the rebranding work for them?

Three things can change to make a rebrand name change a good idea: the best businesses outgrow their initial product line. Facebook’s change to Meta made sense, even if you were being cynical and assuming it was to deflect the negative attention at the time on the site. Well, perhaps, especially if you were being cynical.

Alphabet (disclosure: a client of my verbal branding consultancy) was a great name to reflect the continuing ambition to be all things far beyond the search engine.

This kind of name change is something that some celebrities have done well. I remember how the audacity of Prince changing his name to an unpronounceable symbol perfectly matched the don’t-give-a-damn of his music creations. And it matched his intent to make a different kind of music.

I’ve lost count of how many times Sean Combs has changed his name, but I think it’s about 8 or 9. His latest change included the middle name ‘Love’ and more than a superficial publicity stunt, it represented something to him and he hoped to the outside world. ‘Love is a mission.’

But a brand isn’t an absolute thing. It’s something that exists in relation to a changing world

And when the world changes, a brand can quickly become ‘debranded’. I don’t mean it’s suddenly lacking in external symbols of meaning, but the world can move and leave a business with those symbols representing (or revealing) something entirely different.

That’s when the second name change can help make the business seem more fit for the changed world. Hopefully in a way that signals as much to the people inside the company walls as outside, that things need to change.

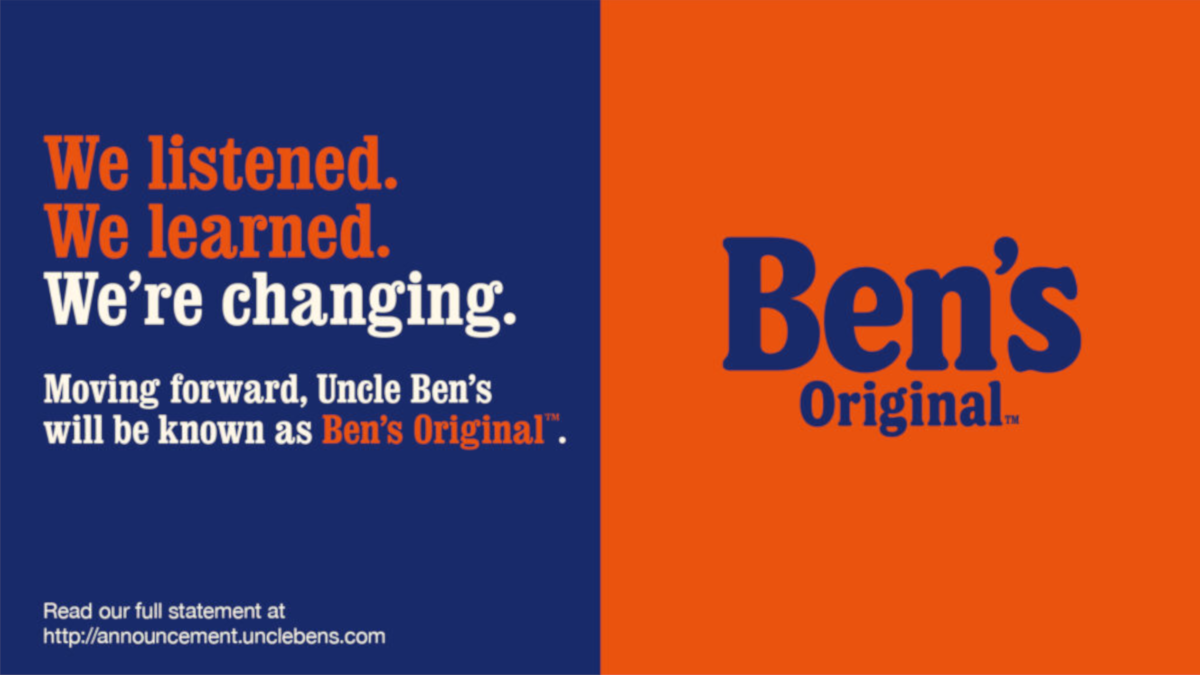

Uncle Ben’s rice? Its new name is Ben’s Original.

The changes weren’t confined to large companies. The Captain Cook Hotel in Dunedin, New Zealand, changed its name to ‘the Dive’ reflecting (finally) the controversial legacy of the explorer among the Māori. Some large organisations missed the memo entirely. London’s Imperial College removed the Latin motto under its name, but kept the name just as it was.

Of course, it wasn’t just names which changed. The curvy bottle of Mrs Butterworth’s was remodelled to suggest a less obviously ‘mammy’ racist shaping. And the ‘tomahawk chop’ used by fans to celebrate the Atlanta Braves’ successes? Definitely discouraged.

And even when there had been no connotation with out-of-date racist intent, the world changed and debranded a product. The Fred Perry clothing brand (disclosure: also a client of mine) announced they were stopping their Black/yellow/Yellow Twin tipping on their shirts, after they were adopted by the Proud Boys.

The third reason for a name change seems to be pure whimsy. Or at least, a superficial change of branding rather than a change of the fundamental brand proposition. After I left agencies I was writing screenplays for a while (don’t ask), basing myself in a London movie production company. One morning, I overheard the explosions of the producer next door. He’d opened his laptop and came face to face with the long exchange of emails that had happened overnight; from Jennifer Lopez’s team demanding that all the posters already printed all around the world should be scrapped, because she now wanted to be known as J-Lo. Jennifer Lopez/J-Lo? I respect everyone’s right to be called whatever they want, but to a lot of people the difference between the personas of J-Lo and Jennifer Lopez weren’t obvious.

Language is the fastest, easiest, (and sometimes, cheapest) part of a brand to change, to make it fit into the changed world

Why? Because we’re the language animal, using language from the very beginning to share ideas and build relationships, and so outperform our rivals.

We use language everywhere, all the time, in our brands. From the obvious external communications to the equally hard-working customer service letters, CEO speeches and signage around the building.

And of course, subtle ways to promote features of our products (Tesla’s ‘Ludicrous’ speed option, for example).

And Twitter/X? So far, I can’t see the difference since the rebrand. I think Elon’s genius of removing a few people and at the same time almost $30bn of value (two-thirds of its value since he bought the company) is perhaps ‘yet to play out’.

Chris West runs Verbal Identity, the UK verbal branding consultancy. www.verbalidentity.com You can read more from Chris on LinkedIn.