We had the pleasure to meet Steve Harrison during the FixFest, this year’s copy event hosted by Glenn Fisher and Nick O’Connor. He’s recognized as one of the UK’s leading advertisers, with Campaign dubbing him ‘the greatest direct marketing creative of his generation.‘ Steve authored, among others, How to do better creative work, which once traded on Amazon at £3,500 a copy.

Steve, you completed a doctoral thesis on American Society, Cinema, and Television before entering the advertising industry. How did your academic background influence your approach to advertising and copywriting?

Writing a 140,000 word thesis is good training. First it teaches you to organise your thoughts, do your research, devise your proposition and support it with facts. It also gives you self-discipline. For several years you are working alone. You have to sustain yourself through long periods when there’s no feedback other than the voice inside your head which says ‘you’re wasting your life.’ But finally it gives you some confidence in your own ability to synthesise information and create something original. And it toughens you up! Doing a few all nighters for an agency pitch is a piece of cake after what you’ve been through. Not, I hasten to add, that any of this impressed the recruitment consultant I met when I moved to London having gained my PhD. He looked at this 29 year old loser and dismissed me as ‘unmarketable.’

You started your advertising career at Ogilvy & Mather and later founded Harrison Troughton Wunderman. Can you share some key moments or experiences that shaped your journey from researcher to agency founder?

I was working as a researcher/librarian at O&M Direct. I’d done lots of jobs before — bar work, gardening, labouring and even had my own sandwich making business but this was the first salaried job I’d had. And I was determined, at the age of 29, to keep it. So I made sure I worked harder than anyone else and was always useful to my much more important and productive colleagues.

I enjoyed writing research docs when the agency was pitching and the boss of the agency, Drayton Bird, liked them, too. One day he came down to my office and asked if I wanted to be a writer. I said ‘yes, please‘ and he said he’d give me 6 months. If I wasn’t making him any money by then, I’d be out. I was then the 30 year old trainee copywriter in the creative dept. While my younger colleagues had gone to college to learn about advertising, I had the advantage of having lived a little — and was able to empathise more with the people I was writing to. All I needed to do was read every book on advertising that I could get my hands on — and I was quickly on or above the same level as my peers.

You’ve won several Cannes Lions awards, making you one of the most decorated creative directors. What do you believe sets your work apart and has contributed to your success in the industry?

I was steeped in the creative aspect of my discipline. If you’ll pardon the term, I had the gestalt by the bollocks. I knew what was good work and what was bad. I knew what had been done before and what had never been done before. And, if it was on brief, directed my colleagues to the latter.

I also understood the importance of the creative brief and insisted that our suits knew how to write them. My partner, Martin Troughton, and I put great emphasis on training, so everyone knew what was expected of them — and how to do their jobs properly.

Could you tell us about some of the most memorable campaigns you’ve worked on throughout your career? And the ones that inspired you the most?

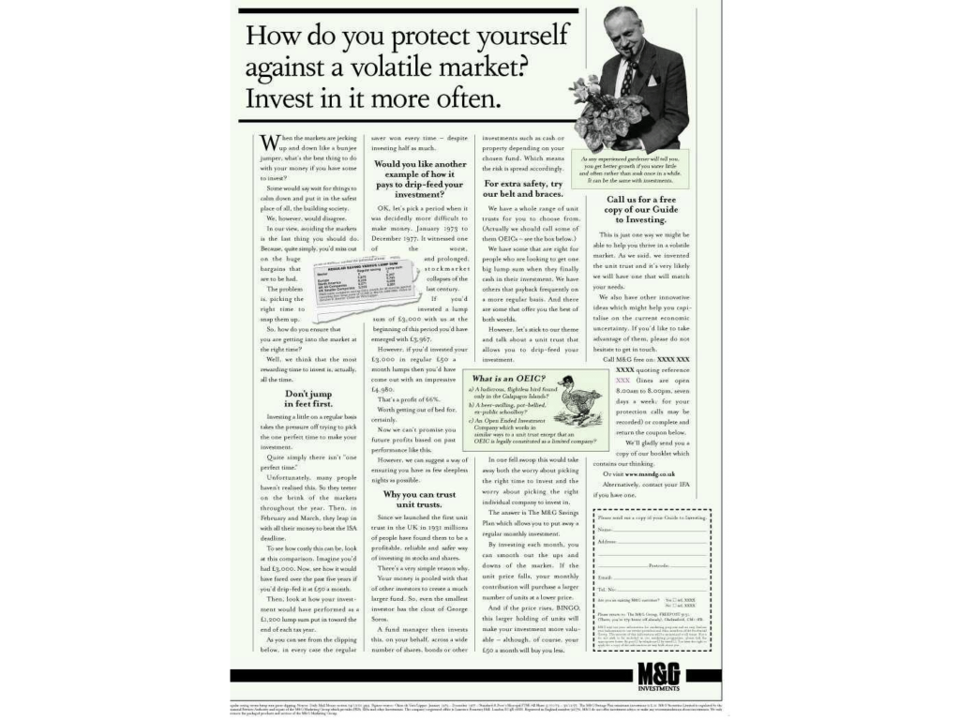

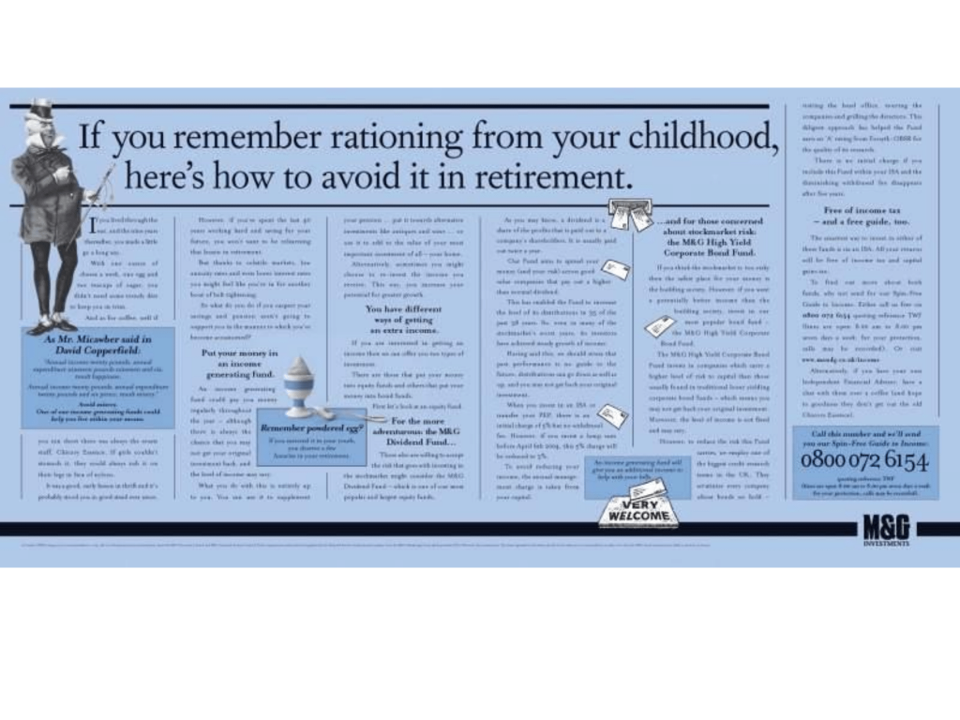

M&G Investments was probably the best work our agency did. It was a long copy press and underground poster campaign aimed at the over 60s (who, back then, held 74% of the nation’s disposable income). It ran for six years and won at both Cannes for creativity and IPA for effectiveness. I think it is one of the three best financial services ad campaigns our industry has produced.

Your book ‘Changing the World is the only fit work for a grown man’ (and your panel at the FixFest) explores the life of advertising pioneer Howard Gossage. What drew you to Gossage’s work, and what lessons can modern advertisers learn from his legacy?

I discovered Gossage in 1988 and he was an inspiration thereafter. He was the first to realise that you must involve the news media in your media strategy. By that I mean, he would write an ad aimed at getting the newspapers, radio and tv to notice and amplify its message.

My agency did that for our clients long before it became the norm. Gossage also realised that it was his job to make his clients famous — not just amongst the target audience but amongst the general public. Fame is the engine of marketing success — and Gossage knew that. He also knew that you sell more stuff if people like you — and Gossage wrote ads that were, in and of themselves, interesting and enjoyable. Which is a lesson that our shouty, po-faced industry needs to learn.

You mentioned helping people and businesses to produce better creativities and copy, including partnering with a start-up in Vietnam that sold for $20m. Could you share a success story or key strategies you implemented to achieve such results?

I’ve worked with everyone from NATO (SHAPE StratComs, Rome) to UCLAN (University of Central Lancashire, Preston). My basic message is that you have to ask your client (or yourself) these two questions: what is the prospect’s problem and how does the product/service/idea you are selling solve it for them? Regardless of whether you’re writing an email or positioning a brand, if you can’t answer those two questions, don’t bother advertising. Indeed, ask yourself why you’re in business?

Your latest book, Can’t Sell Won’t Sell, has garnered praise for its analysis of the advertising industry. Can you provide a brief overview of the main challenges you’ve identified in modern advertising and your proposed solutions?

The advertising industry has lost interest in selling. You can see this from the work that the industry regards as exemplary. In the past five years over 80% of Grand Prix at Cannes have gone to social purpose driven work. Work that actually aims at selling things — ie work with a commercial purpose — has been marginalised. It is the same at D&AD, The One Show and all the major awards. And I would venture that our politics are to blame. Our industry leans very heavily to the Left — but not the old Left of working class solidarity and wealth redistribution but culturally to the Left.

And its most vocal and influential members, the activists and careerists, see their three evils — racism, sexism and homophobia — as having their root causes in capitalism. If you add the climate crisis to the rap sheet then you understand why a politically progressive adland is no longer comfortable stoking capitalism’s engine of growth and consumption. So, we’re not selling. Nope. Instead, we have a new raison d’etre: we’re saving the world. Problem is the vast majority of the world doesn’t want saving — well not by the ad industry anyway. Indeed there’s a fundamental disconnect between the elite, university educated, metropolitan and privileged clique who work in adland and the culturally conservative mainstream.

And perhaps the main question I ask is this: as our clients and customers struggle with inflation and a cost of living crisis, will advertising rediscover its commercial purpose and help them revive the economy? Or will adland double down on social purpose and the groupthink that’s suffocating a once brilliantly creative industry and forcing it to the margins of business and cultural life?

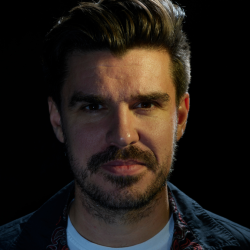

Featured image: Steve Harrison, Copywriter and maker of better creative work