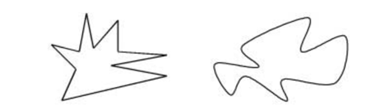

Take a look at these two shapes.

Now imagine they have names: one of them is a ‘bouba’. The other is a ‘kiki’. Which do you think is which? If you’re like the participants in a well-known 2001 study, you’ll have picked ‘bouba’ for the rounded shape and ‘kiki’ for the prickly looking one.

The study was conducted by Vilayanur Ramachandran and Edward Hubbard from the University of California. They recruited American and Tamil speakers and asked the same question, although verbally rather than in writing. The results were very clear — 95% thought the rounded shape was likely to be a ‘bouba’. Only 5% considered it a ‘kiki’. Which shows that we imbue certain word sounds with shapes. It’s come to be known as the bouba-kiki effect. The authors suggest it might be down to a connection between the way our mouths move — kiki needs a sharp movement of the tongue, bouba requires your mouth to make an open, rounded shape.

It’s a well-founded observation, with the same results seen almost 100 years ago in a 1929 study by Wolfgang Köhler. In this case, he tested two shapes with the names ‘maluma’ and ‘takete’. But the bouba-kiki effect seems to go beyond a link between words and shapes.

And this is where it becomes more interesting for brands. Because there’s evidence that we connect more than just sound and form — we attach meaning too. An example of this comes from a study by Charles Spence, who explored how various food and drink items corresponded with shapes or nonsense sounds. He found that the word ‘bouba’, as well as rounded shapes, were more commonly associated with ‘softer’ food options: still water, caramel milk chocolates and Brie. Whereas the word kiki, and angular shapes, were associated with ‘sharper’ foodstuffs: sparkling water, cranberry juice and crunchy chocolates.

What does this mean for brands?

The evidence suggests that your brand name, as well as the words you choose to discuss your brand, will carry meaning and elicit a response simply through their sound and shape. So, it’s worth making sure that the sound of your name corresponds to the values you want to communicate.

Think of the word Google — friendly or unfriendly? Certainly, it has always been designed to be an easy, accessible experience. Or Boots, a chemist that aims to be supportive and helpful.

Some sharper-sounding kiki-esque brand examples include Nike — associated with speed and precision, Skittles — sweets with a crisp fruity flavour, or Skype — an efficient business-focused offering. In each case, the sound of the name seems to align with the brand.

Music to the mind

So, it appears that our senses are connected: visuals are associated with sound, and both can carry meaning. And there’s evidence that when it comes to sound, it’s not just words that matter. Music is important too.

A number of studies have found that playing classical music changes our perceptions. For one such study, in 2003, Adrian North at Leicester University ran an experiment in a high-end restaurant over a period of 18 nights. Some evenings the restaurant played no music; on others, they played classical or pop. The results showed that with no ambient music, customers spent on average £30. With pop music, they spent slightly less, at £29.

However, when the background sound was gentle classical music, the average total spend per customer rose to around £33. This was a statistically significant 10% increase compared to evenings without music, and 14% higher than the pop music backdrop.

Further studies have shown that this effect doesn’t just apply to higher-end eating establishments. A few years earlier in 1998, Adrian North and his colleague uncovered similar findings in a student cafeteria.

Some days featured no music. On others, there was ambient classical, pop or easy-listening music. You can see the results below.

| Music | Daily sales total |

| None | £802 |

| Easy listening or pop | £898 |

| Pop | £1,299 |

| Classical | £1,324 |

The results show that classical music accounted for a huge uplift in spend — 65% more compared to the days when no music played in the canteen.

Classical music seems to boost spending, perhaps because we associate it with luxury and sophistication.

It’s not just restaurants who should take heed. Whatever your sector, you can harness the innate connections we have with classical music to help elevate your brand — consider how British Airways used Delibes’ flower duet to subtly improve their perceptions. Music will create an instant mood and the right kinds will even boost customers’ willingness to spend money.

These sound like findings that all brands should listen to.

Featured image: Mick Haupt / Unsplash