Picture the scene: it’s 2003 and eight Creative Directors are sitting in a windowless basement room somewhere in Cannes. They have agreed to spend three days there, judging all the commercials that have been entered that year. Outside, the sun is shining, and many of their colleagues are now several bottles of rosé into a very long lunch.

Those creative directors have taken on this task for the honour and prestige, but by day two they are starting to lose the will to live. Unlike awards judging today, they can’t just skip ahead when they get bored. They have to watch every second of every ad. One of the few things that can break the monotony is a funny ad, especially if it’s funny enough to elicit a few actual laughs. Laughter is communication, a signal that says ‘I like this’, so when you hear it, you feel a bit more like laughing yourself, especially in a dark, sweaty room in Cannes.

And that’s how funny ads once held an advantage over less funny ones…

They made the judging process less annoying, and they provided an outward signal of approval, which people felt a little more obliged to agree with. In addition, humour, especially visual humour, travels well, so there would be less need for the Swedish juror to explain the meaning of an ad to someone from Brazil. But that’s not how ads are judged today.

These days you do most (or often all) of the judging alone on your laptop, then you might discuss your opinions with your international colleagues on a Zoom call three weeks later. In addition, there’s now a two-minute case study for most commercials, something which reduces the will to live, and reduces the chances of spontaneously finding something funny.

The communication effect of laughter becomes irrelevant, as there is no one nearby to join in. So you have to wonder if anyone else got the joke. Then you have to remember how funny you found that ad, and try to stand up for it on that awkward Zoom call. So ‘funny’ now has less power than it used to, and the mandatory two-minute case study is much better suited to something serious and purposeful. The knock-on effect of that, whether consciously or otherwise, is that people who are trying to win awards (that’s pretty much every creative, agency and network on the planet) start to lean in the direction of what will get a more sympathetic hearing from a jury.

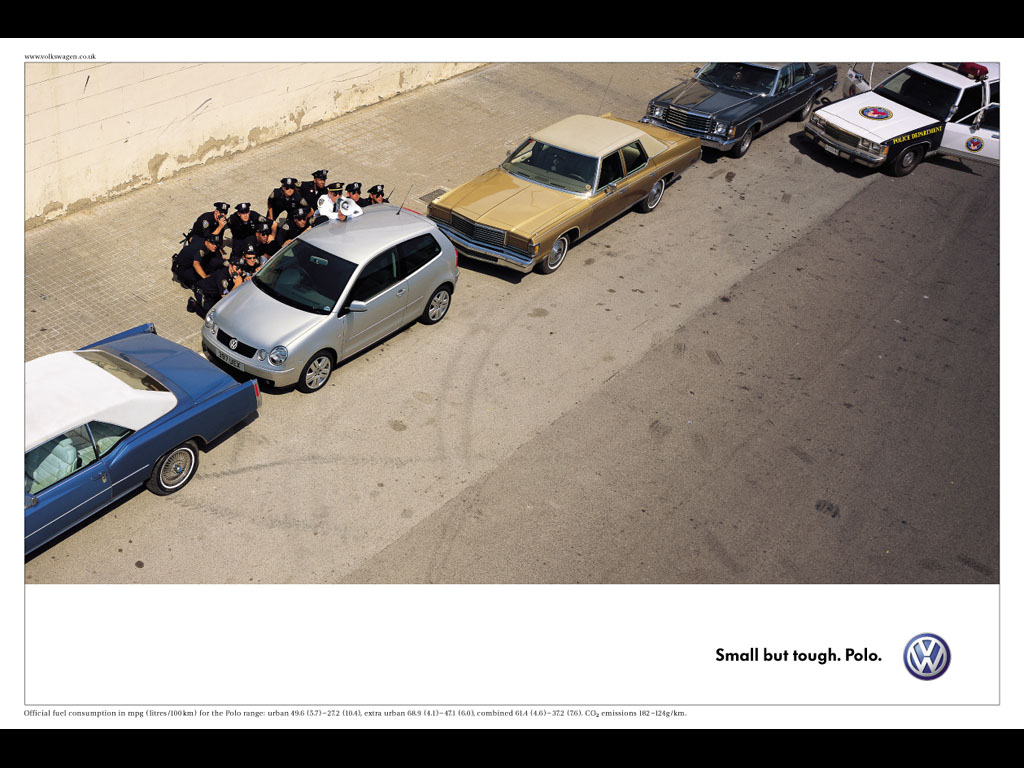

In the early 2000s juries became more international, so creatives started to created ‘prosters’ — press ads that acted like posters (see below), with one clean, simple visual and a logo, and no confusing words to trip up a juror from a country that might not speak your language.

Now that it’s easier for serious/non-funny ads to win awards, creatives are more inclined towards creating ads like that. That means their heads are in the space of ‘what heart-warming purpose-based initiative can I think of for this?’, and not ‘maybe I should write a few gags’.

They want awards, and the money and promotions that awards lead to, so why make that job more difficult? Actions have consequences, and although the change of judging process, accelerated by the pandemic, was never intended to affect the type of ads we produce, I believe it did. Or, at least, I believe it helped push that process along.

To be clear, lots of factors have helped to push funny ads out of the current vogue…

The rise of the 60-second heart-warming John Lewis-type commercial; the doom and gloom of the cost of living crisis; the fear of cancel culture that comes from making fun of anything; the deterioration of the very specific set of skills that turns funny scripts into funny ads. That said, now would surely be the best time to offer the world a bit of humour. The first job of advertising is to be noticed, something that is much more likely to happen if you do something different to everyone else.

So if funny is out of fashion, a savvy marketer should lean heavily in that direction. If creatives or agencies are less inclined towards generating laughs then look elsewhere. Social media and YouTube are full of people who can bring the funny, often inexpensively, and usually in the kind of shorter time frames that advertisers tend to use. Humour is a fundamental human characteristic, jam-packed with positive connotations. That means it should be a strong part of any marketer’s arsenal, and if agencies don’t want to supply it simply because it’s no longer the bullseye for winning awards, maybe that’s the sign that it’s due for a comeback.

Featured image: ‘proster’ for the 2001 Freelander Land Rover