Most people lie…

You might not believe me — and if that first sentence is true then you’d be right to be suspicious. But there’s robust experimental evidence that supports my claim. For example, Robert Feldman, a psychologist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst ran a study into the frequency of lying in 2002.

He asked students to briefly chat with a stranger. Unbeknown to the participants Feldman was secretly recording their conversation. Later, the psychologist re-contacted the students and asked them to watch their tapes and note down the number of lies they’d told.

The results are disturbing. More than 60 percent of participants lied at least once during the 10-minute conversation, and the average number of lies was almost three. Staggeringly, one person even managed to cram in 12 lies during the brief chat. (Unfortunately, Feldman doesn’t say if that person went on to a career in marketing.)

Why does it matter?

So, we tell a few porky pies from time to time. Why does this matter to you? Well, it’s important because so many brands treat customers claims as if they were honest. Think of all those surveys and focus groups marketers rely on to make decisions. You can bet a fair few of those answers are made up.

So, first up start being more sceptical about claimed data. You might want to follow the attitude of The Times foreign editor, Louis Heren:

When a politician tells you something in confidence, always ask yourself, ‘Why is this lying bastard lying to me‘

But beyond a healthy dose of scepticism, what else can you do? I suggest you take solace in the fact that lying isn’t new. People have always been economical with the truth. More than 100 years ago Mark Twain observed of his fellow Americans:

Everybody lies… every day, every hour, awake, asleep, in his dreams, in his joy, in his mourning. If he keeps his tongue still his hands, his feet, his eyes, his attitude will convey deception

And since lying isn’t new, people have already discovered robust tactics to uncover the truth behind what really influences people.

Observe, don’t ask

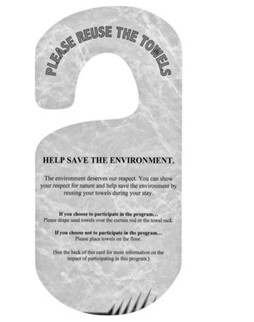

This is fundamental to the experimental method: scientists gathering evidence don’t simply ask if the red pill or the white pill worked best. They conduct a trial and observe the results. When possible, it’s the approach taken by psychology researchers too. Take, for example, Robert Cialdini’s classic experiment into hotel towel re-use. He tested various in-room signs to encourage people to use their towels again, rather than request fresh ones. Some messages emphasised that most guests re-used theirs (thereby harnessing social proof); others focused on the environmental benefits.

Cialdini randomly allocated the messages to different rooms and then observed what happened in practice — circumventing the tricky issue of participants reporting what they think the ‘right answer’ might be. He found that people were 26% more likely to re-use their towels if they were exposed to the social proof message.

In a follow-up, Cialdini asked another group of participants (via a survey) what they would do when faced with different towel messages. Of course, they claimed the environmental message would be most influential. Further evidence that, if you ask, your answer may not reflect the truth of the situation.

Cialdini’s hotel study is an example of a field experiment, and you can use this approach too. Each group you recruit should be exposed to a different stimulus (rather than a single group being exposed to multiple stimuli and comparing them). That way you’re more likely to get meaningful results.

What would others do?

That’s not the only tactic at your disposal. Psychologists suggest another way to get to the truth — ask participants how they think other people would behave. Because it seems that we’re pretty spot on at guessing the actions of others, even if we can’t quite get it right for ourselves.

Evidence for this comes from a 2000 study by Nicholas Eppley at the University of Chicago and David Dunning at Cornell.

A few weeks before a charity sale of flowers, the researchers asked 251 students to predict whether they would buy one. Participants were also asked to predict what their peers would buy.

83% of students said they would be charitable and buy a flower. But they guessed that only 56% of their peers would.

A few days after the fundraiser, the researchers followed up on what participants had done. It turned out that only 43% had bought a flower. They had significantly overestimated their own generosity — but their predictions of others’ actions were closer to reality. (They had still overestimated, but to a much smaller degree.)

This suggests that you may get closer to the truth if you ask participants to comment on other people, rather than themselves. It might be worth a try in your next survey.

Lying is natural and helps us avoid social disasters. As Mark Twain so aptly puts it, ‘None of us could live with a habitual truth-teller; but thank goodness none of us has to.‘

And whether lying is on the rise or not, we have to deal with it daily. Thankfully, when you need to bypass the well-meaning untruths of your customers, psychology offers a few ways to uncover the full picture.

Featured image: The Polygraph / Wikimedia