“May you live in interesting times” — as that old Chinese curse goes

We are all cursed. Apparently. Everyone thinks they’re living in unique times. Every one of us thinks that the changes that are happening now are absolutely the most ch-ch-ch-ch-changey changes that have ever happened in the history of ch-ch-ch-ch-changes.

But are they? Or do we just all suffer from that secret exceptionalist narrative that convinces us that what is happening to us now must be the most exceptional thing that has ever happened?

For starters, those wonderful folks at BBH Labs released some data last year that showed that virtually all things relating to consumer attitudes and behaviours haven’t really changed an iota over the last twenty years — despite media hype and Twitter-based hysteria. Dean Matthewson and Harry Guild did some hypnotically brilliant work to show that “change sells” for marketers, hence why it’s fashionable to sell it, but that attitudes to pretty much everything in society haven’t (and don’t) really change at all.

So why do we think that everything is changing so much all the time, and why do we obsess over it?

It is natural for humans to think that things change. We are programmed from an evolutionary perspective to only notice new things. It starts with a principle called the Von Restorff Effect. Back in the days of the savannah it was vital for us to be able to focus on the many and varied threats that could kill us, so the brain evolved to edit out what it thinks it has seen before and only notices the noticeably different. So, we are physiologically hard-wired to obsess about change. The second thing is called Hedonic Adaptation. This scientific principle builds on Von Restorff and shows that we automatically assimilate every positive change as ‘normal’ and only notice the negative. Again, it was a survival mechanism. It’s why we moan about the price or speed of inflight wifi rather marvelling that the internet, or the wireless internet, or wireless internet IN THE SKY exists at all. We only see the bad bits of change. I’ll come back to this, too!

My own experience of this is through the lens of technology changes over the last twenty-five years. This is because it is technological changes — such as social media, mobile, the metaverse — that tend to dominate discussions over what is changing; for good, but mostly when it comes to the media, for worse. The vast majority (80%) of the coverage of technology in the press comes at the topic from a negative slant.

I started working on technology clients in 1997

I was lucky that my first large client was IBM, who even then spent 10% of their budget online on banners and buttons (unheard of back then). My first campaign for them on Lotus Notes was called “Work the Web” featuring Dennis Leary, and therefore I was exposed to the potential of the web very early on. Part of this meant I was put on a four-person committee at Ogilvy called the ‘Work the Web Committee’ to convince the sceptical WPP network that the internet was going to catch on. This was before there was an Ogilvy Interactive, before Google, before YouTube — hell, it was before Tim Berners-Lee was even a Sir (we ran a brilliant campaign to get him his knighthood btw — ask Rory Sutherland about it, if you don’t believe me) It was nearly a decade before any of us were to hear of Facebook or Twitter.

I then went through the emergence of the mass internet and the first dotcom bubble, boom and bust. I was the Head of Strategy at BT when we launched broadband in the UK in 2002, and as things like WAP (What A Palaver) and the mobile internet started to emerge. I then ran strategy on Sony Ericsson, Nokia and Three.co.uk as the world of social media started to take off 2007-2012, and since have watched with professional and personal interest as VR, AR and the metaverse has started to enter the mainstream. At each stage I have been deluged with increasingly panicked articles about the end of days that have been supposedly heralded by the arrival (and occasional subsequent disappearance) of all these things.

What have I noticed?

Well, largely that the arguments, impacts and even the language used has been similar at each stage of the emergence/adoption of technologies. And to be honest, the fundamentals of human behaviour and motivations haven’t really changed at all. Technology amplifies or augments existing traits or behaviours; it doesn’t create them. I have always been asked to write articles like this one on the huge seismic unique changes of whatever huge seismic unique changes are happening this week.

I’d like to recommend three books that have stuck with me over these times that help support the argument better than I could.

Douglas Rushkoff (1997) — Children of Chaos: I first read this as a wide-eyed Account Manager in the late 90s. It basically covers off all the potential negative impacts of the WWW on children and teenagers. The oldest teenager that it referenced in 1997 would now be 44 years old. It honestly could have been written yesterday. Its thesis about technological change is the same as the articles being published now about Twitch, Meta, and the ‘screenager’. It’s now 25 years old.

Tim Guest (2007) — Second Lives: A superb romp through the impact of Second Life (remember that?) on society at all levels. If you replaced the words “Second Life” with the word “metaverse” it would be identical to 99% of the articles I have read about the second topic in the last 18 months. It’s almost eerily uncanny.

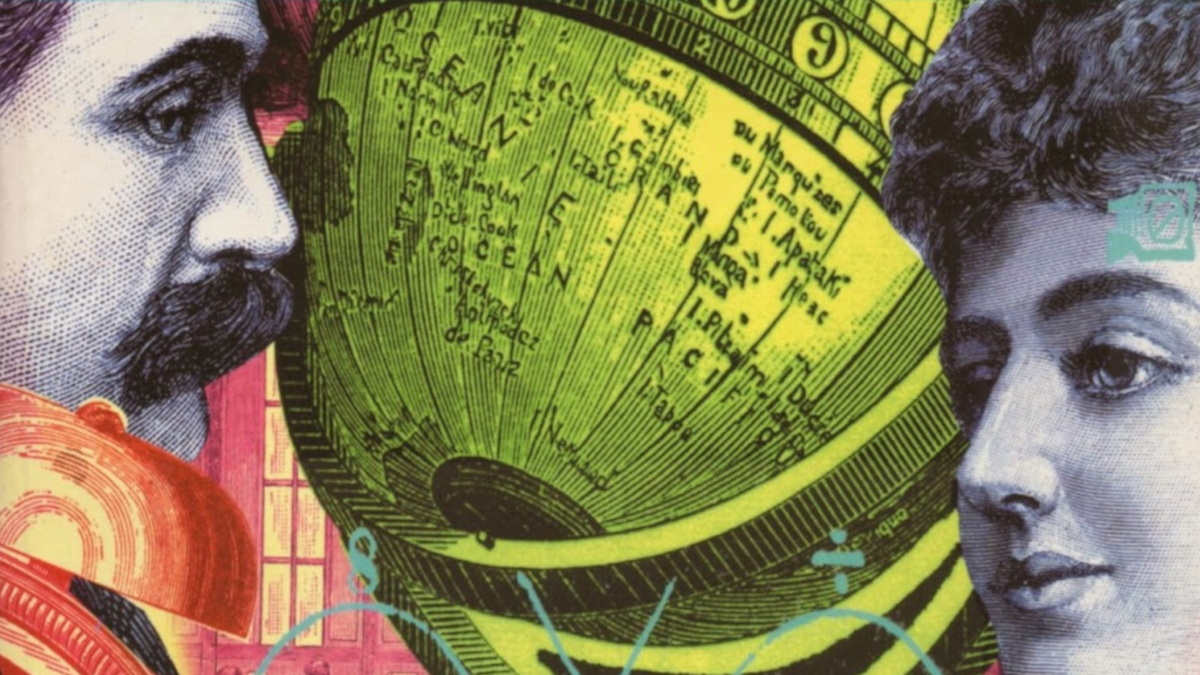

Tom Standage (1999) — The Victorian Internet: This one is the real pearler. It compares the language used around the emergence of the telegraph in the mid 19th century to the emergence of the WWW in the last 90s. It proves that the hype, hysteria and even the words used (“it’s a web of ideas”) was identical back then as it is now — plus ca change.

I’m not saying that things don’t change but they don’t change as fast or as extremely or as permanently as people think they do. Technology changes, humans don’t. Science changes, humans don’t. We just think we do because of all the reasons I outlined earlier. We’re physiologically hard-wired to notice and amplify change, so we can’t help ourselves. The core motivators and drivers of human behaviour are pretty constant — writing The Creative Nudge taught me that.

I’ll leave it to Bill Bernbach to sum it up. He’s a bit better at writing than me:

“Human nature hasn’t changed for a million years. It won’t even change in the next million years. Only the superficial things have changed. It is fashionable to talk about the changing man. A communicator must be concerned with the unchanging man with his obsessive drive to survive, to be admired, to succeed, to love, to take care of his own.”

Featured image: The Victorian Internet, by Tom Standage