Cad, bounder, blaggard, scallywag, knave, rogue, scoundrel or villain?

All these supposed synonyms have slightly different meanings that encode social values. Whilst it is a myth that only the English language is sufficiently broad to require a thesaurus, it is a very accommodating language. Due to invasions and exchanges both domestic and colonial, English has a vast number of linguistic immigrants, and therefore synonyms, in its vocabulary.

Cad and blaggard originally meant someone who was rude to, or in front of, women. Bounders are out of bounds, a person of low morals who acts above their station. Knaves started out as male servants or someone of low birth but, as the mercantile classes rose to power, it became a term for someone who was deceitful and only concerned with their own material gain. Scallywag connotes rule breaking by someone who is nonetheless very likeable and rogue plays in this space too. A true scoundrel is without honor or virtue. A villain is wholly evil and mostly appears as a one-dimensional foil in fiction. So whilst they might seem similar on the surface, rogues and scoundrels are subtly different. Rogues can be a necessary corrective to an oppressive status quo, whereas scoundrels happily profiteer from dysfunction.

A rogue is often conflated with a scoundrel but it might also refer to someone playfully mischievous or a scamp (not the advertising industry sketch of an idea). It might equally be one who simply doesn’t behave in the accepted way, or challenges those norms, moving towards rebel or revolutionary, which we have generally positive associations with, thanks to Star Wars and the history of democracy. Both rogues and scoundrels exist against a backdrop of normative behaviour, what is considered moral in their society. Despite Thatcher’s protestations that there was “no such thing as society,” there of course is a set of values and behaviours that are incentivized and another set that are not supported or actively punished. ‘Strong man’ politicians perform as rogues so that they might be better scoundrels.

We are long past the techno-utopian era where corporations might enshrine “Don’t be Evil” in their founding documents (Google removed it from their code of conduct in 2018). An upcoming book promising to help readers “rethink marketing for the attention economy” is entitled “Just Evil Enough”. Perhaps now truly is a time for rogues and scoundrels, but which will you be?

A rogue or a scoundrel

Scoundrels are those who profit from systemic injustice, war and pestilence to fill their own pockets with no concern for the endless externalities. Rogues accept the moral compromises of their time to survive but don’t accept that things must be this way and push to change them. Rogues are creative. The ‘Trickster Makes the World’, in Lewis Hyde’s classic book, because “the trickster is anybody who’s a bit of an outsider. They’re the ones who make change. They’re not thinking about making change; they’re almost doing it in a selfish way. But because they’re working outside the rules, they change the rules. Everything around them is always new, everything is an opportunity. It’s important to honor mischief-making, in a constructive and creative way, because that’s how we effect change. And it’s so important that we figure out our inner mischief maker. That’s the creative part of us. And everybody’s capable of it.”

Analysts at Contagious dubbed “Mischief Managed” one of the trends emerging from Cannes this year. Creative activists protested the award show and more recently outside the offices of WPP and Edelman, distributing pamphlets entitled “The Brief Sabotage Handbook” (inspired, one assumes, by the classic OSS/CIA “Simple Sabotage Field Manual” which detailed how allied office workers in occupied countries could sabotage a workplace without getting hauled up by the Nazis). The Creative Communication Workers Union has been set up in the UK to help talent negotiate for better wages, hours and environments.

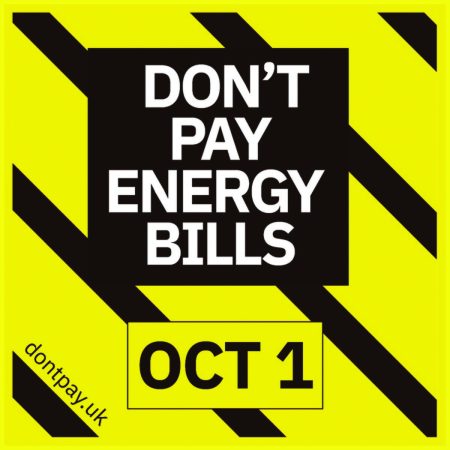

A national movement is growing in the UK, called Don’t Pay UK, is looking to highlight the impossibility many will face paying energy bills this winter and has been condemned by the government, who instead have decided to borrow £100 billion to pay to the power companies so they can maintain profits whilst people in the country go hungry (1 in 10 have skipped eating for a day because they can’t afford it {Food Foundation}) or use food banks to survive (“Between 2008/09 and 2020/21, the number of food bank users increased in every year, from just under 26,000 to more than 2.56 million”.)

Scoundrel brands leverage their power in the market to extract rents and change laws to suit themselves while pushing the cost of externalities, like polluted water or recycling, back on to their customers or the governments (and thus taxpayers) that provide them with favourable tax environments. Rogue brands challenge the status quo, provide better customer experiences, stand up for their employees and invest in infrastructure and innovation rather than funnelling all their profits to shareholders through buybacks and dividends. The decline in the trust in brands and the effectiveness of advertising, the talent crisis, ad-blocking and avoidance, indeed many of the tribulations the industry faces might partially be a function of the fact that the public has come to believe that corporations are mostly scoundrels and thus exclusively concerned with their material gain, regardless of the impact to people or the planet. According to Edelman, trust in government and big business is at all time lows. The CEO of Edelman Europe, Ed Williams, suggested that “lying politicians, self interested businesses and CEOs that work for themselves and not their employees have contributed greatly towards the rising doubt that the public has towards UK institutions”.

A survey in HBR suggested that a majority of people now consistently believe harmful behaviours are used to increase profits, which is to say they are an inversion of the natural order, incentivised to behave in violation of society’s morals. So, perhaps, if your client or company really wants to be customer-centric, consider the path of the rogue.

Featured image: Don’t Pay UK