Speaking the language of internet culture is crucial for any brand — something we’re all, hopefully, well aware of in today’s late-stage social media era. But something you might not know is that in 2020, the global meme industry was valued at an inconceivable $2.3 billion dollars, and this figure is projected to almost triple by 2025. Or, that businesses who use memes in their marketing are 60% more likely to land sales than those who opt for traditional graphics. It’s a no-brainer — meme marketing makes a shedload of money.

That is, if it goes to plan. With a constantly rotating turntable of microaesthetics, image templates, and viral TikTok audios to choose from, it can be hard to wade through the noise and tap into trends that not only align with your brand’s personal voice and values, but are also able to stand the test of time. Leveraging your social media algorithms to spot memes as soon as they emerge isn’t going to cut it, either — this is merely the digital equivalent of knowing a few words in another language, but being unable to string together a conversation. Instead, it’s all about understanding the internet culture landscape as a whole — how we collectively use memes and in-jokes to communicate with each other over an extended period. And to fully grasp how to parse this ever-evolving digital language barrier, we first need to look at some examples of when brands have tried, and failed, at being chronically online.

When good intentions lead to… epic fails

The most colossal internet culture misunderstandings are usually tied to specific one-off occasions — be they films, TV series, sporting events, or competitions. While some movie marketing has been able to successfully harness online hype to its advantage (think last year’s Barbenheimer — a portmanteau that originally stemmed from Twitter and quickly became associated with these contrasting Santa Monica houses), more often studios are late to the party, unable to adequately assess how to use memes to gather and retain an audience. Perhaps the biggest example of this is Morbius — a 2022 Marvel film so poorly marketed, it immediately strayed into ‘so bad it’s good’ territory before it had even dropped.

This was lucrative and something Sony should have capitalised on, especially when the movie’s elusive plot (combined with their insistence on pushing it as the next big thing) quickly led to a slew of shitposters inventing amusing fake catchphrases for its characters. But by the time Sony became aware of the joke, sending Morbius back to theatres after a disappointing initial release, it was long past morbin’ time — causing the cringe vampire superhero film to bomb at the box office all over again.

Morbius highlights one of the most common issues we see when companies misunderstand internet culture — it makes them look tragically out of touch. The life cycle of all trends shortens by the day, especially with the 2020s emergence of microtrends, and memes are no exception. Weaving into this, too, is the tendency of many brands to jump on the bandwagon when a hyper-viral video or image emerges — all attempting, desperately, to shoehorn it into their marketing, instead of questioning why this particular meme might have gone viral, or how it aligns with their own personal social media strategy. This is typically called trendjacking and it doesn’t always work, especially if you’re not well-versed in internet culture, and when every other account online is also hopping onto the same trend. Speed means nothing here — nobody will notice whether you were the first to implement the latest auto-tuned cat in your marketing, if they can’t escape it on every single platform three days later.

Another mistake brands often make involves riffing on sensitive or controversial topics — compromising their moral integrity to play into a trending joke, and thus alienating a subsection of their audience. We’ve seen this in recent months with the influx of memes tailored around TV drama, Baby Reindeer. Characters and their alleged real-life counterparts have been turned into TikTok content by brands such as Aldi, leading consumers to label them ‘tone deaf’. It’s a story that keeps repeating itself over time — from Wendy’s accidentally posting Pepe the frog to Snapchat’s mockery of domestic violence. These oblivious misfires can cause monumental and sometimes irreversible damage to a brand’s image.

Considering the ethical implications before jumping on any meme or social media trend is always crucial, even if it seems innocuous. For example, the internet’s main characters du jour often include children and babies, who, along with their families, aren’t always equipped to handle the fame they’ve been given — brands should pay careful thought as to whether they want to add to this media onslaught.

How to read the room

So how can you read the room and get it right? Instead of pandering to shitposting trolls or relying on external, pre-cooked memes to elevate their products, the savviest brands are able to create and partake in their own lore and in-jokes alongside their audience, all the while retaining an air of self-awareness. One prime example is budget airline Ryanair, described by Dazed last year as ‘the internet’s most venomous troll.’ Instead of forcing the latest memes into their marketing strategy, Ryanair’s social team expertly use self-deprecating humour to poke fun at their own pitfalls, like ‘charging extra for breathing.’ Not only does this mirror the snarky, irreverent tone characteristic of much of Gen Z humour anyway (both in vibe and in visuals), but it sets a precedent for the brand’s tone of voice that allows them to then cherry-pick the most relevant trends, to further develop their persona.

Duolingo are masters at this too, and arguably take it a step further — characterising their owl mascot as some anxiously-attached, desperate sad boy (or girl!) you might see prowling around the apps and blowing up your phone with unwanted notifications. Here, not only can we see a brand poking fun at itself but also broader elements of dating culture and internet culture as a whole, that its target audience will be familiar with. By doing this, Duolingo demonstrate that they are, rather aptly, able to translate the language of Gen Z, while simultaneously developing their own instantly recognisable character.

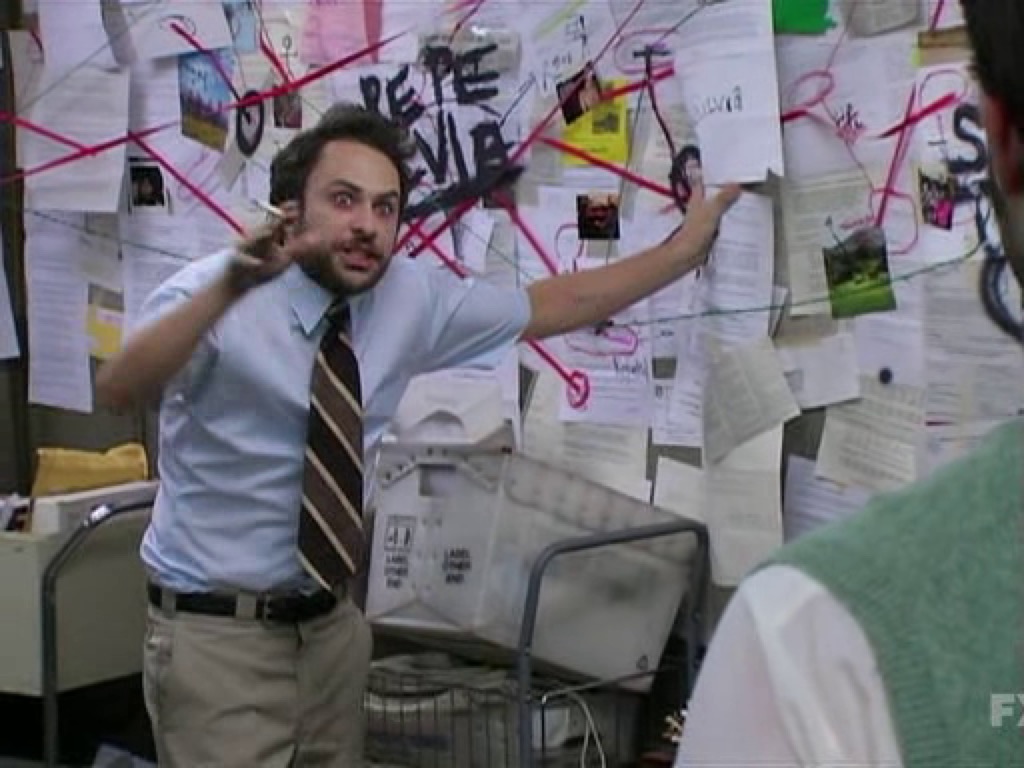

If you’re not clued up on every single trend, meme or internet slang term as it develops, don’t worry. Brands can still find success if they tap into timeless meme templates, untethered to any particular viral moment — as long as these aren’t overdone. Static images like It’s Always Sunny In Philadelphia’s Pepe Silvia scene, Drake Hotline Bling and the Distracted Boyfriend meme are so well-known that they might seem ones to avoid, but in reality, these images don’t carry an association to a specific time period or event — so they’re less likely to go out of fashion than say, a song or video.

Just think of the Corn Kid and ‘Chrissy Wake Up’ — both appeared much later, both quickly became tiresome and old.

Of course, the most important thing is to use any meme innovatively and in as novel a way as possible. And to stay as clued up as possible. By the time you’re reading this, the meme cycle will have inevitably moved on even further, so don’t get left behind!

Featured image: Morbius (2022) / Sony Pictures