When I think of Tokyo I recall the city’s irresistible energy. The neon-soaked scramble across Shibuya, the labyrinthine yokochos lined with sizzling izakayas — yet my memories are mosaiced by quiet moments too.

On the Chūō-Sōbu commute, morning sunlight dapples the dog-eared page of a shōnen manga. A man sips steaming ocha in a tucked-away kissaten and thumbs through the glossy pages of a magazine. In Akihabara, collectors scour shelves for trading cards and by nightfall, Shinjuku station is awash with salarymen, noses buried in evening editions of the Nikkei.

Japan is synonymous with technological innovation; yet in its effervescent centre, a deep connection to tradition endures. Understanding this duality is essential for foreign brands seeking a foothold in the Japanese market. Here, we’ll explore how the nation’s reverence for the tangible manifests in traditional media consumption. In our digital age, why do these physical formats persist? And with echoes of a similar resurgence in the West (think vinyl’s comeback), could these nostalgic trends offer a glimpse into the future of media worldwide?

Manga

Manga comprises over one third of Japan’s publishing market. In 2023, the medium was valued at over 693 billion yen (around £3.5 billion at current exchange rates). Whilst global giants like MangaRock and CrunchyRoll boast millions of users, Japan’s market thrives on a unique blend of publisher apps and brick-and-mortar stores.

Towering ‘new release’ walls and sprawling sections curated by diverse genres and demographics dominate major stores like Kinokuniya and Tsutaya. Convenience stores offer grab-and-go volumes, whilst the steady rise of unmanned bookstores and Tanagashi (rented shelves) demonstrates innovative adaptations from independent booksellers.

In Japan’s larger cities, specialty districts like Akihabara and Den Den Town aren’t just shopping destinations — they’re cultural hubs, havens for collectors to commune and seek rare editions, first prints and niche genres. These in-store experiences foster a unique sense of community; in 2023, Japan’s largest chain of used books, BOOKOFF, lifted its ban on tachiyomi, the practice of reading in-store before you buy. In Shimokitazawa, Tokyo’s buzzy secondhand district, Tsutaya offers a cafe, co-working space and the largest selection of manga around. Beyond bookstores, Japan’s ubiquitous manga cafes (mangakissas) offer enormous libraries of all-you-can-read manga, internet access and even showers, creating shared, comfortable spaces where patrons pay by the hour to discover new series, enjoy out-of-print titles and connect with fellow enthusiasts.

Newspapers

The Yomiuri Shimbun, Japan’s national daily newspaper, was founded in 1874 in the Meiji period (1868-1912) to answer the needs of a swiftly modernising society. Yomiuri (‘selling by reading’) refers to the vendors of the Tokugawa period (1603-1867), when news was printed on hand-graven blocks and sung aloud.

Today, Japan still boasts the world’s highest newspaper circulation rate. The Yomiuri Shimbun, in addition to the other four national dailies — Asahi Shimbun, Mainichi Shimbun, Sankei Shimbun, and Nikkei — reach over 30.84 million people daily; a decline from its peak in 1997, when newspaper readership was at 53.76 million copies.

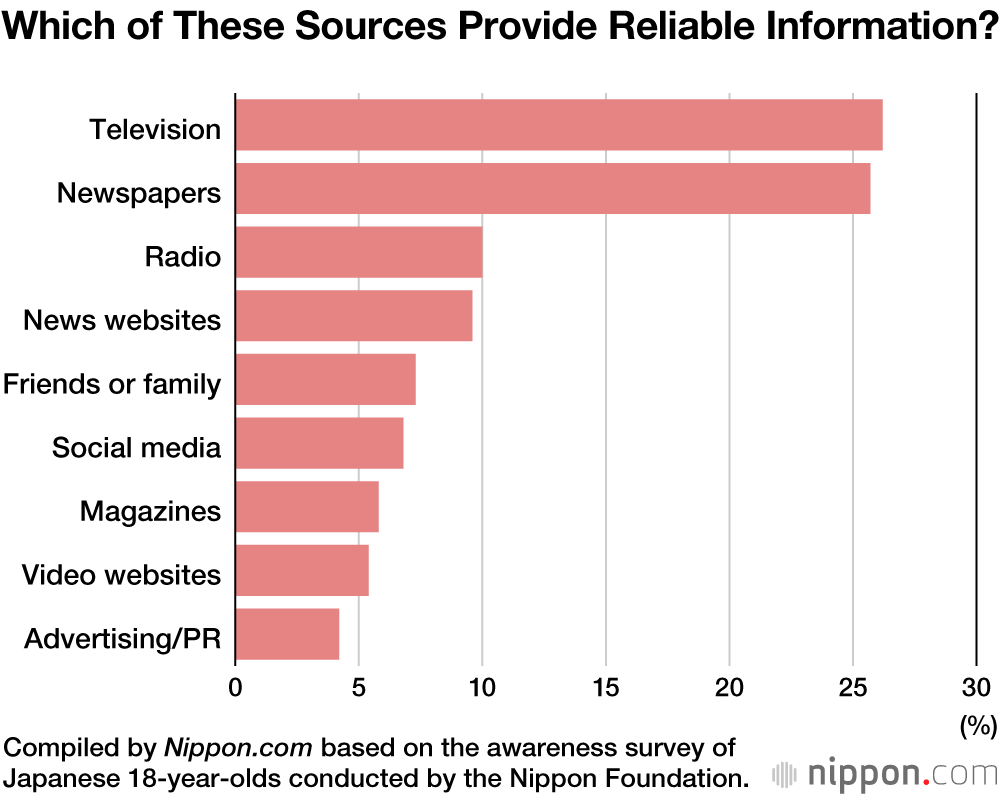

Whilst the implementation of paywalls reflects publications adapting to rapid digitisation, for many readers, tradition and trust remain key factors in media consumption. In a 2019 poll conducted by the Nippon Foundation, respondents ranked broadcast television and print newspapers twice as reliable as other sources of information. This established credibility of print has created long-standing loyalties, with many families subscribing to the same newspaper for generations. Japan’s super-ageing society, where a third of the population are over 65, are also more inclined to favour the tangibility of print over online sources. The Yomiuri Shimbun continues to restrict digital access to print and does not offer a digital-only subscription, highlighting a print-based readership that remains strong.

Magazines

The Meiji period also marked an era of rapid Westernisation in Japan, in which magazines emerged as powerful tools for mass communication. The rise of mass media and the subsequent demand for ad space spurred the creation of some of Japan’s first advertising agencies.

In her book, Magazines and the Making of Mass Culture in Japan, Amy Bliss Marshall explains how the Kingu and Ie no Hikari family magazines of pre-war Japan promoted ‘a conservative ideology of social conformity, family harmony and nationalism’ that came to define national identity en masse.

Contemporary magazines cater to more subjective tastes. Bright and bold Shūkanshi (weekly magazines) tabloids ‘chase scoops and scandal’, from celebrity gossip to political intrigue. In 2022, The Japan Times reported a fast-growing Zine culture focused on subcultures and niche interests, borne from a growing scepticism towards the homogenising effect of social media. When interviewed, Zine creator Keisuke Nagura remarked, ‘I wanted to leave people with something they can hold in their hands.’ These tactile experiences are captured best in the enduring tradition of Furoku, special freebies included with magazines.

Once a key disseminator of Kawaii subculture, these supplements range from stationery to handbags and even Pikachu-themed marriage certificates, catering to collectors of all demographics.

Vinyl

The Japanese vinyl market has exploded in recent years, with production skyrocketing sixfold to 3.9 billion yen (£19 million) from 2012 – 2021, according to the Recording Industry Association of Japan. In February, Tower Records announced it would be expanding its record collection by 50% at its iconic nine-floor Shibuya branch, to meet the demands of a growing appetite for analogue music.

Japanese vinyl pressings are highly sought-after worldwide, with Westerners willing to pay more for Japanese aesthetics.

Whilst nostalgia drives older consumers, the retro boom amongst Gen Z is a major force behind this renaissance. In the age of streaming, where music is ever-accessible, young listeners are drawn to the ‘time and effort’ involved with vinyl. ‘I don’t have a player, but I admire records,’ one 24-year-old told The Yomiuri Shimbun.

For others, vinyl is their first experience of physically owning music. ‘[The number of] young people who have begun listening to music on records since becoming familiar with city pop via social media such as TikTok is gradually increasing,’ Spotify’s Noriko Serizawa told Nikkei Asia. Purchasing used vinyl also aligns with Gen Z’s sentiments around sustainability, offering an eco-friendly alternative to constant digital downloads.

CDs and DVDs

Japan boasts the second largest music market in the world, a ranking they’ve maintained for over ten years. Whilst streaming reigns supreme worldwide, CDs remain the nation’s preferred format; the sales of which accounted for roughly 66% of the market in 2022, compared to digital distribution of 34%, according to the Recording Industry Association of Japan. The report also revealed that the sale of Blu-ray Discs increased by 12% to 20.34 million units and 15% to 40.8 billion yen, respectively.

The country’s vibrant fan engagement culture — known as Oshikatsu — plays heavily into these statistics. ‘Fans in Japan are particularly loyal to each artist, and many also have a collector’s mindset, making them partial to the physical product,’ Sony Music Entertainment Japan’s CEO, Shunsuke Muramatsu, explains.

These products often come with the added value of collectables, such as booklets, bonus features or meet-and-greet opportunities with J-pop stars. Fans will purchase multiple copies of these CDs for the chance to win these experiences and to show their support for their chosen Oshis. With a 90% domestic vs 10% international split on physical sales, a bias towards local genres also shapes the dominance of physical formats.

What we can learn

Collector culture is king

The popularity of Oshikatsu and Furoku reveals a willingness to spend beyond utility. Don’t just sell products; cultivate devotion. Partner with known idols, influencers and brands to offer limited edition merchandise, exclusive content and experiences tied to physical purchases.

Amplify the tangible

Japanese culture places enormous value on tactile experiences, yet the nation remains one of the world’s most technologically advanced. Bridge digital and physical worlds by offering captivating in-store experiences that seamlessly connect to online content via QR codes or interactive displays.

Tradition breeds respect

As Believe Japan’s General Manager, Erika Ogawa, writes: ‘Once the Japanese have established a method, they master and perfect it, and demonstrate a strong commitment to keep building on what their predecessors have built.’ Earn trust by partnering with established media outlets or find ways to honour Japanese heritage in your offerings.

Huge thanks to Madoka Suganuma, whose insights and provided resources helped shape my understanding of Japanese media and the development of this article.

Featured image: Martijn Baudoin / Unsplash