We can all sense there’s a problem with subscription services…

Somewhere deep amidst the bits and bytes they are messing with our concept of ownership. It used to be so simple — either you rented or you bought. Now with the rise of subscription services, there are shades of grey in between. Maybe you get the benefits if you are a member, while others offer joining deals to get you in. Even once you’re in, you need to navigate between the items you’ve activated and must use and then remember the items that expire if you don’t activate them.

But then, in terms of the customer experience, there’s the worst of all offences, and my pet hate, ‘purchases’ that are really rentals in disguise. It’s a seller tactic from the pit of darkness itself.

This complexification can nowhere be seen more prominently than in the world of video streaming

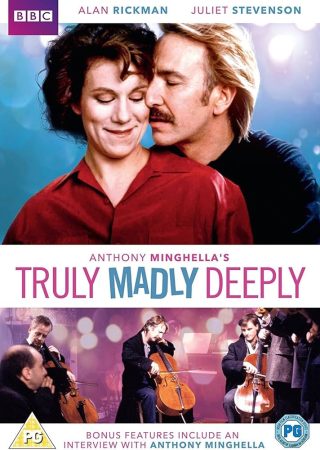

Let’s consider Amazon Prime as a case in point. I recently listened to a lovely Radio 4 show where the fabulous Juliet Stephenson explained some of the backstory behind one of her greatest films. I remembered really liking the film itself, Truly, Madly, Deeply (1990), and thought it was time to rewatch it.

Sure enough, I found Amazon Prime streams it and offers me to ‘buy it‘ for £12.99 in High Definition (no less) anytime I like. I can also ‘rent it’ for £4.99. Yet here begins my dilemma — do I buy or rent? Will I, and my immediate family, want to watch the three times the price point requires? It’s difficult to say! It was a good film, but was it that good? I can imagine my wife, who hasn’t seen it yet, wanting to share it with her sister, for sure, but then only if she enjoys it herself.

Even having the option of renting or buying still feels pretty new to me. I grew up in a time when you could either go to the cinema, wait a few months to rent or wait a few years till it premiered on linear TV. In those days of VHS tapes (and then DVDs) buying a film like Truly, Madly, Deeply meant you owned it, in that medium, and you could do pretty much what you liked with it. Lend it out, give it away, keep in the attic, dump at a charity shop or watch it over and over again — the power was yours.

Now, when I buy on Amazon Prime, what am l really getting?

Not much more than ‘the right to watch the film when l am logged in.’ In this world, my sister-in-law doesn’t get a look in and I can never sell it on. If I can’t give it away or sell it then clearly I’ve not bought it in the first place. Most concerning, however, is when I ask the existential question: what happens if Amazon decides to sunset the entire Prime video service? If that happens, I will lose access entirely to this wonderful movie and it will turn out that I never in fact ‘owned’ anything after all.

So in what sense am I actually buying? Or is ‘buying’ a film on Amazon really just a long-term rental, one where the expiration term is decided by the platform itself? I never own the movie in the medium. Or am I really just on a long-term lease? One that expires at the arbitrary decision of the big tech powers that be? And arbitrary platform sunsets happen in the world of streaming.

When Twitter pulled the plug on its short-form video service Vine in 2016 — Viners with millions of followers lost their fanbase overnight — they didn’t own quite what they thought they did. Earlier this year Google sunset its ‘Stadia’ service for video gaming streaming. When this happens, it’s us humble consumers who may be the ones to lose everything we’ve bought and created on the platform — Stadia chose to reimburse purchases rather than risk a PR firestorm, yet gamers still lost all the hours they’d sunk into building their video game profiles.

So what’s to be done?

Well here’s a trick taken from the world of business software, another entirely digital product. When I was selling software on a monthly rental to a big blue chip firm, their lawyers insisted I provide a copy of the actual source code for cold storage in ‘escrow’ — what this meant was that in the event that our company folded, they would then be able to access the software and spin it up for themselves. They didn’t mind renting, but they didn’t want the risk of losing it all.

I think consumers buying movies and box sets on Amazon Prime should have the same protection — the knowledge that if Amazon closes they can download the MP4 file version of films they’ve bought from escrow. But that protection isn’t in place today. If you check Amazon’s Prime Video contract terms you won’t be surprised to hear that they can shut the service and you’ll lose access to the content. The small print reads even worse — if Amazon loses access to the original film rights for example to Truly Madly Deeply — you’ll lose access too, even if you’ve ‘purchased it!’ Shades of grey indeed.

Featured image: Denny Muller / Unsplash