Us humans can be pretty good at ignoring the issues we’d rather not face.

There’s evidence that we’re adept at looking away and hoping the problem will disappear. It’s a bias called the ostrich effect.

Buy or sell?

One study into the ostrich effect comes from the world of finance. In 2009, George Loewenstein and Duane Seppi from Carnegie Mellon University studied the behaviour of investors.

The researchers analysed the habits of US stock and Swedish stock investors by analysing data from the fund manager Vanguard. They were interested to see how often investors monitored their funds at different stages of market activity.

They found that when the American stock market was rising, US investors checked their portfolio 5-6% more times per day for each 1% upwards swing. Swedish investors showed a similar though less pronounced trend, checking progress 1% more when the Swedish stock market rose by the same amount.

Both groups gave relatively less attention to their accounts when the markets were on a flat or downward trend.

This selective attention means investors were choosing what information they wanted to learn. They picked good news over bad, potentially to their own detriment, since arguably, it’s more important to keep tabs on your portfolio during a downturn.

Ignore the ostrich

The fact that we tend to tune out of bad news has important implications for communications — particularly when bad news is what you’re bearing.

An example might be a health campaign such as anti-smoking. These campaigns have often taken a fear-inducing approach to try to persuade people to quit.

But given our tendency to turn away from such messaging, how effective will they be? Psychology would suggest that other approaches may be better at breaking bad habits.

A great success story, which beautifully harnesses a handful of biases, is the Stoptober campaign. Rather than focusing on the harms of smoking, it hangs on a few key psychological principles to encourage quitting attempts.

First, it makes your attempt appear easier, by giving it a month-long time window. This seems less of a daunting prospect than never smoking again. Research into habits shows that starting with small steps gives a good base to build on.

Second, it’s social. It turns quitting into a collective enterprise, encouraging smokers to share their progress and gather support from others. Even the act of publicly stating your intention to quit can be enough to make it happen.

And third — it’s time scarce. New habits are far more likely to develop when a person sets a time-specific plan and commits to it. Stoptober sets up the month of October to give it go — so when October rolls around, you’re ready for action.

And it seems to work. The first Stoptober back in 2012 increased quit attempts by 50% compared with the other months of the same year. In fact, one study estimated that Stoptober that year could be credited as having provoked additional 350,000 quit attempts. That’s a lot of cigarettes left unsmoked.

So my advice to you when bad news is on the agenda: Shift the focus somewhere else, entirely.

Ostrich behaviour backfires

Of course, the head-in-the-sand behaviour is not actually an effective survival technique. Clearly, if you can’t see your predator coming, you’ll soon be tiger food. And actually, it’s a myth that ostriches are trying to avoid the baddies when they do it — they are in fact turning their eggs, which they bury in the ground.

So ostriches don’t do it, and neither should we. My advice is, stay alert to health issues, financial crises — and tigers.

Only then can you decide whether to stand your ground and fight the beast — and how exactly you’re going to land your best punches.

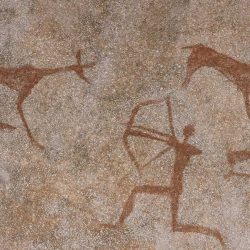

Featured image: The Everett Collection / Canva