As marketers, we tend to focus on what our competitors are doing. But that’s why categories end up feeling samey. For cars: a shiny motor handling tight bends amid beautiful scenery. Or perfume: a buff celebrity staring into the distance on a beach, with frequent jump cuts. Or soft drinks: lots of splashing water and close ups of fists grasping cans. You get the picture. But I’d suggest that we need to look further afield if we want to get fresh ideas. And, in line with this month’s topic, one such area is politics. At its heart, political marketing has the same goal as any brand — to create a change in behaviour through persuasion tactics. And often it’s very effective.

Do we like questions?

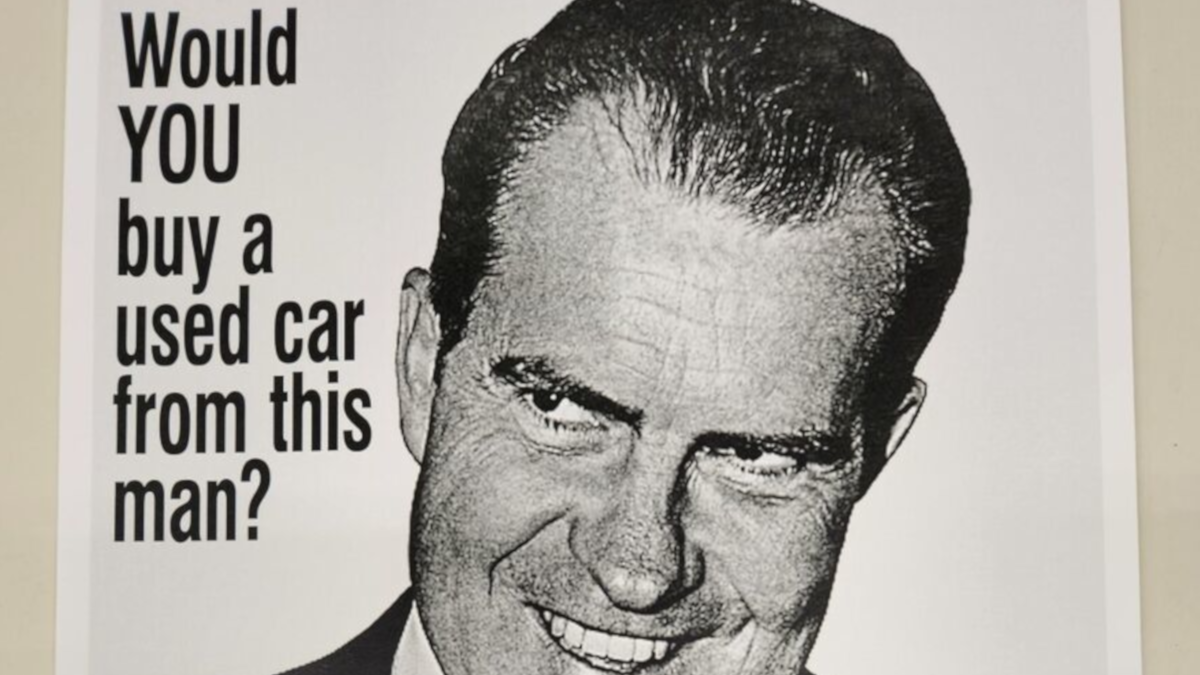

I want to focus on a famous campaign from 1960s America: the anti-Nixon campaign that caused such a stir. Nixon was the Republican candidate, up for nomination as President in 1960. He was already well known, having sat as Vice President since 1953. During that time, he’d been given the nickname ‘Tricky Dicky’ by the Democrats for the campaign tactics that got him there.

The first recorded reference to the used car salesman question is in an account of the Democratic National Convention. And after that, the Democrats used it to great effect.

Why does it work? I think the answer lies in behavioural science. The headline — Would you buy a used car from this man? — is a question. More than that, it’s a rhetorical question: the answer they’re looking for is a resounding, ‘No!’ This is implicit, because the image portrays Nixon with the kind of smarmy fake smile and finger-point you’d expect from a slightly dodgy salesman — not someone who inspires trust.

There’s good evidence that rhetorical questions are especially persuasive compared to simple statements. One study comes from Rohini Ahluwalia from the University of Kansas in 2004.

She asked 135 participants to evaluate various newspaper articles and adverts. The content included either questions (for example, ‘Did you know that wearing Avanti shoes can reduce your risk of arthritis?’) or statements of identical information (such as, ‘Avanti shoes can reduce the risk of arthritis.’). After reading the pieces, participants’ attitude towards the brand was assessed on a nine point scale. And results showed that attitude scored 11% higher when the ad featured a question compared to a statement.

The question format had more successfully persuaded readers about the merits of the brand.

What’s going on? Well, rhetorical questions increase the effectiveness of text, first because they are distinctive, which attracts attention. Essential for any ad. And second, they encourage the reader to pause and reflect, making them an active participant in the messaging.

So employing a rhetorical question on the anti-Nixon poster was likely to have worked better than a simple statement because it engaged the audience and forced them to question his trustworthiness.

Bring it to mind

And there’s something else going on with rhetorical questions. Because forcing the reader to come up with an answer is using another technique, which has been shown to boost memory. It’s called the generation effect, and it describes how our brains naturally come up with answers to fill gaps.

The original finding dates back to 1978, and a study from Norman Slamecka and Peter Graf. They found that participants who were required to generate words rather than simploy read them recalled 15% more words. It’s a finding that has been replicated since. In 2020, I ran a new piece of research with Mike Treharne at Leo Burnett for my book, The Illusion of Choice. We either asked 415 respondents to either read the name of a brand in five categories (e.g. banking: HSBC), or generate the same brand name by filling in the letter blanks (e.g. banking: H _B C). At the end of the survey, we asked respondents to look at a list of three brand names per category, and identify the ones they had read or generated as the first task. The average recall rate among ‘generated’ brands was 93% versus 81% for those that were simply read. This means there was a 15% increase in memorability for words that participants were forced to generate. Or, looking at it from the opposite perspective — just 7% failed to remember the brand when they’d generated the word. But 19% couldn’t remember when they’d merely read the brand name.

That’s a 2.5-fold difference. The generation effect is an idea that brands can harness effectively, and features in some of the smartest campaigns.

From politics to commerce

Rhetorical questions and the generation effect can be applied commercially too. A great example is the Saatchi and Saatchi campaign which launched The Independent newspaper in 1986. The ads featured the line ‘The Independent. It is. Are you?’ to highlight the independence of thought that featured in the paper — and by extension, its readers.

So, by encouraging the reader to generate an answer, a rhetorical question is thus likely to be noticed — and also remembered. And this, I think, shows us that while we may not want to ape every tactic from political campaigning, we can see some pretty innovative ideas in use. And some of these can certainly be applied to other campaigns to equal effect.

Do you think you might take another look at questions?

Featured image: Anti-Nixon poster, 1960