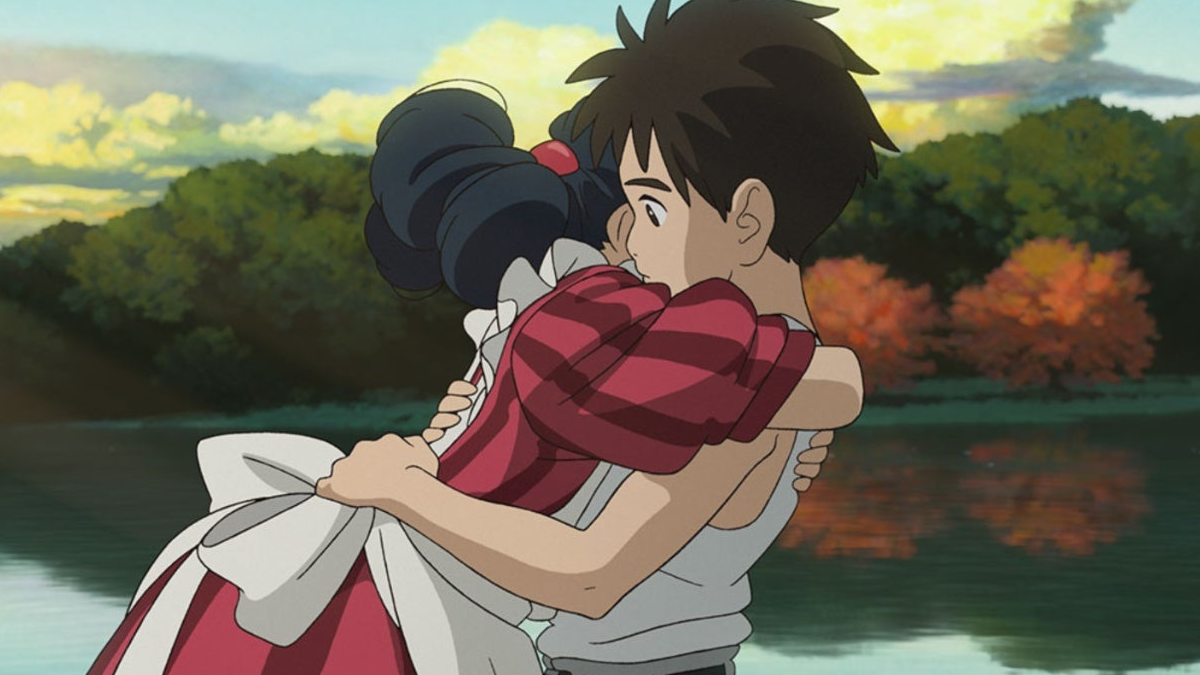

When Japanese anime film The Boy And The Heron completed the filmmakers Triple Crown last month (in March), by picking up an Oscar to add to its BAFTA and Golden Globe for Best Animated Film, few outside the industry will have noted the significance of the moment.

As with anything that precipitates a shift in a cultural movement, the repercussions will not be obvious for some time, but critics will be able to point at the early months of 2024 as the moment the wider world woke up fully to anime. An art form for more than a century, it began to flourish in the 1940s and ’50s, and hit its stride in the 1980s (thanks, in no small part, to the work of The Boy and the Heron’s creator, writer and director, Hayao Miyazaki) and went truly international when Miyazaki’s Spirited Away won the Best Animated Film Oscar in 2003. (Side note: the Golden Globes saw not one but two anime films among the Best Animation nominations this year, with Makoto Shinkai’s Suzume up in lights, too.)

While growth has been slow, the sector is projected to be worth $37bn by 2025, with the likes of Netflix and Disney now investing in multi-million-dollar adaptations of key anime IPs. It is gathering at such a pace that, last summer, leading anime streaming service Crunchyroll — which has 13m subscribers globally — appointed my team to manage publicity for all UK title releases, signalling the company’s first major investment in reaching UK audiences. Oh, and readers in the UK who think the phenomenon has passed them by should be reminded that Pokemon is one small part of the anime world, which has firmly landed in the mainstream. Purists will scoff, but it is these seemingly minor cultural players that are paving the way for a limitless supply of similar content to follow.

(Girl) power to the people

For a recent reference point of the power of entertainment to influence culture, we need look no further than the five women who came to define British pop music in the 1990s: The Spice Girls. They arrived with their message of Girl Power at a time when feminism was a dirty word, and the music scene was dominated by lad culture and grubby boys playing guitars. This manufactured quintet’s (relative) individualism, defiance and message of empowerment quickly captured the imagination of not just girls and young women, but anyone seeking to find their way in an era where conforming was still the norm.

More recently, the Barbie movie captured the imagination of everyone — not just girls and women — by using its platform to bolster important conversations. Too much attention has been given to its lack of awards success; not only was it 2023’s highest grossing film, but the fact it grabbed our attention, made its point and got the world talking about the hypocrisy of gender issues, was enough. Meanwhile the Barbenheimer phenomenon was adopted by mainstream culture purely based on the idea of two completely different films being released on the same day. Memes, double features, coverage and merchandise all helped blow both films into pop culture status, rather than just a run-of-the-mill film release.

Korean culture goes global

Perhaps the most powerful example of entertainment driving a wider global movement — cultural, social and political — lies in the growing dominance of Korean culture. Spawned out of 1997’s Asian financial crisis, Korea turned to its strong but very localised entertainment assets to rebuild its economy. K-pop stars soon started to be noticed by Western audiences with the first K-pop concert in Europe, in 2011, selling out all 14,000 tickets.

Meanwhile, who can forget Psy’s Gangnam Style, which set new chart records the world over in 2012? Fast forward to 2021 and BTS (who have become one of the biggest-selling bands of recent years) were addressing the UN General Assembly on the issue of climate change. The wholesome lifestyles and values advocated by K-pop bands, together with their slightly androgynous and eternally youthful, avatar-like style, have struck a chord with Gen Z audiences and come to define a subculture of sorts.

The Korean attitude has become a global enterprise, flourishing across the world not only in music but in all strands of entertainment — from TV (Squid Games remains Netflix’s most successful show) and film (2003’s Old Boy is a cult classic) to video games (South Korea is a pro-gaming powerhouse) — as well as food, fashion and even interior design.

An accusation that has long been levelled at entertainment is that it reflects the attitudes, tastes and styles of the day, but if we look at the matter retrospectively we can see that entertainment is actually a precursor to cultural shifts. Its ability to tap into existing interests, harness passions and capture the mood of a generation is what makes it such a powerful force, while our inability to predict where it will go next is what keeps everything so very interesting.

Featured image: The Boy And The Heron (2023) / Studio Ghibli