In our era of tumultuous change, a challenge you might face is encouraging consumers to accept radical innovation.

Perhaps the best way of understanding how to do this is to learn from other eras characterised by similar levels of instability. Take the mid-nineteenth century. In 1848 Marx captured the bewildering pace at which society was evolving: “All fixed, fast-frozen relations, with their train of ancient and venerable prejudices and opinions, are swept away, all new-formed ones become antiquated before they can ossify. All that is solid melts into air, all that is holy is profaned.”

If anything, the rate of change intensified as the nineteenth century progressed. Radical ideas like evolution shook up how people viewed their place in the cosmos. A constant stream of inventions disrupted society. From the washing machine to the Gatling gun, the combustion engine to the telephone, inventions came thick and fast over the next thirty years.

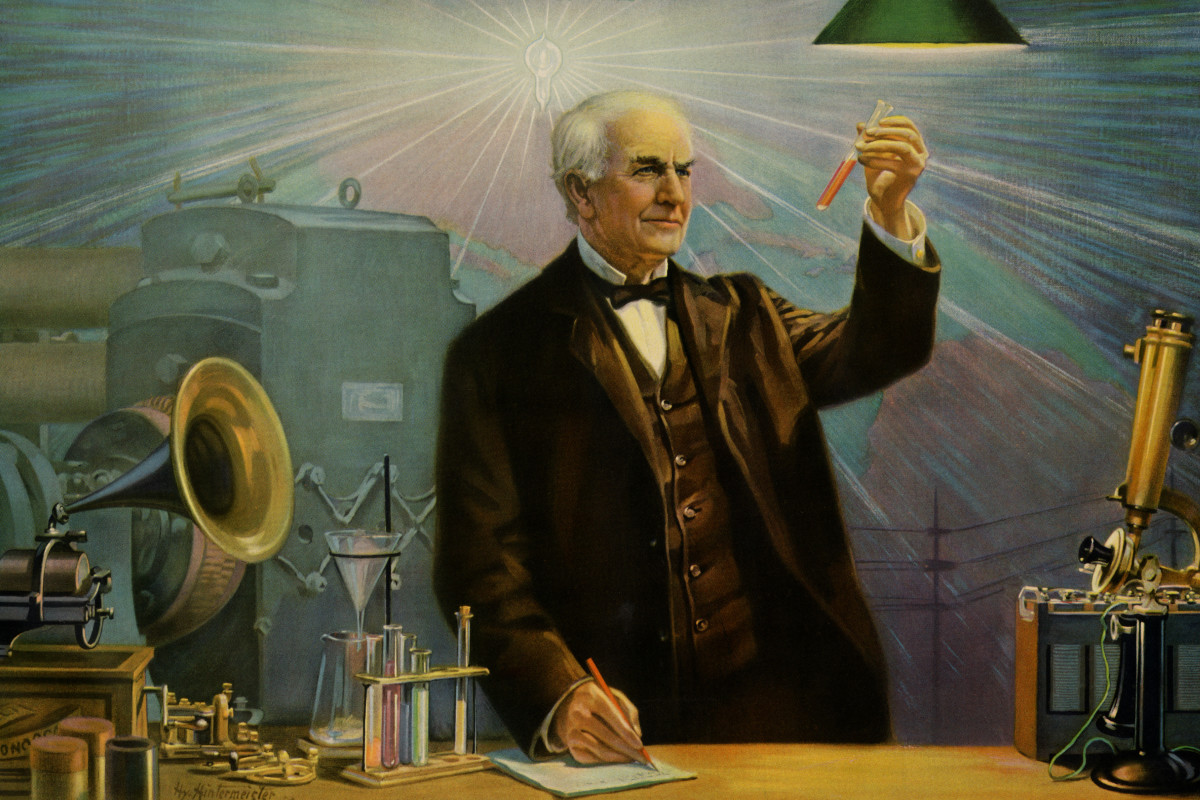

But of all these new technologies, it’s Edison’s lightbulb that is most instructive. For Edison wasn’t just an innovative inventor; he had a deep understanding of the public. He recognised that disruptive ideas both excited and scared people and that the element of fear hampered adoption.

So, according to a 2001 paper by Andrew Hargadon of the University of California, the inventor made a concerted effort to portray his innovation as more familiar by aping the previous gas technology.

In his notebooks he said he wanted to “effect exact imitation of all done by gas, so as to replace lighting by gas with lighting by electricity… not to make a large light or a blinding light, but a small light having the mildness of gas.”

So, Edison set the power of the electric bulb at 13W – almost the same as the gas lamp — even though it was capable of far higher brightness. He copied the gas lamp tradition of using light shades, even though these were superfluous — their original purpose was to stop the gas flame guttering in the wind. He even insisted that electricity cables were placed underground — like gas — rather than using pylons, like the telegraph.

At each step, he mimicked the preceding technology to assuage the public’s fears.

This approach of adopting the design features of a previous technology is known as skeuomorphism

It’s a technique that stretches back far beyond Edison.

H. Colley Marsh, who coined the term, noted that archaeological finds showed ancient pottery had patterns resembling basket weaving and that bronze axes mimicked the design features of the flint technology that preceded them.

Skeuomorphism isn’t just a historical quirk. It has played an important role in acclimatising sceptical audiences to modern technology.

When Steve Jobs launched the iPhone, he was conscious that it was disruptive, so he harnessed skeuomorphism to make it less daunting. For example, the icon for the podcast app looked like a reel-to-reel tape player, the contacts app looked like a spiral notebook, the notes typeface mimicked handwriting — even the camera made a clicking sound, like one of its mechanical forebears.

The efficacy of this tactic isn’t just anecdotal

In 2014, Karim Lakhani, a professor at Harvard, investigated what type of research proposals were most likely to win funding. He sourced a list of 150 proposals and ranked them according to their degree of novelty. He then asked 142 world-class researchers from a US medical school to evaluate them.

Lakhani found that the researchers ranked the most novel submissions worst and the highly familiar ones only fared slightly better. In contrast, it was those that had “optimal newness” that scored most highly.

The idea of optimal newness is key. If your product is genuinely disruptive then skeuomorphism is a powerful tactic, however, if your product is already familiar then it’s probably inappropriate.

Again, the example of Apple is instructive. By the time iOS 7 was launched in 2013, the technology was no longer so radical, and Jony Ive toned down the use of skeuomorphs, preferring a more minimalist approach.

The task for you as a marketer is to honestly reflect on how ground-breaking your product really is. If you can answer that accurately then the right design tactic becomes clear.

In the words of Atlantic columnist, Derek Thompson, “to sell something surprising, make it familiar; and to sell something familiar, make it surprising.”

Astroten’s next workshop on applying behavioural science to marketing will be in June. Details here.

Featured image: Thomas Edison / history.com