What springs to mind when you think of rogues in marketing? For me, it’s the escapades of Victorian entrepreneurs. People with a flamboyant approach to marketing, who were prepared to sail close to the wind when it came to convention.

One of the most successful was Thomas Lipton. He was born into poverty in 1848, in a slum in the Gorbals, Glasgow. He started out as a grocer. And by the time he died eighty years later, he had founded and grown Lipton Tea, the biggest tea brand in the world. In today’s money, he was a billionaire.

His success as a retailer was based on an astute sense of what captured the public’s imagination. This often involved marketing ideas with a sense of spectacle.

A sense of spectacle

Lipton’s first major stunt ran just before Christmas 1881. To much fanfare, he imported from America what he claimed was the world’s largest cheese. That record may or may not have been true: sticking puritanically to the facts wasn’t in his nature. However, by any scope, it was a massive slab of cheese: 14 feet in circumference and two feet thick. It weighed 3,472 pounds and according to Lipton, had required 800 cows to be milked for six days.

When the cheese landed at Glasgow docks, Lipton christened it Jumbo, and put it on display. To enhance the sense of value and scarcity, he hired a bevy of police officers to stand guard.

Having drummed up plenty of interest, he rolled the cheese to his store. Next, he thrust handfuls of gold sovereigns deep inside the cheese. Despite the fact that lotteries were illegal, he then proceeded to sell small slices to the public.

Within two hours of opening, the last piece was sold.

Lipton’s stunt was so successful, it became his Christmas tradition. Each year he would conjure new ways of capturing the public’s attention. On one occasion, the cheese was dragged to his store by two elephants he had hired from a travelling circus.

Any fool can make soap

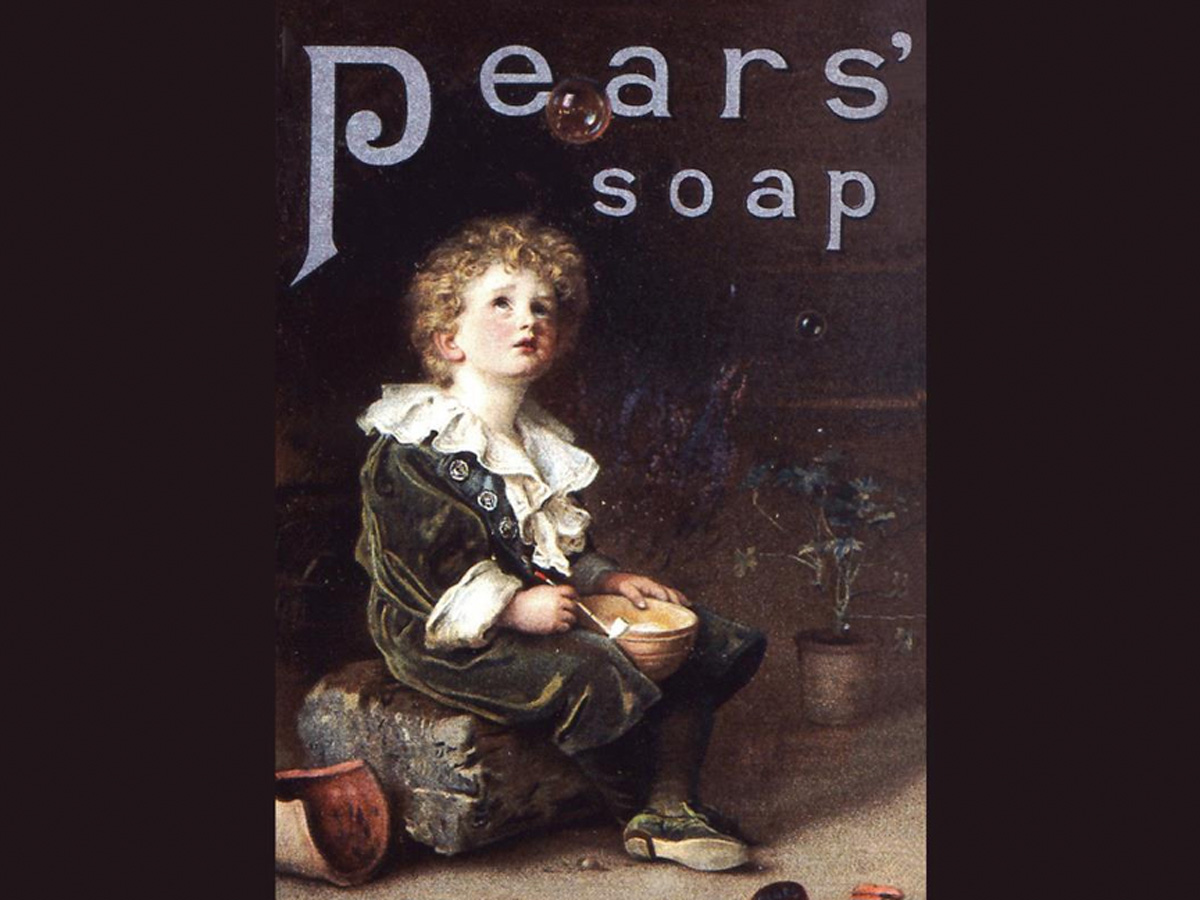

Lipton’s flair for marketing was perhaps only superseded by Thomas J. Barratt, who grew Pears’ soap into one of the most famous brands of the 19th century. And he attributed the stratospheric growth to the company’s marketing. In his own words, ‘Any fool can make soap. It takes a clever man to sell it’.

Barratt’s best-known marketing stunt was spending £2,200 (about £200,000 today) on the rights to a famous contemporary painting by Sir John Everett Millais, called Bubbles. Much to the artist’s horror, he doctored the image by adding a bar of soap. He then turned it into an ad that he ran at excruciating frequency in the press.

However, it’s another of his gimmicks I want to focus on. In the 1860s, he wanted to keep the Pears’ brand front of mind without spending on media. So, he exploited a loophole in the law. At the time, tampering with British coinage was a severe crime. But French centimes were still legal tender in Britain. So he imported 250,000 centimes and engraved them with “Pears’ soap”.

You can see an example below.

Barratt paid his staff with the centimes and as they then spent their wages, his message spread through society. All without spending a penny on paid media.

Eventually, the government changed the law so that French coinage was no longer legal tender and no-one else could pull the same stunt.

What can we learn from these stunts?

First, that the past can be a source of inspiration for today’s campaigns. Steve Jobs said that creativity was just “connecting the dots”. He argued that if we’re going to come up with fresh, distinctive ideas, then we need to expose ourselves to as wide a range of experiences – or “dots” – as possible.

So, we should seek inspiration in areas where others aren’t looking. All of your competitors will know what was successful at Cannes this year, few will be looking back at the Victorians for bright ideas.

Second, the potted histories of Lipton and Barratt show that moral rectitude and flair for attention are different things. There’s no reason to think they must go together. But I fear that sometimes our industry treats them as inseparable. Think about marketing conferences – we often hear from charities and social projects. But how often do you hear from speakers drawing lessons from those at the other end of the moral spectrum?

If that feels like hearsay, think back to a few years ago when Campaign ran an interview with Nigel Farage. It was met with apoplexy. In an unprecedented step, the editor wrote a contrite follow-up column addressing the barrage of complaints.

But surely, we can learn from people we disagree with – perhaps even dislike. Dismissing everything they do as lies and manipulation is simplistic.

Our role as professional communicators is to extricate the two things – the person and the tactics. Some of their tactics might be immoral in and of themselves and those should be ignored. But other tactics may be morally neutral, and these we could apply in other situations.

After all, as one of Lipton’s contemporaries, William Booth said, “Why should the devil have all the best tunes?”.

Astroten’s next workshop on applying behavioural science to marketing will be in September. Details here.