A year on from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and with no end to the conflict in sight, it’s hard to find many signs of hope in the country. But two independent magazines, one Ukrainian and one Russian, and both published last year, find fresh perspectives and manage to raise themselves above the utter hopelessness of the conflict.

Publication 1: Solomiya

A magazine made by young creative people from Kyiv and Berlin, Solomiya is themed ‘war but art’, and it’s a potent mix: it includes a photo story, shot around Kyiv in April and May last year, which mixes street style with civilian defences, its models pictured alongside sandbags, concrete barricades and anti-tank hedgehogs. These are people living in a country at war, but who also thought hard about what to put on that morning.

It would be easy for this fashion aesthetic to feel glib or tasteless, but Solomiya also has some of the simplest and most authentic commentary I’ve read about the experience of being at war. The long story, Surviving Bucha, details day by day the horrors endured by students Christina and Artem, beginning with the outbreak of war on the 24th of February and the nightmare that turned their quiet, middle-class town into a symbol for the worst atrocities of war.

Christina’s initial response to the Russian invasion feels particularly understandable — convinced that they should stay away from nearby Kyiv because it was more likely to be the target of Russia’s forces, she persuaded her mum that they should stay at home. “I didn’t take the idea of war seriously. I thought it would be like Covid: we get a lot of food, stay home, and just wait until our armed forces do their job, and then it’s over.” Their accounts of life over those days is almost unbearably tense, filled with fear of the enemy, but also frustration at the selfishness of neighbours, confusion spread by rumours and misinformation, and occasional moments of hope and humanity.

By contrast, a series of profiles is dotted through the magazine, detailing the work done by young volunteers in setting up organisations providing aid, relief and military supplies. The profiles are rotated 90 degrees and printed on a yellow background, helping them to feel brighter, lighter and more optimistic. Hugely impressive as a first issue, Solomiya has immediately established itself as a voice on the war in Ukraine, and a second issue is in the works. I hope that as long as the conflict continues, Solomiya will keep on publishing its unique perspective.

Publication 2: Bl8d

By contrast, Bl8d (which can be read as ‘blood’) offers a desperate Russian voice against Vladimir Putin and his military commanders: “Reader, the magazine you are holding in your hands is our common anti-military manifest, our voice against the war. It is our anger and rage towards those who started this war, and those who still support it. It is our tears of helplessness and despair from the realization of Irreversibility of what has happened. It is our fears and an attempt to look at ourselves in the mirror to understand how this could have happened to all of us? It is a hope for the Light which one day will incinerate the Untruth and give us hope for Forgiveness.”

The opening letter explains that this is, “a bastard… a magazine that should never have been released.” The team had originally intended to make a 200-page trendbook, using it to investigate the essence of the “Russian code”, which I think means the underlying characteristics and influences of ‘Russianness’. The trendbook was ready to be printed, but when Russia invaded Ukraine they destroyed what they had done, and set to work instead on the project that became Bl8d; a magazine that records their disillusionment, shame and anger, and also tries to understand how this terrible version of Russia has come to pass.

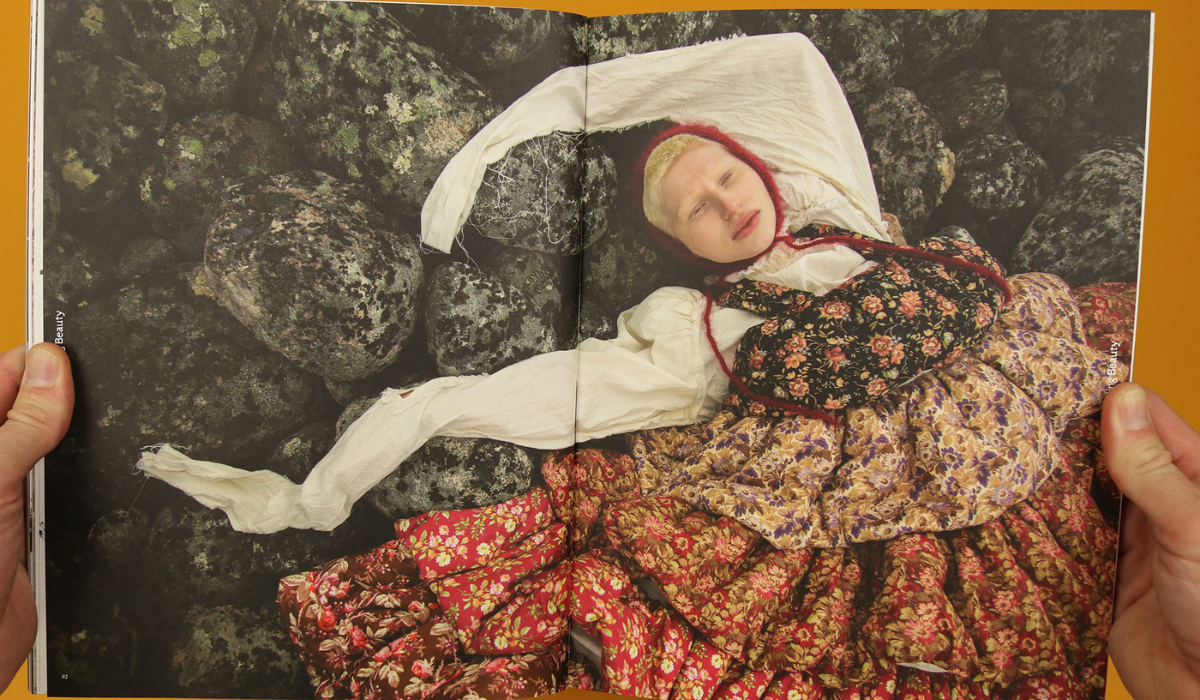

The magazine is based around two interviews; one with art historian Tata Gutmacher, and one with museum researcher Denis Danilov. Their words are set alongside photography and artwork by several Russian contributors, some named and some anonymous, some living overseas and some still based in Russia.

There are people who will think it’s inappropriate for any Russian perspective to be promoted at the moment, and probably even more who will feel offended by an attempt to aestheticise it in the way Bl8d does, with its abstract graphic design and its fashion and fine art imagery. But this is a beautifully humane publication and Tata in particular provides a fresh understanding of how at least some Russians are feeling in this moment.

“Everyone has the internet,” she says, “the majority has everything working even without VPN. But why don’t people see? Now, of all the times? Go online, use Telegram… It’s not about access to information. Like in times of the Third Reich Germans knew enough not to want to learn more. The same is now. People don’t want to find out more.”

Asked about the fate of Russian culture, she replies, “Right now we need to stop thinking about ourselves. Right now we don’t need to be saving the ‘Russian idea’, right now we need to be saving the lives of Ukrainian girls, boys and elderly women. And those brainless Russian boys who went to war. And brainless Russian mothers who sent their children to this war. Right now we need to save people, not culture.”

As much as she clearly wants to see the end of the bloodshed, she predicts more to come, with a civil war that will spell the end of Russia as we understand it today. This beautiful and bleak magazine doesn’t offer much in the way of hope for the immediate future. Instead, it uses self-reflection as a way to build bridges and offer the world an explanation for how we ended up where we are today, and to hope for a more peaceful future.

Featured Image: pages of Bl8d magazine