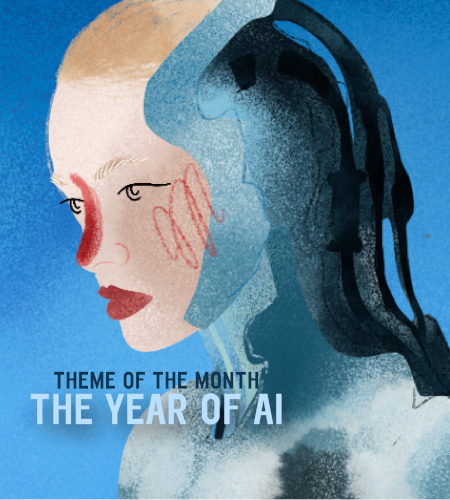

Like many, technology has had a huge impact in shaping my experience of music through the years.

In 1983, when Herbie Hancock rocked a keytar and GrandMixer D.S.T. scratched the turntable, my own personal music journey was off to a flyer. It was music from another planet and wanted to hitch a ride on the nearest spaceship.

Years later, when Apple announced in 1998 that with a single small white box you could have “1000 songs in your pocket” and look fly AF with white earphones, I was in.

Sign me up. Take my money. Incredible.

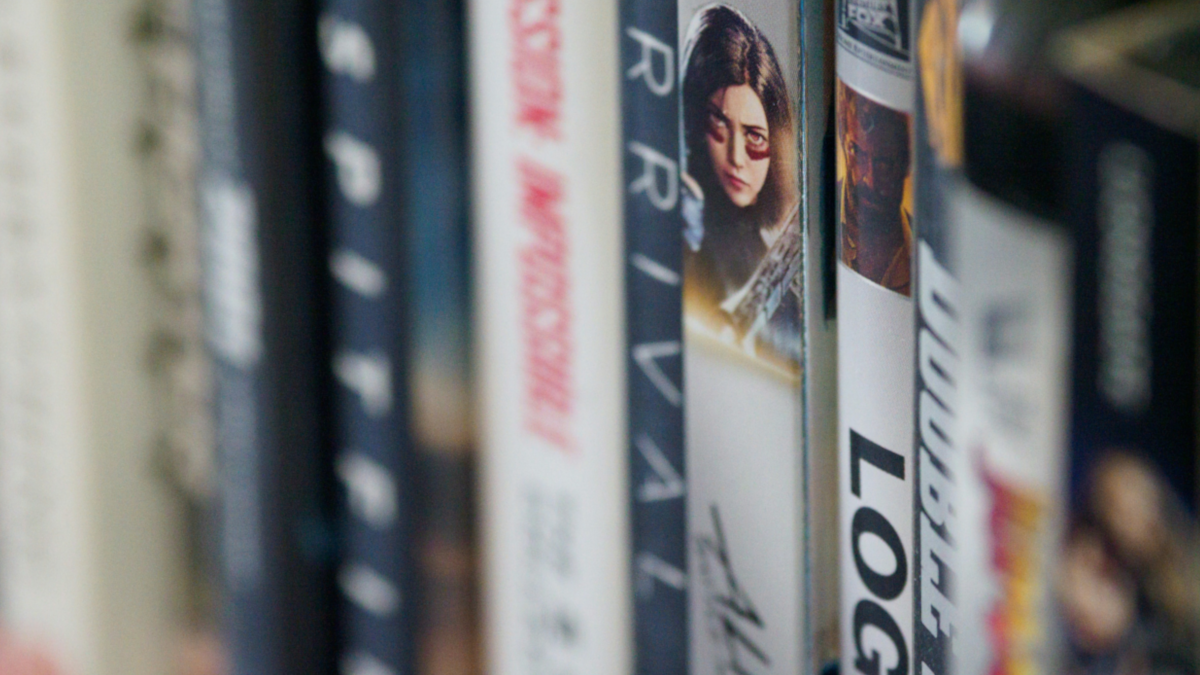

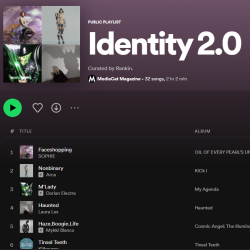

And as an adult who would spend a larger proportion of his income on CDs than anyone would deem sensible, when Spotify offered me unlimited access to pretty much all the songs in the world without having to lug them from flat-move to flat-move, I thought I’d died and gone to music heaven.

All the songs? All the time? What a moment to be alive!

From gramophones to CDs, instruments to synths, ownership to streaming, technology has fundamentally changed the way that we create, consume and share the music that we love. And depending on which way you look at it, this has either been the end to music as we know it, or the best thing since slicing a loop.

Of course, the music industry has gone through the wringer as it’s wrestled with technology enabling piracy, broadcasting, sampling, distribution and pretty much everything else in between. The effective ‘democratisation’ of anything is inherently bad for those in charge. But (bless them) they’ve got their heads around it and the industry is buzzing, with the global market growing by 7.4% in 2020, the 6th consecutive year of growth.

From an artist perspective,

it’s felt like they’re (as possibly they’ve always been) at the raw end of the deal, certainly when it comes to being paid for their work — currently netting out at somewhere around 1p for 3 streams on Spotify. And this feels a somewhat circular problem that music’s ubiquity lowers the overall value of the art itself. Because we can have it whenever we want, on demand, we value it less and artists feels the pinch.

But at the same time, the opportunity for artists to connect directly with fans has never been greater. As has the opportunity for them to galvanise and activate those fans, to build buzz and momentum around releases. The SBTV platform created by Jamal Edwards MBE was a fundamental way of building out the grime scene through the showcasing of often extremely low budget videos to a growing fanbase, launching the careers of Ed Sheeran and Stormzy.

And technology helped fan culture grow exponentially, in a way it couldn’t possibly have otherwise done so. However, the recent Joe Rogan controversy with Spotify shows that artists run the risk of having their music hosted alongside other less savoury creators, and being forced to pull their work off the platform as a result.

Fans have more meaningful ways than ever to connect with artists, from creating bedroom remixes and lip syncing on TikTok, to hosting listen parties with friends, the digital connectivity of fans powers this generation of emerging and established artists.

Yet it’s also true that the current streaming war between Spotify, Apple Music and Tidal have seen some artists being only exclusively available on certain platforms, meaning fans having to take out multiple subscriptions or miss out.

And if Snoop Dogg’s recent play with Death Row is anything to go by, we might soon need to buy NFT tracks too.

And it’s hard not to feel that the algorithm leads to fans missing out on as much music as they’re being fed — a steady stream of ‘you liked that, now like this’ doesn’t offer real music fans the chance for serendipitous discovery, the same way as rummaging around a record store did or does. And for example, did Jay-Z’s heavy involvement in Tidal result in a conflict of interest that led to a greater promotion of Roc Nation artists than others?

And finally,

as the relationship between artists and fans becomes deeper and wider, brands have a greater range of opportunities to establish a proper footprint in music, through association with, or co-creation/origination of, music-centred activities. Yet only a few brands thus far have got this right, adding to the culture, rather than getting in the way of people having a good time.

With every generational and technological shift comes those who both celebrate and criticise, and whether we’re in a utopian music moment of unlimited access to both music and artists, or a dystopian world where our listening habits are controlled by the algorithm, what is clear is that despite the tectonic shifts that have surrounded it, music remains absolutely central to our culture.

Whatever the era, music finds a way.

Featured image: Red Bull Studios New York