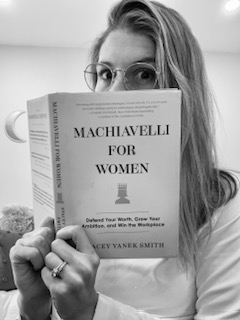

This year I discovered Machiavelli for Women by NPR Reporter, Stacey Vanek Smith. Actually my husband found it in the New York Times, and while watching me struggle with biases in the workplace, he suggested I turn toward the advice of a medieval diplomat. This was not my first foray into applying wartime strategy to my career approach, as I often called upon The Art of War by Sun Tzu in times of particular struggle. Often misunderstood as ruthless and misquoted for “the ends justify the means,” his perceived narcissism coined the personality disorder now deemed Machiavellianism. So my preconceived notions of Niccolo Machiavelli gave me pause on how women can positively gain from this seemingly barbaric male politician. If you’re not familiar, as a final effort to resume power, Machiavelli wrote The Prince as a plea to Lorenzo de’ Medici who had just taken Florence and banned Machiavelli from his adored home city for life. The Prince proved to be the greatest work of Machiavelli’s life, revealing ugly truths about human nature and the strategy to gain and maintain power.

Smith first approaches the reader with a rabble rousing account of the many forms of discrimination, injustices, and biases women face in the workforce. She carefully outlines issues in each chapter and applies modern and Machiavellian advice to combat the gender pay gap, confidence (imposter syndrome), respect, parenting biases, and more. I applaud Smith on her prowess of The Prince’s advice and the practical application drawn in parallel to women’s daily struggles, while also including supporting data and insights, as well as advice from business leaders.

One of my favorite lessons and take-aways from the book addresses how to gain equal respect in the workplace to men, particularly when up against common microaggressions like interrupting or “he-peats”(as Smith calls, when a man reiterates and claims ownership of a woman’s idea). Smith references a study that found female Supreme Court justices to be three times more likely than male justices to be interrupted by other male justices. As women, we’ve all been there, even RBG! I struggle with Smith’s solution being somewhere between kowtowing and towing the line, but she applies Machiavelli’s perspective on how a leader must be more feared than loved, and equally “inspire fear” but also “escape hate”. As Smith puts it, “In moments when a prince has to choose between doormat and dragon lady, Machiavelli comes down squarely on the side of aggro-bitch” drawing the parallel to “men are less careful how they offend him who makes himself loved, than him who makes himself feared.” Machiavelli’s advice is inspiring, but women rarely have the opportunity to exercise “aggro bitch mode” when the slightest aggression is viewed as emotional or hormonal and unfit for the workplace. As I continued reading Smith’s outline I found Machiavelli’s advice to encourage more diplomacy and shrewdness, stating things like a prince must apply “all the fierceness of lion and all the craft of the fox.”

Women and the Dark Arts

One chapter jumped out at me as it addressed something I have experienced a lot but have rarely talked about; Women and the Dark Arts. The chapter opened like the others with a quote from Machiavelli, this one reading, “The ruler is not truly wise who cannot discern evils before they develop themselves, and this a faculty given to few”. Smith continues with the hard truth that women can be just as detrimental as men to women’s advancement in the workplace by enacting hostile and gender-sabotaging micro-aggressions for their individual gain. In my personal experience I have faced countless inappropriate and undermining assaults by men, but none stung as much as the moments a fellow female coworker struck in a dubious fashion.

These female offenders can be hard to spot, often posing as an ally, so Smith assigned them five personas; The Higherland, The Queen of Hearts, MachiavelliAnnes, and Darth Mentor/Manage, along with the ways to spot and disarm them. For example, the Highlander, the cream of the crop whose ascension to the top comes with the promise to not threaten the patriarchy, thus making her the token female in power and in her mind, always a target for siege. Typically, the Highlander rose to power by ruthlessly dethroning another woman (never man, as her silent agreement is always upheld). Yikes, right!? How do you spot a Highlander? She’s hard to miss and to stomach, being outwardly mean in public settings, sucks-up to whoever is valuable to her in the most unsubtle of ways, and if she has any friends in her gender they will be equally nasty (think Mean Girls). So what’s their kryptonite? Open and calm one-on-one confrontation, oh, and make sure your allies and network is strong. These ladies thrive with an audience, so choose a one-on-one setting and the more confident and unafraid you can be the more she will be disarmed. I applied Smith’s advice when dealing with a Highlander manager, and for the short term it worked. I calmly and confidently called out her hostility towards me in a meeting and appealed to her ego, asking for constructive feedback on how to build up to one of her strengths. I knew maintaining my position of strength made me less of a target and I didn’t appear weak to my manager, so she backed-off and viewed me more as a tool to gain more power.

The pandemic has changed the script around wellness and mental health, forcing employers to see their employees as truly human. Compassion is trending and more leaders are touting how their companies value their people above all else. My LinkedIn feed is a tidal wave of emotional support for employees and colleagues, as well a stronger sense of sisterhood in tumultuous times. I’m seeing well-known “girl bosses”or “MachiavelliAnnes” are adopting new workplace and professional personas, replacing their tropes of “nice girls don’t get the corner office” with exclamations to “put the human back in human resources”. So, have the tigers really changed their stripes? Should we let down our guard and bring these women into your nooks and crannies? Let’s ask Machiavelli:

“A man who is used to acting in one way never changes; he must come to ruin when the times, in changing, no longer are in harmony with his ways.”