Ostracism was invented by the Athenians more than 2500 years ago. Lacking both fast broadband and social media, they inscribed the names of people they wanted to exclude or banish on bits of broken pottery (‘ostraka’).

It was an unfortunate precedent.

Since those days countless millions of people have suffered exclusion, jail, exile or death at the hands of their religious, political or nationalist enemies. It is estimated that Stalin, Hitler and Mao — to name but three — were responsible, directly or indirectly, for eliminating at least 60-70 million humans. But in some smaller countries — eg Bosnia, Rwanda, and the Cambodian State of Democratic Kampuchea — the devastation and death toll was equally horrendous.

Fortunately, the death toll from cancel culture in western democracies has been less dramatic! But before we celebrate that, remember that cancel culture is a relatively recent phenomenon — dating from around the start of the #MeToo movement in 2014.

Being pilloried whilst alive is a miserable experience, and the posthumous cancellation of numerous historical figures for alleged guilt or complicity, is beginning to leave large holes in the cohorts of those we used to call the great and good.

Is there another way?

Is it reasonable to ask dedicated activists to be more measured, and less precipitous in their commitment to ostracism? I believe it is. And I think it would be so much better if they took a leaf out of the book (or should I say papyrus, parchment or wax) of one of the most famous Athenians, and use Socratic Dialogue to seek the truth.

In other words, why wouldn’t a potential canceller ask questions first and encourage everyone else to ask their own questions, rather than rush to premature (and quite often incorrect) judgement?

No successful education system flourishes just by telling. A great question is worth any number of answers. If I look back to my own school days, the greatest influence on my ability to think and articulate was the Debating Society.

Here’s a quick summary of why it worked so well:

- All motions had to be formally proposed, opposed and seconded. Skills and devices like oratory and humour weren’t enough. Formal debate was built on orderly presentation of the case pro or con.

- No motion stood much of a chance without evidence, substantiation and support. Simply ranting was unacceptable.

- You couldn’t always speak to motions and causes you personally believed in. At my school you had to put the case against your own beliefs on a regular basis. I found role reversal a brilliant brain sharpener.

Here are five more reasons for favouring dialogue over diatribe, and debate over delisting:

- Writing people off for something they have thought, done, stood for, or allegedly been associated with is just so brutal. All belief systems and religions recognise the possibility of redemption as a core principle. One strike and you are out is just… well, unjust.

- We all know that humans are consistently inconsistent and fallible. Treating people as guilty without giving them the chance to prove their innocence is simply unfair.

- Refusing to provide evidence or listen to witnesses is contrary to natural justice.

- If there’s anything worse than arbitrarily condemning a fellow human being, it’s telling everyone else to ostracise, exclude or cancel them.

- And when we look at the world of ‘matter and meaning’ that MediaCat Magazine is focusing on this month (Jan 2022), do all these allegations matter? Really? And what stretch of meaning is required to make the case?

Finally let me share a quote from Wikipedia on rewriting history, which has now been dignified with the descriptor: Historical Revisionism.

“Negationism, also called denialism, is falsification or distortion of the historical record. It should not be conflated with Historical Revisionism, a broader term that extends to newly evidenced, fairly reasoned academic reinterpretations of history”.

Whoever wrote that surely qualifies as a wokeish grand master. ‘Newly evidenced’ and ‘fairly reasoned’ take the biscuit as specious justifications for outrageous backfitting. Examples are too numerous to instance, but look at the recent cancellation of Bonnie Prince Charlie for not only losing the Battle of Culloden but also ‘choosing’ to escape on board a French ship that had once carried slaves.

We have the National Trust to thank for making the connection. Their Scottish branch has also just cancelled Peter Pan author JM Barrie for having been born in a weaver’s cottage at Kirriemuir at a time when slaves (it says) wore clothes woven in Scotland. Not specifically at Kirriemuir, just in Scotland.

Editor’s note

Whilst we acknowledge David’s points about measured debate, it’s worth noting that nuance often gets lost online, particularly places like Twitter where cancel culture movements tend to form. Moreover, a lot of initially mature debate and discussion on online forums can quickly descend into argument and vitriol. It’s also worth pointing out that, sometimes, reasoned debate just doesn’t get you anywhere: something the recent Netflix film, Don’t Look Up (2021) explored.

And that there’s a difference between cancelling someone that doesn’t deserve it and cancelling someone that needs to be brought to account. With the latter, it’s often the case that the institutions and existing frameworks for calling abusive individuals to account have failed, and thus the Twitter mob arises, in an effort to seek some sort of justice. However, when this happens it’s often a divisive subject and/or individual, so the back and forth online rages on. J.K. Rowling is an ongoing example.

From a marketing point of view, here are some examples rightfully calling things out:

- UK Government’s ‘Stay home save lives’ sexist campaign

- Burger King’s ‘women belong in the kitchen’ tweet on International Women’s Day

- Snickers’ ‘you aren’t you when you’re hungry’ homophobic ad in Spain

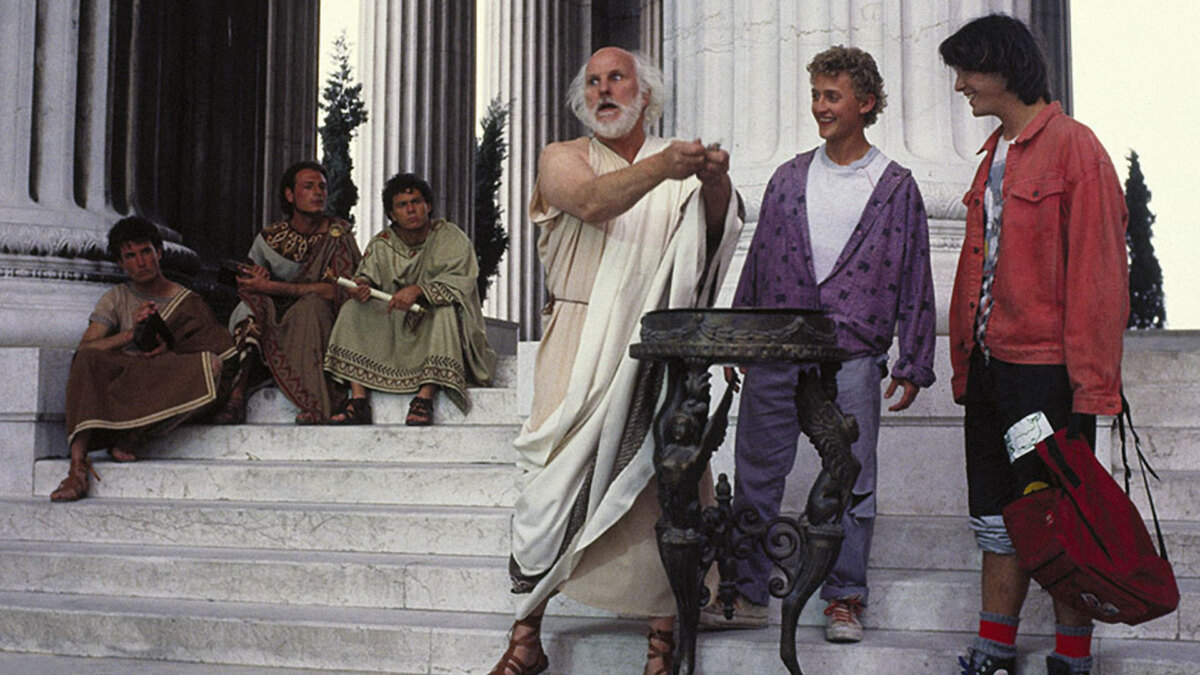

Featured image: Bill & Ted’s Excellent Adventure (1989)