Since George Lois died in November, we’ve heard a lot about the ninety-odd covers he designed for Esquire magazine in the sixties — those images (now enshrined in MoMA) of Ali as St. Sebastian, and Warhol drowning in a can of soup . We’ve heard, yet again, the story of how he threatened to kill himself by jumping from a window when a client wouldn’t buy his work, and his definition of advertising as ‘poison gas… it should bring tears to your eyes, unhinge your nervous system, and knock you out’. Fair enough, these are all key parts of the image Lois consciously built for himself throughout his life: the fist-fighting Greek kid from the Bronx, the Bad Boy of Advertising, the Counter-Cultural Artist.

Which are all part of the truth. But for a man now revered as one of the great advertising gurus, we’ve heard surprisingly little about the actual ads he made. It’s not as if these are hard to find: Lois wrote about his work repeatedly, and maintained an excellent website of everything he’d done. So I’d like to comment on some of these now, because I think George Lois is a more interesting figure than he’s often taken for. And because there are things today’s agencies could learn from his work, besides just being arrogant and contrary.

We might as well start with the MTV case, because it’s the one most people will mention if pushed to name any of Lois’s ad campaigns. MTV was the first cable channel showing nothing but music videos. Launched in 1981, it struggled because the concept was so new and none of the cable operators wanted to touch it. The problem was not that the public didn’t want it, it was that they couldn’t get it.

Lois came up with a line: ‘I Want my MTV’. Well, actually he adapted a line that he had used successfully many years previously for a breakfast cereal — ‘I want my Maypo’ — absurdly uttered in a series of commercials by top baseball stars, crying like children. In a TV campaign he now urged the public to ring their cable operators and shout ‘I want my MTV’ — but the campaign only took off when Lois called Mick Jagger and asked him to do it too. When Jagger agreed, it made headlines, other rock stars wanted to follow suit, and the whole thing became a phenomenon. (When Sting sings the words at the end of Dire Straits’ ‘Money for Nothing’, to the tune of ‘Don’t Stand So Close to Me’, everyone is paying tribute to the way the campaign had by then entered the language.)

There are three things here that reflect the kind of work Lois valued and did best.

First, it depends on a slogan

Lois loved slogans. He wrote a whole chapter called ‘You Gotta Have a Slogan’. For Cutty Sark, he popularised ‘Don’t Give Up the Ship’; for Braniff Airlines, he created ‘If you’ve got it, flaunt it’ – another phrase that passed into the language.

Second, it makes highly effective use of celebrities

Lois really loved celebrities; he wrote a whole book called $ellebrity, and for the Braniff Airlines campaign he set up unexpected conversation pieces yoking Andy Warhol with Sonny Liston, Marianne Moore with Mickey Spillane. When he asked Bob Dylan to write a song about the wrongly convicted Rubin ‘Hurricane’ Carter, Dylan responded not just with the song but by putting on two whole fundraising concerts for the cause. (And of course, celebrities featured in many of those Esquire covers.)

Third, it’s perhaps less an ad, more a highly effective piece of PR

Lois had a real talent for doing things at minimal cost that would create a huge media furore; there’s much about him that evokes comparison with P.T. Barnum. Like the Great Showman, he understood the central importance of fame and how to create it: one of his proudest boasts was how he had made Tommy Hilfiger famous overnight with a single ad.

And both knew how to create news not just for their clients, but for themselves. When Lois came out with that ‘poison gas’ line on live TV it drew a rash of newspaper headlines the next day, just as he’d meant it to (‘I suppose the phrase is probably excessive’ he later wrote, in one of the many books which, like Barnum, he published throughout his career).

In 1967 Lois was asked to advertise a brand of synthetic leather called Naugahyde

He imagined and designed a creature called the Nauga — he’s ugly, but rather charming, and perhaps not coincidentally, anticipates the characters from Pixar’s Monsters, Inc (2001). Unlike other animals, it was said, the Nauga could shed its hide without any harm to itself.

In the Nauga, Lois created what today we might call a powerful distinctive asset. Or, as he put it: ‘Great advertising should have a memorable visual image, a kind of graphic mnemonic’. Lois’ original training was as a graphic designer, and throughout his career he probably created more logos than ad campaigns (his revision of the MTV logo was also an important part of that campaign’s success). The Nauga was a lot of fun, children loved it, and it lent itself well to in-store displays, merchandise, promotional items, and so on. It ran for years and ensured that Naugahyde dominated what could easily have become a commodity category.

The Nauga also reminds us how much Lois appreciated the power of humour and charm:

…a creative person who is humourless could never produce consistently great work in communicating with warmth and humanity to the vast majority of the populace.

For all the bad boy antics, Lois was a man of moral principle. His one marriage stayed rock solid for seventy years, and he vituperated against the boozing and womanising depicted in Mad Men (though he also happily leaned on the series to boost his own fame, boasting that he was better looking than Don Draper).

He stood for women’s rights, and two of the three professional mentors he acknowledged were women. He did much to fight against racism, and his support for Rubin Carter lost him the Cutty Sark account.

Yet he never lost sight of the commercial purpose of most advertising:

… a great commercial or print advertisement should say, in-your-face, that this is a commercial message and that we’re asking for the sale — not by pounding your head with a hammer, but by charming your ass off.

But I buy at Alexander’s!

Another campaign that charmed the ass off the people of New York was the one he did in 1980 for a struggling department store chain called Alexander’s. A woman struts the streets of midtown Manhattan, singing as she goes that:

I browse at Bloomingdale’s,

I breakfast at Tiffany’s,

But I buy at Alexanders!

Lois had to fight lawyers all the way who were terrified of mentioning competitors by name, then he compounded the risk by filming scenes outside all the actual stores. It became one of the most talked about campaigns in New York, and is still fondly remembered forty years later. (Sadly, the store itself went out of business in 1992 anyway. Ads can’t solve all your problems.)

George Lois could do cool and witty

He started at DDB, after all — as a campaign like Wolfschmidt’s Vodka demonstrates. But the Alexander’s campaign is none of this, it’s flamboyant, shamelessly commercial, even camp. It shows he was as happy to build a campaign around a jingle as around a slogan, because his goal was to create work that was above all popular and talked about:

If your advertising doesn’t have the power to become a topic of conversation for everyone in the nation, you forfeit the chance for it to be famous.

Given this ambition, it is rather sad that of the many campaigns Lois created — he was still working at the coal face of advertising until his final years — there are hardly any for major national, let alone global, brands. Fake leather and a third-tier local department store were about as good as it got — though that never repressed his enthusiasm or love for what he did.

At the end of the day, the biggest brand Lois created was probably his own. That doesn’t mean we shouldn’t respect his advertising achievements, or that we have nothing to learn from them.

Lois was a showman at heart

He had a knack for creating fame. He knew the importance of charm and humour. He was plugged into popular culture, and used celebrities cleverly and effectively. He valued slogans, visual images such as logos and characters, and jingles.

In other words, he did a lot of things, and had a lot of beliefs, that seem somewhat out of fashion in today’s advertising industry.

So when I read about creative directors of top agencies saying how much they admire the timeless works of George Lois, I hope I am right to be encouraged. Because what they can learn from him is not just how to be obnoxious or intransigent — though I don’t think he was either of those things as much as he pretended — but how to make a brand famous, how to create enduring brand properties, and how to charm and excite the public through bravado, cheek, and fun.

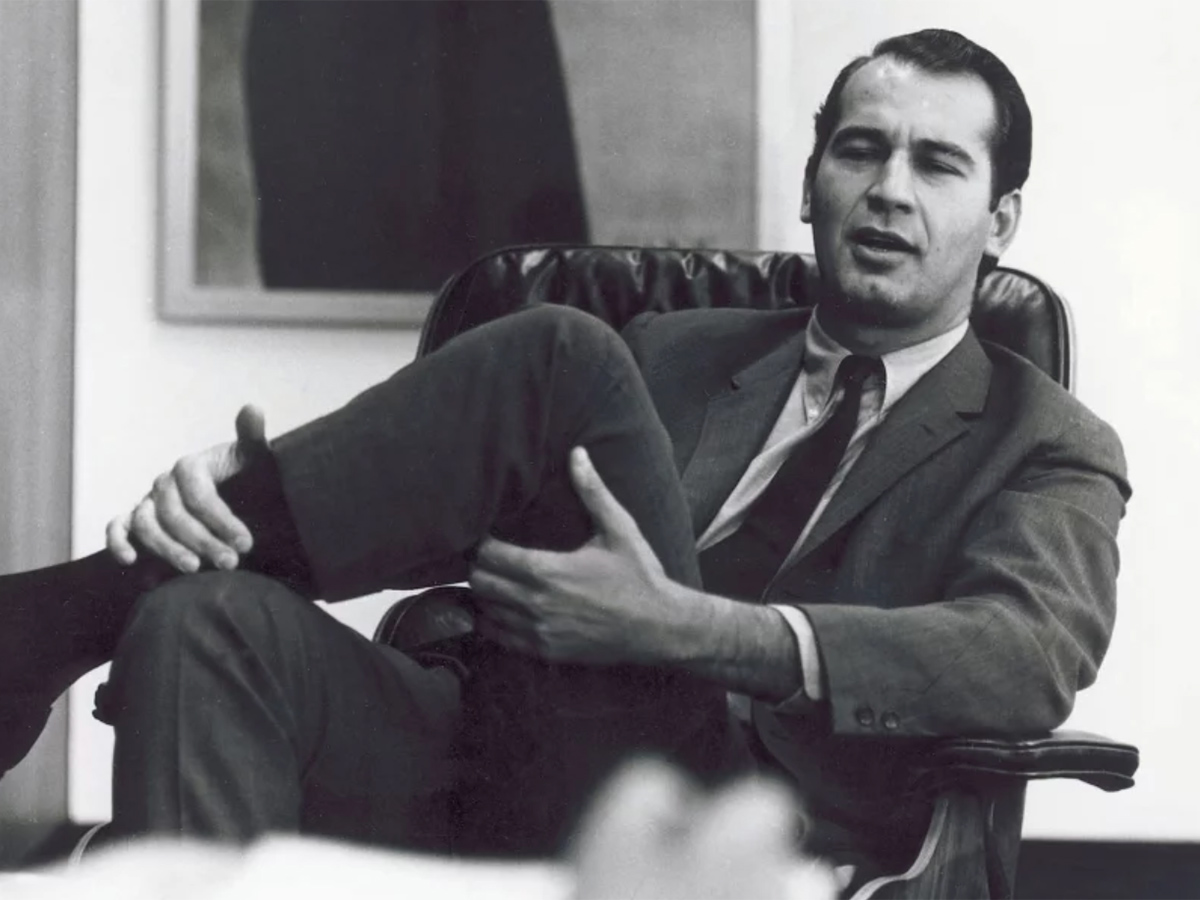

Featured image: Phaidon Press